The first decade of the 21st century witnessed a significant number of high-impact environmental catastrophes. These events included powerful earthquakes, devastating tsunamis, intense hurricanes, widespread droughts, and extensive wildfires, impacting populations globally and resulting in substantial economic losses and humanitarian crises.

Studying this period provides valuable insights into disaster preparedness and response strategies. Analysis of these events informs scientific understanding of geological and meteorological processes, leading to improved predictive models and early warning systems. Furthermore, examining the socio-economic consequences of these catastrophes helps shape policies for disaster mitigation and sustainable development. The lessons learned from this era are crucial for building resilience in communities facing similar threats in the future.

This article will explore specific examples of major natural disasters from this period, examining their causes, impacts, and the responses they elicited. It will also analyze the evolving approaches to disaster management and highlight the ongoing need for international cooperation and proactive measures to mitigate the effects of future events.

Disaster Preparedness Tips Informed by the 2000s

Experiences from significant natural disasters during the 2000s offer invaluable lessons in preparedness. These tips, derived from past events, aim to improve individual and community resilience in the face of future threats.

Tip 1: Develop an Emergency Plan: Establish a comprehensive family emergency plan, including communication strategies, evacuation routes, and designated meeting points. The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami underscored the critical need for clear communication protocols during large-scale emergencies.

Tip 2: Assemble an Emergency Kit: Prepare a well-stocked kit containing essential supplies like water, non-perishable food, first-aid supplies, a flashlight, and a battery-powered radio. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 highlighted the importance of self-sufficiency in the immediate aftermath of a disaster.

Tip 3: Understand Local Risks: Research the specific natural hazards prevalent in one’s region. Understanding regional vulnerabilities, such as those to earthquakes as seen in the 2003 Bam earthquake, is crucial for effective preparation.

Tip 4: Secure Property and Belongings: Take preventative measures to protect homes and possessions from damage. The widespread destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina demonstrated the importance of reinforcing structures and securing valuable items.

Tip 5: Stay Informed: Monitor weather reports and official alerts from local authorities. Early warning systems, as implemented following the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, can provide crucial time for evacuation and preparation.

Tip 6: Support Community Preparedness Initiatives: Participate in community-level disaster preparedness programs and drills. Community-based responses, as observed after the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, are often vital in the initial stages of a disaster.

Tip 7: Consider Insurance Coverage: Evaluate insurance policies to ensure adequate coverage for potential disaster-related losses. The extensive economic damage caused by events like Hurricane Katrina underscored the importance of financial preparedness.

Proactive planning based on lessons learned from past disasters significantly enhances resilience and reduces vulnerability. These steps can contribute to increased individual and community safety, minimizing the impact of future catastrophic events.

These preparedness tips lead to the concluding discussion on the importance of ongoing research and international collaboration in disaster risk reduction.

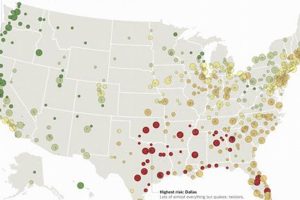

1. Geographic Distribution

Analysis of natural disaster occurrences during the 2000s reveals distinct geographic patterns. Certain regions exhibited heightened vulnerability to specific types of disasters. Coastal areas, particularly those bordering the Pacific and Indian Oceans, experienced a disproportionate share of tsunamis and cyclones. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami tragically demonstrated this vulnerability, impacting numerous countries across a vast geographic area. Similarly, regions situated along major fault lines, such as those in parts of Asia and the Americas, were prone to significant seismic activity. The 2003 Bam earthquake in Iran and the 2005 Kashmir earthquake underscore this geological influence on disaster distribution. Understanding these geographic predispositions is crucial for targeted disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies.

Furthermore, geographic distribution influences the types and severity of impacts experienced. Low-lying coastal regions face increased risks from storm surges and flooding, as witnessed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Densely populated areas, regardless of their geographic location, often experience more severe humanitarian consequences due to the sheer number of people affected, exemplified by the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Accessibility and infrastructure also play a significant role; remote or underdeveloped regions often face greater challenges in post-disaster recovery, as highlighted by the aftermath of the 2005 Kashmir earthquake. Examining the interplay of geographic factors with social and infrastructural elements provides a more comprehensive understanding of disaster impacts.

In conclusion, geographic distribution plays a pivotal role in understanding the complexities of natural disasters. Mapping historical events and analyzing regional vulnerabilities allows for more effective allocation of resources, development of targeted early warning systems, and implementation of appropriate building codes and land-use planning. This geographic perspective is essential for minimizing human and economic losses in the face of future events. Continued research into the interplay of geographic factors with disaster occurrence and impact remains critical for enhancing global disaster resilience.

2. Economic Impact

Natural disasters of the 2000s exacted a substantial economic toll globally. Analyzing these costs is crucial for understanding the full impact of these events and for developing effective strategies for mitigation and recovery. Economic consequences extend beyond immediate damages, affecting long-term development trajectories and necessitating significant financial investments in reconstruction and rehabilitation.

- Direct Costs

Direct costs encompass the immediate physical damage to infrastructure, property, and agricultural lands. The 2005 Hurricane Katrina, for example, resulted in massive destruction along the US Gulf Coast, causing unprecedented insured losses. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami similarly devastated coastal communities across multiple countries, leading to extensive damage to housing, businesses, and critical infrastructure. These direct costs often necessitate significant public and private sector spending for rebuilding and recovery efforts.

- Indirect Costs

Indirect costs encompass the wider economic repercussions of a disaster, including business interruptions, supply chain disruptions, and reduced tourism revenue. The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, for instance, significantly disrupted global supply chains in the automotive and electronics industries. Disruptions to transportation networks and trade flows can have cascading effects on regional and global economies. These indirect costs are often more challenging to quantify but are crucial for understanding the full economic impact of a disaster.

- Long-Term Economic Impacts

Long-term economic impacts include reduced economic growth, increased poverty, and long-term health care costs. The 2010 Haiti earthquake, for example, significantly hampered the country’s long-term development prospects, exacerbating existing poverty and inequality. Disasters can also lead to displacement of populations and disruption of livelihoods, impacting economic productivity for years to come. Understanding these long-term consequences is crucial for developing sustainable recovery strategies.

- Impact on Insurance and Financial Markets

The economic fallout from major disasters often has significant implications for insurance and financial markets. The substantial insured losses from events like Hurricane Katrina led to increased insurance premiums and greater scrutiny of risk assessment models. Disasters can also impact investor confidence and market stability, as seen in the aftermath of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. These events underscore the need for robust financial instruments and risk transfer mechanisms to manage the economic consequences of disasters effectively.

Analyzing the economic impacts of 2000s natural disasters provides valuable insights into the financial vulnerabilities of various sectors and regions. This understanding informs policy decisions related to disaster risk reduction, insurance regulations, and investment in resilient infrastructure. By studying these past events, governments, businesses, and communities can better prepare for and mitigate the economic consequences of future disasters.

3. Humanitarian Crises

Natural disasters of the 2000s frequently precipitated large-scale humanitarian crises, posing significant challenges to relief efforts and highlighting the vulnerability of populations worldwide. Understanding the complexities of these crises is essential for improving disaster preparedness, response mechanisms, and long-term recovery strategies.

- Displacement and Migration

Disasters often resulted in massive displacement of populations, creating significant needs for shelter, food, water, and medical assistance. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami displaced millions across several countries, while Hurricane Katrina in 2005 led to widespread displacement along the US Gulf Coast. These events demonstrated the logistical complexities of managing large-scale evacuations and providing adequate support for displaced populations. Displacement can also lead to long-term social and economic disruption, requiring extensive efforts for resettlement and community rebuilding.

- Public Health Impacts

Natural disasters can severely impact public health infrastructure and create conditions conducive to the spread of infectious diseases. The 2010 Haiti earthquake devastated the country’s already fragile healthcare system, leading to shortages of medical supplies, personnel, and facilities. Disruptions to sanitation systems and access to clean water following disasters like the 2005 Kashmir earthquake increase the risk of waterborne illnesses. Addressing public health needs in the aftermath of a disaster requires rapid deployment of medical resources and implementation of disease prevention measures.

- Food Security Challenges

Disasters can disrupt agricultural production, damage food storage facilities, and disrupt transportation networks, leading to food shortages and malnutrition. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami significantly impacted fishing communities and agricultural lands, leading to widespread food insecurity. Droughts, such as the severe drought in the Horn of Africa in the early 2000s, can also trigger humanitarian crises characterized by widespread famine and displacement. Ensuring access to food aid and supporting the restoration of local food production are crucial elements of disaster response.

- Protection of Vulnerable Populations

Certain groups, such as children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and marginalized communities, are particularly vulnerable during and after natural disasters. The 2005 Kashmir earthquake disproportionately impacted remote and mountainous communities, highlighting the challenges of reaching vulnerable populations with aid. Protecting these groups requires targeted assistance programs, ensuring access to essential services, and addressing specific needs, such as psychosocial support and protection from exploitation and abuse.

The humanitarian crises stemming from 2000s natural disasters underscored the need for effective international cooperation, coordinated relief efforts, and investment in disaster risk reduction measures. Analyzing these past events provides valuable lessons for strengthening humanitarian response mechanisms, improving the protection of vulnerable populations, and building more resilient communities in the face of future disasters.

4. Scientific Advancements

The 2000s witnessed significant scientific advancements directly influenced by the occurrence and impact of major natural disasters. These advancements, spanning various disciplines, have enhanced understanding of Earth processes, improved predictive capabilities, and informed the development of more effective disaster mitigation and response strategies. Examining these developments is crucial for highlighting the ongoing interplay between scientific progress and disaster management.

- Improved Early Warning Systems

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami tragically highlighted the need for robust tsunami early warning systems. Subsequent investments in oceanographic monitoring, data analysis, and communication infrastructure led to the establishment of comprehensive tsunami warning networks, particularly in the Indian and Pacific Ocean regions. These systems, incorporating real-time data from buoys and seismic sensors, provide crucial minutes to hours of advance warning, enabling timely evacuations and potentially saving lives in future events. The efficacy of these systems has been demonstrated in subsequent tsunami events, though challenges remain in ensuring effective communication and community response.

- Enhanced Earthquake Engineering

The devastating impacts of earthquakes like the 2003 Bam earthquake and the 2005 Kashmir earthquake spurred advancements in earthquake engineering and building codes. Research into ground motion, structural behavior, and building materials led to the development of more resilient construction techniques and stricter building regulations in earthquake-prone regions. These advancements aim to minimize structural damage and reduce casualties during future seismic events. However, widespread implementation and enforcement of these codes remain a challenge, particularly in developing countries.

- Advanced Weather Forecasting

The increasing frequency and intensity of hurricanes and cyclones during the 2000s drove advancements in meteorological modeling and weather forecasting. Improved satellite technology, data assimilation techniques, and computational power have enhanced the accuracy and lead time of hurricane track and intensity forecasts. This progress enables more effective planning for evacuations, resource allocation, and emergency response. However, predicting the precise impacts of these storms, particularly rainfall and storm surge, remains an area of ongoing research.

- Remote Sensing and Disaster Monitoring

The use of remote sensing technologies, including satellite imagery and aerial photography, became increasingly sophisticated during the 2000s, providing valuable data for disaster monitoring and damage assessment. Following events like Hurricane Katrina, remote sensing data was instrumental in mapping flooded areas, assessing infrastructure damage, and guiding search and rescue operations. This technology also plays a crucial role in monitoring volcanic activity, tracking wildfires, and assessing the impacts of droughts. Continued development of remote sensing technologies holds significant promise for improving disaster response and recovery efforts.

These scientific advancements, spurred by the challenges posed by 2000s natural disasters, have significantly enhanced our ability to understand, predict, and respond to these events. Continued investment in research and development, coupled with effective implementation of these advancements, is essential for minimizing the human and economic costs of future disasters. Integrating scientific knowledge with policy decisions and community-level preparedness efforts is crucial for building more disaster-resilient societies.

5. Disaster Management

The frequency and intensity of natural disasters throughout the 2000s significantly shaped the evolution of disaster management theory and practice. Experiences from events like the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and the 2010 Haiti earthquake exposed critical gaps in existing disaster management frameworks and underscored the need for more comprehensive and proactive approaches. This period emphasized a shift from reactive, post-disaster relief efforts towards a more proactive, risk-reduction approach encompassing preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery.

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, for instance, highlighted the critical importance of early warning systems and international coordination in disaster response. The scale of the disaster overwhelmed the capacity of individual nations, demonstrating the need for collaborative international assistance mechanisms. Hurricane Katrina exposed vulnerabilities in local and national emergency preparedness within developed countries, emphasizing the importance of community resilience, effective communication, and pre-positioned resources. The 2010 Haiti earthquake further underscored the challenges of coordinating aid and providing essential services in resource-constrained environments, highlighting the need for capacity building and strengthening local institutions.

These experiences led to significant advancements in disaster management practices. The development of comprehensive national disaster management plans, incorporating risk assessments, vulnerability mapping, and community engagement, became increasingly common. Emphasis on pre-disaster mitigation measures, such as building codes, land-use planning, and early warning systems, gained prominence. The importance of integrating scientific knowledge into disaster management decision-making became increasingly evident, leading to greater collaboration between scientists, policymakers, and practitioners. Furthermore, the 2000s saw a growing recognition of the crucial role of local communities in disaster preparedness and response, leading to increased emphasis on community-based disaster risk reduction strategies. While significant progress has been made, challenges remain in translating lessons learned into effective policies and practices, particularly in addressing the needs of vulnerable populations and ensuring adequate funding for disaster risk reduction initiatives.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding natural disasters occurring during the 2000s, aiming to provide concise and informative responses.

Question 1: What defines a natural disaster?

A natural disaster is a major adverse event resulting from natural processes of the Earth; examples include earthquakes, floods, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and droughts. The impact often includes significant human losses, economic damage, and disruption to societal function.

Question 2: Were the number of natural disasters in the 2000s unusually high?

While data indicates an apparent increase in the number of reported disasters, this can be partly attributed to improved monitoring and reporting mechanisms. Further research is needed to determine the extent to which observed increases reflect actual changes in disaster frequency versus improved documentation.

Question 3: What role did climate change play in 2000s natural disasters?

The influence of climate change on individual disaster events is complex. Scientific evidence suggests climate change may exacerbate certain types of disasters, such as hurricanes and droughts, by altering atmospheric and oceanic conditions. However, attributing specific events solely to climate change remains a scientific challenge.

Question 4: How did disaster management evolve during the 2000s?

The 2000s saw a shift from reactive disaster response towards proactive risk reduction strategies. Experiences from major disasters led to greater emphasis on preparedness, mitigation, community resilience, and the integration of scientific knowledge into disaster management practices.

Question 5: What were the most significant humanitarian impacts of 2000s natural disasters?

Major disasters during this period resulted in significant humanitarian consequences, including widespread displacement, public health crises, food insecurity, and the heightened vulnerability of marginalized communities. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2010 Haiti earthquake exemplify the devastating humanitarian impacts of such events.

Question 6: What lessons were learned from the natural disasters of the 2000s?

Key lessons include the importance of early warning systems, community-based disaster preparedness, resilient infrastructure, international cooperation, and the integration of scientific understanding into disaster risk reduction strategies. These lessons continue to inform disaster management practices globally.

Understanding the causes, impacts, and responses to past disasters is crucial for building more resilient communities and minimizing future losses. Continued research, investment in preparedness measures, and effective international cooperation are essential for mitigating the risks posed by natural hazards.

Further exploration of specific case studies from this period can provide deeper insights into the complexities of disaster management and the evolving strategies for mitigating risks.

Conclusion

Examination of natural disasters occurring during the 2000s reveals critical insights into the complex interplay of environmental forces, human vulnerability, and societal response. This period, marked by high-impact events such as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and the 2010 Haiti earthquake, underscored the urgent need for enhanced disaster preparedness, mitigation, and response mechanisms. Analysis of these events spurred advancements in scientific understanding, leading to improved early warning systems, enhanced building codes, and more sophisticated disaster monitoring technologies. Furthermore, the humanitarian crises resulting from these disasters highlighted the importance of international cooperation, community resilience, and the protection of vulnerable populations.

The legacy of the 2000s natural disasters serves as a stark reminder of the persistent threat posed by natural hazards. Continued investment in disaster risk reduction, informed by scientific advancements and lessons learned from past events, remains crucial for building more resilient societies. Promoting international collaboration, empowering local communities, and integrating disaster preparedness into sustainable development strategies are essential steps towards mitigating the human and economic costs of future disasters and fostering a safer, more sustainable future for all.