Catastrophic events, both natural and human-induced, have profoundly shaped civilizations throughout time. Examples include widespread pandemics, devastating earthquakes, volcanic eruptions that alter climates, and large-scale industrial accidents. These events often result in significant loss of life, widespread destruction of infrastructure, and long-lasting social and economic disruption.

Studying these impactful events provides invaluable insights into human resilience, societal vulnerability, and the complex interplay between human activity and the natural world. Analysis of past catastrophes informs disaster preparedness strategies, infrastructure development, and policy decisions aimed at mitigating future risks. Understanding the historical context of such events offers crucial perspectives on human progress, societal adaptation, and the development of strategies for survival and recovery.

This article will delve into specific examples of historically significant disasters, exploring their causes, consequences, and the lessons learned. It will also examine the evolving approaches to disaster management and the ongoing efforts to mitigate the impact of future catastrophic events.

Lessons from Catastrophic Events

Examining significant historical disasters offers valuable insights applicable to present-day challenges and future planning. These lessons span disaster preparedness, community resilience, and long-term recovery strategies.

Tip 1: Diversify Resources and Infrastructure. Over-reliance on single sources of essential resources or infrastructure creates vulnerability. The Irish Potato Famine exemplifies the dangers of dependence on a single crop. Diversification strengthens resilience against localized failures.

Tip 2: Prioritize Early Warning Systems. Effective disaster response hinges on timely warnings. The 1900 Galveston Hurricane highlighted the devastating consequences of inadequate communication. Investment in robust early warning systems is crucial for minimizing casualties and property damage.

Tip 3: Develop Comprehensive Disaster Preparedness Plans. Planning must encompass evacuation procedures, resource allocation, and post-disaster recovery efforts. The chaotic aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake underscored the necessity of well-defined plans.

Tip 4: Foster Community Engagement and Education. Informed and prepared communities are better equipped to respond to disasters. Public awareness campaigns and community drills play a crucial role in enhancing resilience.

Tip 5: Preserve Historical Records and Documentation. Detailed records of past events provide invaluable data for future analysis and planning. Studying historical accounts of disasters like the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 informs modern building codes and urban planning.

Tip 6: Invest in Research and Technological Advancements. Scientific understanding of natural hazards and technological advancements in mitigation strategies are critical. The development of earthquake-resistant building technologies exemplifies the importance of ongoing research.

Tip 7: Promote International Cooperation and Information Sharing. Global collaboration is essential for addressing transboundary disasters and sharing best practices in disaster management. The Chernobyl disaster highlighted the need for international cooperation in nuclear safety and disaster response.

Learning from past catastrophes empowers communities and nations to enhance preparedness, mitigate risks, and build more resilient futures. These lessons contribute to a proactive approach to disaster management, minimizing the impact of future catastrophic events.

By integrating these lessons into policy and practice, societies can strive toward a more secure and sustainable future, better prepared to navigate the challenges posed by both natural and human-induced disasters.

1. Scale of Destruction

The scale of destruction serves as a critical defining characteristic of major historical disasters. It encompasses the magnitude of physical damage, the geographic extent of the affected area, and the disruption to both natural and built environments. This destruction often results from a complex interplay of factors, including the intensity of the initiating event (e.g., earthquake magnitude, hurricane wind speed), the vulnerability of the affected area (e.g., building codes, population density), and the efficacy of pre- and post-disaster mitigation measures. The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, for instance, generated tsunamis that devastated coastal regions thousands of kilometers away, demonstrating the potential for widespread impact even from a geographically localized event. Conversely, the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, while significantly less powerful in terms of energy released, caused disproportionate damage due to the city’s geological characteristics and building practices. Understanding the factors contributing to the scale of destruction is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies.

Analyzing the scale of destruction provides insights into the complex relationship between human societies and their environment. The impact on infrastructure, including transportation networks, communication systems, and essential services like water and power supply, directly influences the immediate and long-term consequences of a disaster. The destruction of agricultural land, forests, and other natural resources can lead to food shortages, economic hardship, and ecological disruption. The scale of damage to the built environment, including homes, businesses, and cultural heritage sites, influences recovery efforts and can have lasting social and psychological impacts. The 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, which devastated Tokyo and Yokohama, exemplifies the multifaceted nature of destruction in densely populated areas, highlighting the interplay between physical damage, societal vulnerability, and long-term recovery challenges.

Assessing the scale of destruction is essential for effective disaster response and long-term recovery planning. Accurate assessments inform resource allocation, prioritize aid distribution, and guide the development of rebuilding strategies. Understanding the extent of damage also allows for more accurate estimations of economic losses, which are crucial for insurance claims, government assistance programs, and long-term economic recovery planning. Furthermore, studying the scale of past disasters provides valuable data for improving building codes, land-use planning, and disaster preparedness strategies. By analyzing the interplay between the initiating event, the vulnerability of the affected area, and the effectiveness of mitigation measures, societies can work towards minimizing the scale of destruction in future disasters and building more resilient communities.

2. Loss of Human Life

Loss of human life represents a central and tragic aspect of major historical disasters. The sheer number of casualties often defines the scale and impact of these events, influencing societal responses and shaping collective memory. Analyzing mortality rates and demographic patterns within disaster contexts reveals crucial information about societal vulnerabilities and the efficacy of mitigation strategies. Events like the Black Death, which decimated populations across Europe, demonstrate the profound societal impact of widespread mortality, leading to social, economic, and cultural upheaval. Similarly, the 1918 influenza pandemic, with its devastating global reach, underscored the interconnectedness of human populations and the rapid spread of infectious diseases. Understanding the factors contributing to high mortality rates is crucial for developing effective public health interventions and disaster preparedness plans.

Examining the causes of death in historical disasters provides crucial insights into the specific risks associated with different types of events. Earthquakes, for instance, often result in deaths from building collapse and ensuing fires, while tsunamis cause drowning and trauma from debris impact. Famines, on the other hand, lead to deaths from starvation and related diseases. Understanding these specific causes informs the development of targeted mitigation measures. The Bhopal gas tragedy of 1984, for example, highlighted the dangers of industrial accidents and the need for stringent safety regulations. The Chernobyl disaster further emphasized the long-term health consequences of radiation exposure, influencing policies on nuclear safety and disaster response. Analyzing mortality patterns based on age, gender, socioeconomic status, and other demographic factors sheds light on the disproportionate impact of disasters on vulnerable populations.

The loss of human life in historical disasters serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of human existence and the importance of disaster preparedness and mitigation. Studying these events fosters a deeper understanding of the social, economic, and psychological impacts of large-scale mortality, contributing to more informed policy decisions and community-level preparedness strategies. While the scale of loss in past events can be overwhelming, analyzing the factors contributing to mortality provides valuable lessons for minimizing future risks and building more resilient societies. By understanding the specific causes of death and the vulnerabilities of different populations, efforts can be focused on developing more effective mitigation measures, improving disaster response strategies, and ultimately, reducing the human cost of future catastrophic events.

3. Social disruption

Social disruption constitutes a significant consequence of major historical disasters, often exceeding the immediate physical damage in its long-term impact. These events disrupt established social structures, norms, and routines, leading to displacement, resource scarcity, and psychological trauma. The breakdown of social order can manifest in various forms, including looting, violence, and the erosion of trust in institutions. Understanding the dynamics of social disruption is essential for effective disaster management and long-term recovery planning. The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, for instance, demonstrated the profound social consequences of widespread displacement, infrastructure collapse, and the breakdown of law and order. Similarly, the Chernobyl disaster led to the forced evacuation of entire communities, resulting in long-term social and psychological impacts.

Analyzing the social consequences of historical disasters provides insights into the complex interplay between individual experiences, community responses, and institutional capacity. Disasters often exacerbate existing social inequalities, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations. Loss of livelihoods, displacement, and disruption of access to essential services can lead to increased poverty, social unrest, and psychological distress. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, for example, had a profound impact on social hierarchies and political structures, influencing Enlightenment-era thinking on the nature of disaster and human suffering. The social disruption following the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake in Japan highlighted the challenges of rebuilding social cohesion and trust in the aftermath of widespread devastation.

Addressing social disruption requires a multi-faceted approach that considers both immediate needs and long-term recovery goals. Providing essential resources like food, shelter, and medical care is crucial in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. Restoring infrastructure, supporting economic recovery, and addressing psychological trauma are essential for long-term social healing. Furthermore, fostering community engagement and participation in recovery efforts can help rebuild social cohesion and promote resilience. Learning from historical examples of social disruption provides valuable lessons for developing effective disaster management strategies that address both the physical and social dimensions of catastrophic events, ultimately contributing to more resilient and equitable societies.

4. Economic Impact

Economic impact represents a significant dimension of major historical disasters, often extending far beyond the immediate costs of physical damage. These events disrupt economic activity, destroy infrastructure, and displace workforces, leading to both short-term and long-term consequences. The scale of economic impact depends on factors such as the magnitude of the disaster, the affected region’s economic structure, and the effectiveness of pre- and post-disaster mitigation measures. The 1929 Great Depression, while not a singular disaster event, illustrates the cascading economic effects of widespread financial instability, highlighting the interconnectedness of global markets and the vulnerability of national economies. Similarly, the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan demonstrated the significant economic disruption caused by the combined effects of natural disaster and technological failure, particularly the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.

Analyzing the economic consequences of historical disasters reveals complex interactions between direct losses, indirect costs, and long-term recovery challenges. Direct losses include damage to infrastructure, property, and agricultural land. Indirect costs encompass business interruption, supply chain disruptions, and decreased productivity. The long-term economic impact can involve reduced investment, population decline, and persistent economic hardship. The 1889 Johnstown Flood, for example, devastated a key industrial region in the United States, demonstrating the economic vulnerability of concentrated industrial activity. The Irish Potato Famine of the mid-19th century highlights the economic and social consequences of widespread crop failure, leading to mass starvation, migration, and long-term economic decline.

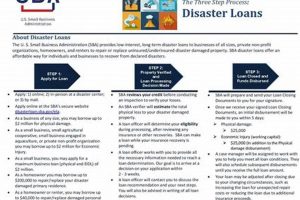

Understanding the economic impact of historical disasters informs policy decisions related to disaster preparedness, mitigation, and economic recovery. Investing in resilient infrastructure, developing robust insurance mechanisms, and promoting economic diversification can mitigate the economic vulnerability of regions prone to disasters. Effective disaster response strategies that prioritize restoring essential services and supporting businesses contribute to faster economic recovery. Learning from past economic crises and incorporating these lessons into policy and planning strengthens economic resilience and mitigates the long-term economic consequences of future catastrophic events.

5. Environmental Consequences

Environmental consequences represent a significant dimension of major historical disasters, often extending far beyond the immediate impact on human populations and infrastructure. These events can trigger profound ecological changes, affecting air and water quality, biodiversity, and ecosystem stability. The scale and duration of environmental impacts depend on factors such as the nature of the disaster, the affected ecosystem’s resilience, and the effectiveness of post-disaster mitigation and remediation efforts. The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, for instance, injected massive amounts of volcanic ash and gases into the atmosphere, affecting global climate patterns for several years. The Chernobyl disaster released radioactive materials into the environment, contaminating vast areas and causing long-term ecological damage. Understanding the environmental consequences of historical disasters provides crucial insights into the complex interplay between human activities, natural hazards, and ecosystem health.

Analyzing the environmental impacts of historical disasters reveals a complex web of cause-and-effect relationships. Earthquakes can trigger landslides, tsunamis, and soil liquefaction, altering landscapes and disrupting ecosystems. Volcanic eruptions release greenhouse gases and particulate matter, impacting air quality and potentially influencing global climate. Industrial accidents, such as the Bhopal gas tragedy, can contaminate soil and water, posing long-term risks to human health and the environment. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 demonstrated the devastating impact of large-scale oil spills on marine ecosystems, highlighting the challenges of environmental remediation. Studying these environmental consequences informs the development of more sustainable practices and effective mitigation strategies.

Understanding the environmental consequences of historical disasters is crucial for promoting environmental sustainability and building more resilient societies. Analyzing past events provides valuable lessons for mitigating environmental risks associated with human activities, developing effective environmental remediation strategies, and promoting ecosystem recovery. The Aral Sea disaster, resulting from large-scale irrigation projects, highlights the unintended environmental consequences of human interventions in natural systems. By studying these examples, societies can develop more sustainable practices that minimize environmental damage and promote ecological health. Integrating environmental considerations into disaster preparedness, response, and recovery planning contributes to a more holistic approach to disaster management, recognizing the interconnectedness between human societies and the natural environment.

6. Long-term Effects

Long-term effects constitute a crucial aspect of understanding the full impact of major historical disasters. These effects extend far beyond the immediate aftermath, shaping societal development, influencing policy decisions, and leaving lasting imprints on collective memory. Analyzing long-term effects requires considering the complex interplay of physical, social, economic, and environmental factors. The consequences of events like the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, for instance, extend beyond the immediate devastation to include long-term health issues related to radiation exposure, intergenerational trauma, and profound geopolitical shifts. Similarly, the Chernobyl disaster continues to exert long-term effects on the environment, human health, and public perception of nuclear energy. Understanding these enduring consequences provides crucial insights into the multifaceted nature of disasters and the challenges of long-term recovery.

Examining the long-term effects of historical disasters reveals the intricate ways in which these events reshape societies and influence future trajectories. Economic hardship, social disruption, and psychological trauma can persist for generations, impacting community development and individual well-being. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s, for example, led to widespread agricultural losses, economic hardship, and mass migration, shaping the social and economic landscape of the affected regions for decades. The long-term effects of the Holocaust, including the displacement of populations, the destruction of cultural heritage, and the enduring psychological scars of survivors, continue to shape political discourse and social consciousness. Analyzing these long-term effects provides valuable lessons for developing effective recovery strategies and promoting long-term societal resilience.

Understanding the long-term effects of major historical disasters is essential for fostering a more comprehensive approach to disaster management. Recognizing the enduring consequences of these events underscores the importance of long-term planning, investment in resilient infrastructure, and the development of robust social safety nets. Furthermore, studying the long-term effects of past disasters provides valuable insights into the challenges of promoting psychological healing, fostering social cohesion, and addressing the complex interplay of physical, social, and economic factors in long-term recovery. By integrating this understanding into policy and practice, societies can work towards mitigating the long-term consequences of future disasters and building more resilient and sustainable communities.

7. Lessons Learned

Analysis of significant historical disasters reveals recurring themes and critical lessons applicable to contemporary disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies. These lessons underscore the importance of understanding cause-and-effect relationships, recognizing systemic vulnerabilities, and implementing effective preventative measures. The 1900 Galveston hurricane, for instance, demonstrated the devastating consequences of inadequate coastal defenses and insufficient warning systems, leading to significant advancements in hurricane forecasting and coastal engineering. Similarly, the Chernobyl disaster highlighted the critical need for stringent safety protocols in nuclear power plants and the importance of international cooperation in disaster response. Examining these historical precedents provides invaluable insights into the complex interplay of natural hazards, human actions, and technological vulnerabilities.

The practical significance of “lessons learned” as a component of studying historical disasters lies in their capacity to inform current policy and practice. By analyzing past failures and successes in disaster management, communities and nations can develop more effective strategies for mitigating risks and enhancing resilience. The implementation of building codes designed to withstand seismic activity, for example, reflects lessons learned from devastating earthquakes like the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake. The development of early warning systems for tsunamis, informed by the tragic consequences of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, demonstrates the practical application of historical analysis in saving lives and mitigating future impacts. Furthermore, understanding the social and economic consequences of past disasters, such as the widespread displacement and economic hardship following Hurricane Katrina, informs strategies for community recovery and long-term resilience building.

Effective disaster management necessitates a continuous process of learning from past events. Acknowledging the complex and often interconnected causes of disasters, investing in robust mitigation measures, and fostering international cooperation are crucial for minimizing future risks. Challenges remain in translating lessons learned into effective policy and practice, particularly in addressing underlying vulnerabilities related to poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation. However, by critically examining historical disasters and integrating these insights into planning and preparedness efforts, societies can strive towards a more disaster-resilient future.

Frequently Asked Questions about Major Historical Disasters

This section addresses common inquiries regarding historically significant catastrophic events, aiming to provide concise and informative responses.

Question 1: What defines a disaster as “major” in a historical context?

Several factors contribute to classifying a disaster as “major”: scale of destruction, loss of human life, long-term societal impact (social, economic, environmental), and the extent of geographical impact. Events significantly altering the course of history or profoundly impacting human societies often warrant this classification.

Question 2: Are natural disasters becoming more frequent?

While geological processes remain constant, some evidence suggests an increase in the frequency and intensity of certain weather-related disasters, potentially linked to climate change. Increased population density and human encroachment into hazardous areas also contribute to higher impacts from natural events.

Question 3: What can be learned from studying historical disasters?

Studying past catastrophes offers invaluable insights into human vulnerability, societal resilience, and the efficacy of various mitigation strategies. These lessons inform present-day disaster preparedness, urban planning, and policy development, contributing to more resilient communities.

Question 4: How do human actions contribute to the impact of disasters?

Human activities, such as deforestation, urbanization in hazardous areas, and greenhouse gas emissions, can exacerbate the impact of natural disasters. Industrial accidents and mismanagement of resources can also lead to catastrophic consequences.

Question 5: How has disaster management evolved over time?

Disaster management has evolved significantly, shifting from reactive responses to proactive mitigation and preparedness strategies. Advances in technology, improved communication systems, and increased international cooperation play crucial roles in modern disaster management.

Question 6: What are some key challenges in mitigating future disasters?

Key challenges include addressing underlying societal vulnerabilities, promoting sustainable development practices, fostering international collaboration, and accurately predicting and preparing for low-probability, high-impact events.

Understanding historical disasters and learning from past experiences are critical for building more resilient communities and mitigating the impact of future catastrophic events. Continued research, international cooperation, and proactive planning are essential for navigating the complex challenges posed by both natural and human-induced disasters.

The subsequent sections of this article will delve deeper into specific historical disasters, exploring their causes, consequences, and the enduring lessons they provide.

Conclusion

Exploration of significant historical disasters reveals consistent themes: human vulnerability in the face of natural forces, the complex interplay of social and environmental factors, and the enduring impact of such events on societal development. From pandemics like the Black Death to technological failures like Chernobyl, these events offer crucial insights into the challenges of disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Analysis of their scale, human cost, social disruption, and long-term effects underscores the importance of learning from the past to mitigate future risks.

Catastrophic events remain an inevitable aspect of human history. However, understanding the dynamics of these events empowers societies to adopt more proactive approaches to disaster management. Continued investment in research, technological advancements, and international cooperation is essential for building more resilient communities and mitigating the potentially devastating impacts of future disasters. Preserving the historical record of these events and critically examining the lessons learned remains paramount in navigating an uncertain future.