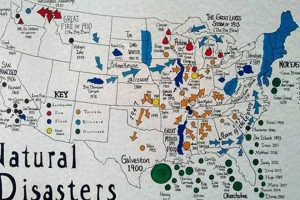

A potential source of harm, such as an earthquake, volcanic eruption, or flood, represents a dangerous natural phenomenon. However, only when such a phenomenon causes widespread destruction, loss of life, or significant societal disruption does it constitute a catastrophe. For instance, a landslide in an uninhabited area is a geological event, while the same landslide burying a town becomes a tragic incident.

Understanding the distinction between potential and actual destructive events is crucial for effective risk management and resource allocation. Recognizing inherent environmental dangers allows for proactive measures like early warning systems, resilient infrastructure, and community preparedness programs. This proactive approach minimizes the impact of these events, transforming potential catastrophes into manageable challenges. Historical analysis of past events informs present-day strategies, enabling communities to learn from previous experiences and bolster their defenses against future threats.

This foundational understanding of the difference between a dangerous natural process and the resulting devastation informs discussions on various related topics, including risk assessment methodologies, disaster preparedness strategies, and the societal and economic impacts of such events. It also provides a framework for exploring the complex interplay between human activities and the natural world, and how this relationship can exacerbate the consequences of natural phenomena.

Preparedness and Mitigation Strategies

Minimizing the impact of potentially destructive natural events requires a multifaceted approach encompassing both individual and community-level actions. The following strategies offer practical guidance for enhancing resilience and reducing vulnerability.

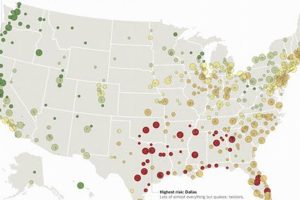

Tip 1: Understand Local Risks: Knowledge of regionally specific threats, whether seismic activity, flooding, or wildfires, forms the foundation of effective preparedness. Consulting local geological surveys and emergency management agencies provides valuable insights.

Tip 2: Develop an Emergency Plan: A comprehensive plan should outline evacuation routes, communication protocols, and designated meeting points. Regular drills ensure familiarity and preparedness.

Tip 3: Secure Property and Possessions: Reinforcing structures against anticipated threats, such as high winds or seismic activity, reduces potential damage. Securing valuable items protects against loss.

Tip 4: Assemble an Emergency Kit: Essential supplies, including water, non-perishable food, first-aid supplies, and communication devices, ensure self-sufficiency during the immediate aftermath.

Tip 5: Stay Informed: Monitoring weather alerts and official communication channels provides critical updates and enables timely responses to evolving situations.

Tip 6: Support Community Initiatives: Participating in local preparedness programs strengthens community resilience and fosters a culture of collective safety.

Tip 7: Insurance and Financial Preparedness: Adequate insurance coverage provides a financial safety net in the event of property damage or loss. Maintaining emergency funds further bolsters resilience.

By implementing these strategies, individuals and communities can significantly reduce their vulnerability to the disruptive impacts of environmental threats. These proactive measures contribute to a more secure and resilient future.

These combined efforts play a critical role in transitioning from reactive crisis management to proactive risk reduction, fostering safer, more resilient communities.

1. Potential Threat

The concept of “potential threat” forms the crucial link between a natural hazard and a disaster. A natural hazard, in its dormant state, represents a potential threata possibility of harm that may or may not materialize. Understanding this potential is fundamental to disaster preparedness and mitigation. This exploration delves into facets of potential threats, analyzing their characteristics and implications.

- Magnitude and Intensity:

The potential threat posed by a natural hazard is directly related to its potential magnitude and intensity. A powerful earthquake fault line near a densely populated area represents a significantly higher potential threat than a minor fault line in a remote location. The potential energy stored within a volcano influences the scale of a potential eruption and thus the extent of the threat. Categorizing these potential threats based on scientific data enables a more accurate risk assessment.

- Proximity to Vulnerable Populations:

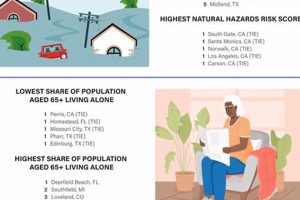

A natural hazard only transforms into a disaster when it impacts human populations. A remote volcanic eruption may present a minimal threat, while the same eruption near a city poses a catastrophic risk. Coastal communities are inherently more vulnerable to tsunamis than inland settlements. Population density and proximity to the hazard significantly influence the degree of potential threat.

- Recurrence Interval and Predictability:

Understanding the historical patterns of natural hazards informs our understanding of potential threats. Areas prone to frequent earthquakes face a consistently higher level of potential threat compared to regions with infrequent seismic activity. While predicting the precise timing of events remains challenging, understanding recurrence intervals allows for long-term preparedness planning.

- Mitigation and Preparedness Measures:

Existing mitigation measures and preparedness strategies influence the level of potential threat. Robust building codes in earthquake-prone zones reduce the potential impact, while early warning systems for tsunamis can minimize casualties. The presence or absence of these measures dramatically alters the potential threat landscape. Investment in these strategies is crucial to transforming potential threats into manageable risks.

By analyzing these facets of potential threatmagnitude, proximity to populations, recurrence intervals, and existing mitigation measuresa more comprehensive understanding of risk emerges. This understanding is essential for effective disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies, ultimately aiming to minimize the impact of natural hazards and prevent their escalation into disasters. The interplay of these factors dictates the level of risk a community faces and informs the necessary steps to mitigate potential harm.

2. Realized Impact

The realized impact of a natural hazard determines its classification as a disaster. A hazard, representing potential energy for harm, transitions into a disaster when that potential becomes kinetic, causing tangible, measurable effects. This impact spans various dimensions, from immediate physical destruction to long-term societal and economic disruption. Examining the realized impact clarifies the critical distinction between hazard and disaster.

Cause and effect relationships are central to understanding realized impact. A volcanic eruption (hazard) can lead to ashfall, lava flows, and pyroclastic surges (realized impacts). These impacts, in turn, trigger cascading effects, including infrastructure damage, agricultural losses, displacement of populations, and health crises. The extent of these cascading effects defines the severity of the disaster. For example, the 2010 Eyjafjallajkull eruption in Iceland, while not directly causing widespread destruction, had a significant realized impact on air travel across Europe due to ash clouds, illustrating that realized impact can extend far beyond the immediate vicinity of the hazard.

The concept of realized impact serves as a critical component in distinguishing a natural hazard from a disaster. While a hazard signifies a potential threat, a disaster is defined by the actual harm inflicted. This distinction has practical implications for disaster management. Resource allocation, relief efforts, and long-term recovery strategies are predicated on assessing the realized impact. Furthermore, understanding the diverse ways in which natural hazards manifest their impactfrom immediate physical damage to subtle, long-term ecological consequencesis crucial for developing comprehensive mitigation and adaptation strategies. The 1995 Kobe earthquake highlighted the devastating realized impact of seismic activity on dense urban environments, leading to revisions in building codes and urban planning strategies worldwide. Analyzing realized impact also underscores the complex interplay between natural events and human vulnerability, informing more effective strategies for reducing risk and enhancing community resilience. Ultimately, comprehending realized impact transforms reactive responses into proactive risk reduction, leading to more resilient communities and minimizing the human cost of natural hazards.

3. Human Vulnerability

Human vulnerability lies at the heart of the distinction between a natural hazard and a disaster. A natural hazard, a potential source of harm, only becomes a disaster when it intersects with human populations and their built environment. Understanding the factors that contribute to vulnerability is crucial for mitigating the impact of natural hazards and preventing them from escalating into disasters.

- Socioeconomic Factors:

Poverty, inequality, and lack of access to resources significantly increase vulnerability to natural hazards. Impoverished communities often reside in hazard-prone areas, lack resilient infrastructure, and have limited access to early warning systems and healthcare. The 2010 Haiti earthquake tragically demonstrated how socioeconomic disparities exacerbate the impact of natural hazards, resulting in disproportionately higher mortality rates in marginalized communities.

- Environmental Degradation:

Human activities, such as deforestation, urbanization, and unsustainable land management practices, can amplify the impact of natural hazards. Deforestation increases the risk of landslides, while urbanization intensifies the effects of flooding. The increased frequency and intensity of flooding in many parts of the world are partially attributed to human-induced environmental changes.

- Population Density and Distribution:

High population density in hazard-prone areas significantly increases the potential for large-scale disasters. Coastal cities, for instance, are particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise and storm surges. The concentration of populations in these areas magnifies the potential impact of natural hazards.

- Governance and Institutional Capacity:

Weak governance, inadequate disaster preparedness plans, and limited institutional capacity hinder effective disaster response and recovery. Corruption, lack of coordination among agencies, and insufficient resources can exacerbate the impact of natural hazards. The delayed response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 exposed vulnerabilities related to governance and institutional capacity.

These interconnected facets of human vulnerability highlight the complex relationship between natural hazards and human societies. Reducing vulnerability requires addressing these underlying factors through sustainable development practices, equitable resource allocation, and robust disaster preparedness strategies. Recognizing and mitigating human vulnerabilities is not only essential for minimizing the impact of disasters but also for fostering more resilient and equitable communities. By addressing these vulnerabilities, societies can shift from reactive crisis management to proactive risk reduction, creating a safer and more sustainable future.

4. Capacity to Cope

Capacity to cope represents a critical determinant in whether a natural hazard escalates into a disaster. This capacity encompasses the resources, strategies, and mechanisms available to individuals, communities, and nations to anticipate, withstand, and recover from the impacts of hazardous events. A high capacity to cope can significantly mitigate the consequences of a hazard, preventing it from becoming a full-blown disaster, while a low capacity exacerbates vulnerability, increasing the likelihood of widespread devastation. The interplay between the magnitude of a hazard and the capacity to cope dictates the ultimate outcome.

Cause and effect relationships are central to understanding the role of coping capacity. Effective early warning systems, for example, can significantly reduce casualties by providing timely information that enables evacuations and other protective measures. Robust infrastructure, designed to withstand the forces of earthquakes or floods, limits physical damage and economic losses. Well-trained emergency response teams and readily available medical resources enhance the ability to manage the immediate aftermath of an event, minimizing human suffering and accelerating recovery. Conversely, inadequate infrastructure, limited access to healthcare, and ineffective communication systems diminish coping capacity, amplifying the impact of even relatively minor hazards. The 1995 Kobe earthquake and the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, while of similar magnitudes, resulted in drastically different outcomes largely due to differences in building codes and disaster preparedness measures, highlighting the crucial role of coping capacity.

Understanding the factors that contribute to coping capacity is fundamental for disaster risk reduction. Investment in resilient infrastructure, development of comprehensive disaster preparedness plans, community education and awareness programs, and strengthening of institutional mechanisms all contribute to enhancing coping capacity. International cooperation and resource sharing play a crucial role in supporting vulnerable nations in developing their capacity to cope with natural hazards. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 emphasizes the importance of strengthening coping capacity as a core element of disaster risk reduction strategies globally. Recognizing and strengthening coping capacity transforms reactive crisis management into proactive risk reduction, fostering more resilient communities and ultimately minimizing the human and economic toll of natural hazards. This proactive approach acknowledges that while the forces of nature are often unpredictable, their impacts on human societies are not inevitable and can be significantly mitigated through strategic investment in coping capacity.

5. Loss and Disruption

Loss and disruption represent the defining consequences that distinguish a natural hazard from a disaster. While a hazard embodies potential harm, a disaster manifests as tangible loss and disruption across various societal sectors. Examining the multifaceted nature of these consequences provides crucial insights into disaster impact assessment, recovery strategies, and long-term risk reduction.

- Human Casualties and Displacement:

The most immediate and devastating consequence of a disaster is often the loss of human life. Disasters can cause widespread fatalities and injuries, leaving lasting emotional scars on affected communities. Forced displacement due to destroyed homes and infrastructure adds another layer of hardship, creating refugee crises and straining resources. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami tragically exemplifies the immense scale of human casualties and displacement that can result from a natural disaster.

- Economic Impacts:

Disasters inflict significant economic damage, impacting various sectors, including agriculture, industry, tourism, and infrastructure. Destruction of physical assets, disruption of supply chains, and loss of productivity contribute to substantial economic losses. The 1995 Kobe earthquake, for instance, resulted in massive economic disruption due to damage to port facilities and industrial infrastructure. These economic impacts can ripple through local and global economies, hindering long-term development.

- Damage to Critical Infrastructure:

Disasters often cause widespread damage to critical infrastructure, including transportation networks, communication systems, power grids, and healthcare facilities. Disruption of these essential services hinders rescue and relief efforts, exacerbates human suffering, and impedes recovery. The 2017 Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico demonstrated the devastating consequences of infrastructure damage, leaving the island without power and clean water for extended periods.

- Social and Psychological Impacts:

Beyond the immediate physical and economic impacts, disasters also have profound social and psychological consequences. Loss of loved ones, displacement, and disruption of social networks can lead to trauma, anxiety, and depression. The long-term psychological effects of disasters often go unrecognized but can significantly impede community recovery and resilience. The mental health toll of the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, for example, continues to affect individuals and communities years after the event.

These multifaceted losses and disruptions underscore the devastating consequences that elevate a natural hazard to the level of a disaster. Understanding these consequences is crucial not only for post-disaster recovery but also for proactive risk reduction strategies. By analyzing the patterns of loss and disruption associated with different types of disasters, communities can develop targeted mitigation measures, strengthen their coping capacity, and enhance their resilience in the face of future threats. Ultimately, minimizing loss and disruption constitutes the core objective of disaster risk reduction efforts worldwide.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the distinction between natural hazards and disasters, clarifying key concepts and dispelling misconceptions.

Question 1: Does the magnitude of a natural event automatically determine its classification as a disaster?

Magnitude plays a significant role, but it is not the sole determinant. A powerful earthquake in an uninhabited region constitutes a significant hazard but not necessarily a disaster. A smaller earthquake in a densely populated area, causing substantial damage and loss of life, is classified as a disaster. The impact on human populations and their built environment defines the event’s classification.

Question 2: Can human activities influence the transformation of a natural hazard into a disaster?

Human activities can significantly exacerbate the impact of natural hazards. Deforestation increases the risk of landslides, while urbanization intensifies flooding. Climate change, driven by human activities, alters weather patterns, increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. These actions heighten vulnerability and increase the likelihood of hazards escalating into disasters.

Question 3: What is the role of vulnerability in distinguishing hazards from disasters?

Vulnerability refers to the susceptibility of a population to the adverse impacts of natural hazards. Factors such as poverty, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to early warning systems increase vulnerability. A highly vulnerable population is more likely to experience a natural hazard as a disaster, even if the hazard itself is relatively minor.

Question 4: How does capacity to cope influence the impact of natural hazards?

Capacity to cope encompasses the resources, strategies, and mechanisms available to individuals, communities, and nations to anticipate, withstand, and recover from the impacts of natural hazards. High coping capacitythrough robust infrastructure, effective early warning systems, and efficient disaster preparedness planscan mitigate the impact of a hazard, preventing it from becoming a disaster. Conversely, low coping capacity increases vulnerability and the likelihood of a disaster.

Question 5: Is it possible to predict the occurrence of natural hazards and disasters?

While the precise timing and magnitude of natural hazards are difficult to predict, scientific understanding allows for hazard mapping and risk assessment. This knowledge informs land-use planning, building codes, and early warning systems. Predicting the precise moment an earthquake will strike remains a challenge; however, identifying earthquake-prone areas and implementing appropriate building codes minimizes potential damage.

Question 6: What is the significance of distinguishing between natural hazards and disasters?

The distinction informs effective resource allocation, disaster preparedness strategies, and risk reduction efforts. Understanding this differentiation allows for targeted interventions that reduce vulnerability, enhance coping capacity, and ultimately minimize the human and economic costs associated with the inevitable occurrence of natural hazards.

Understanding the complex relationship between natural hazards and disasters provides a foundation for developing effective risk reduction strategies. Proactive measures that address vulnerability and enhance coping capacity play a crucial role in building more resilient communities.

This understanding of natural hazards and disasters informs further discussion on risk assessment, disaster preparedness, and the development of sustainable mitigation strategies.

Natural Hazard vs Disaster

The exploration of “natural hazard vs disaster” reveals a crucial distinction: a hazard represents potential, while a disaster signifies realized impact. A hazard, such as a fault line or a volcano, exists as a latent threat. It becomes a disaster when it intersects with human vulnerability, exceeding coping capacity and resulting in tangible loss and disruption. Magnitude plays a role, but the defining factor lies in the interaction between the natural event and human systems. Socioeconomic factors, environmental degradation, and inadequate preparedness amplify vulnerability, transforming potential threats into devastating realities.

Understanding this distinction is paramount for effective risk reduction. Investing in resilient infrastructure, strengthening institutional capacity, and fostering a culture of preparedness are essential steps toward minimizing vulnerability and enhancing coping capacity. The distinction between “natural hazard vs disaster” is not merely semantic; it represents a critical framework for building more resilient societies, mitigating the human cost of natural events, and fostering a more sustainable future. The challenge lies not in preventing natural hazards, but in mitigating their potential to become disasters.