Defining the most catastrophic event in United States history presents a complex challenge. Catastrophes can be measured by various metrics: loss of life, economic damage, long-term societal impact, or a combination thereof. A pandemic, for instance, might claim more lives than a single natural event, but a large-scale natural disaster could cripple infrastructure and reshape the landscape for generations. Consideration must also be given to events like the Civil War, which caused immense human suffering and fundamentally altered the nation’s trajectory.

Understanding the scale and impact of historical calamities provides valuable perspective on national resilience and preparedness. Studying these events allows for analysis of governmental response, social adaptation, and long-term recovery efforts. This knowledge informs current policy decisions related to disaster preparedness, mitigation strategies, and resource allocation. Examining past tragedies also fosters a deeper understanding of national vulnerabilities and can inspire collective action to prevent or mitigate future crises.

This exploration will delve into various contenders for the title of most devastating event, examining their respective impacts from multiple perspectives. Factors considered will include immediate casualties, economic consequences, lasting effects on the environment and public health, and overall societal disruption. The analysis will encompass both natural disasters and human-caused events, offering a comprehensive overview of the nation’s most challenging historical moments.

Understanding Historical Catastrophes

Gaining insight from past calamities can inform present-day preparedness and mitigation efforts. The following offers guidance for approaching this complex subject.

Tip 1: Define the Metrics: Establish clear criteria for evaluating the “biggest” disaster. Is it loss of life, economic impact, or long-term societal change? Different metrics will yield different “biggest” disasters.

Tip 2: Consider the Timeframe: Events have varying short-term and long-term consequences. The immediate impact of a hurricane might seem larger than that of a slow-moving environmental crisis, but the long-term effects of the latter could be more devastating.

Tip 3: Contextualize the Event: Analyze events within their historical contexts. Societal vulnerabilities, available technologies, and governmental responses all shape the outcome of a disaster.

Tip 4: Examine Multiple Perspectives: Consider the experiences of diverse populations. Disasters often disproportionately affect vulnerable communities. Understanding these disparities is crucial for equitable disaster preparedness and response.

Tip 5: Learn from the Past: Analyze past responses to disasters. What worked well? What could have been done better? Applying these lessons can improve future mitigation and recovery efforts.

Tip 6: Focus on Prevention and Mitigation: While understanding past disasters is important, the ultimate goal should be to prevent or mitigate future ones. This requires proactive planning, investment in resilient infrastructure, and public awareness campaigns.

By examining historical catastrophes through these lenses, valuable insights can be gained to improve preparedness and resilience in the face of future challenges.

This analysis provides a framework for evaluating significant events in United States history and underscores the importance of learning from the past to build a more secure future.

1. Scale of Loss

Scale of loss serves as a critical metric in evaluating historical catastrophes. Quantifying loss, however, requires considering more than just immediate fatalities. While the sheer number of lives lost during events like the Civil War or the 1918 influenza pandemic undeniably contributes to their classification as major disasters, a comprehensive assessment must also encompass the broader scope of loss. This includes factors such as long-term health consequences, displacement of populations, destruction of infrastructure, and environmental damage. For example, the Dust Bowl, while causing relatively few direct fatalities, resulted in widespread agricultural devastation, economic hardship, and mass migration, significantly impacting the nation for years.

Furthermore, the scale of loss must be contextualized within the historical period. A loss of 1,000 lives in the 17th century represents a significantly larger percentage of the population than a similar loss today. Technological advancements and disaster preparedness measures also influence the scale of loss. A modern earthquake of a given magnitude might result in fewer casualties than a comparable earthquake a century ago due to improved building codes and emergency response systems. The long-term consequences also play a crucial role. Events like the Chernobyl disaster, while resulting in a relatively limited number of immediate fatalities, continue to cause health problems and environmental contamination decades later, significantly contributing to the overall scale of loss.

Accurately assessing the scale of loss presents significant challenges. Data collection methods and record-keeping practices have evolved over time, making comparisons across different eras difficult. Furthermore, certain types of loss, such as psychological trauma or cultural damage, are inherently difficult to quantify. Despite these challenges, understanding the scale of loss, in its various forms, remains essential for evaluating the magnitude of historical disasters and for informing strategies to mitigate future risks. This understanding emphasizes the multifaceted nature of disasters and the importance of comprehensive assessment beyond immediate casualties.

2. Economic Impact

Economic impact serves as a crucial lens through which to analyze historical disasters in the United States. Economic consequences can range from immediate disruptions to long-term structural changes, profoundly shaping a nation’s trajectory. Understanding these impacts is essential for evaluating the true magnitude of a disaster and for developing effective recovery strategies.

- Direct Costs

Direct costs encompass the immediate financial losses associated with a disaster. This includes physical damage to infrastructure, property loss, and business interruption. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, for instance, resulted in widespread destruction, requiring massive rebuilding efforts and generating substantial direct costs. Hurricane Katrina similarly inflicted billions of dollars in damage, crippling the Gulf Coast economy.

- Indirect Costs

Indirect costs represent the broader economic ripple effects of a disaster, often exceeding direct costs. These include lost productivity, supply chain disruptions, and decreased consumer spending. The COVID-19 pandemic provides a stark example, as lockdowns and social distancing measures led to widespread business closures, job losses, and reduced economic activity across various sectors. The 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan, while not a U.S. event, illustrates the global interconnectedness of economies and how a disaster in one location can disrupt supply chains and markets worldwide.

- Long-Term Economic Consequences

Disasters can have lasting impacts on economic structures and growth trajectories. The Great Depression, triggered by the 1929 stock market crash, profoundly reshaped the American economy, leading to widespread unemployment, bank failures, and government intervention. The Dust Bowl, while primarily an ecological disaster, had devastating long-term economic consequences for agricultural communities and contributed to the westward migration of farmers seeking new livelihoods.

- Recovery and Reconstruction

The economic impact of a disaster also encompasses the costs associated with recovery and reconstruction. These costs can be substantial, requiring significant public and private investment. The Marshall Plan, implemented after World War II, represents a large-scale example of post-disaster economic recovery efforts, albeit on an international scale. The rebuilding of New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina required extensive federal funding and highlighted the complexities of long-term recovery in the face of significant infrastructure damage.

Analyzing the economic impact of historical disasters reveals the complex interplay between immediate losses, long-term consequences, and the challenges of recovery. Understanding these economic dimensions is critical for assessing the overall magnitude of a disaster and for developing effective strategies to mitigate future risks and promote resilient economic systems. From the localized devastation of a major earthquake to the widespread disruption of a global pandemic, economic considerations play a central role in shaping the narrative of disaster and its enduring legacy.

3. Societal Disruption

Societal disruption serves as a critical indicator when evaluating the magnitude of historical disasters. Disruptions can manifest in various forms, ranging from immediate impacts on daily life to long-term transformations of social structures, cultural norms, and political landscapes. Examining the extent and nature of societal disruption provides crucial insights into a disaster’s overall significance.

Disasters often lead to immediate disruptions in essential services such as transportation, communication, healthcare, and education. Hurricane Katrina, for example, severely disrupted communication networks and healthcare access in New Orleans, compounding the challenges of rescue and recovery efforts. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in widespread school closures and disruptions to global supply chains, highlighting the interconnectedness of modern societies and their vulnerability to large-scale disruptions. These immediate disruptions can have cascading effects, exacerbating the challenges posed by the initial disaster and hindering recovery efforts. The displacement of populations following a disaster can further strain resources and create social tensions, as seen in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.

Beyond immediate disruptions, disasters can also lead to profound long-term societal changes. The Civil War fundamentally reshaped American society, leading to the abolition of slavery and the redefinition of national identity. The Great Depression spurred significant government intervention in the economy and social welfare programs, altering the relationship between citizens and the state. The 9/11 terrorist attacks led to increased security measures and heightened surveillance, transforming the way people travel and interact in public spaces. These long-term societal changes often reflect a reevaluation of values, priorities, and vulnerabilities in the wake of a major disaster. Understanding these long-term transformations is essential for comprehending the full impact of historical disasters and for shaping future policies and preparedness strategies. It is through the lens of societal disruption that the true magnitude and lasting legacy of a disaster can be fully appreciated.

4. Long-Term Consequences

Long-term consequences represent a crucial factor in determining the magnitude and historical significance of disasters. While immediate impacts like casualties and initial economic losses are readily apparent, the enduring repercussions often shape a nation’s trajectory for generations, influencing social structures, economic development, and environmental health. Understanding these long-term consequences is essential for accurately assessing the true cost of a disaster and for developing effective strategies for mitigation and future preparedness. The ramifications of certain events extend far beyond the immediate aftermath, casting long shadows over subsequent decades and even centuries.

Consider the long-term consequences of the American Civil War. While the immediate cost in human lives and economic destruction was staggering, the war’s legacy continues to shape American society. The abolition of slavery, though a monumental achievement, led to new challenges related to racial equality and social justice, issues that continue to resonate today. The war also resulted in lasting political and economic divisions between North and South, influencing regional development and political discourse for generations. Similarly, the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, while initially an ecological crisis, had profound long-term economic and social consequences, contributing to widespread poverty, migration, and the development of new agricultural practices. These examples illustrate the complex and often unforeseen ways in which the long-term consequences of a disaster can reshape a nation’s social fabric, economic landscape, and political future.

Analyzing long-term consequences often requires examining the interplay of multiple factors. Environmental disasters, for example, can trigger long-term health problems, economic decline, and social displacement. The Chernobyl disaster, while occurring outside the United States, provides a stark example of the enduring impact of environmental contamination, with health consequences and economic disruption continuing decades after the initial event. The long-term consequences of technological disasters, such as the Three Mile Island nuclear incident, can include changes in regulations, public perception of technology, and investment in safety measures. By understanding the complex interplay of these factors, policymakers, researchers, and communities can better prepare for and mitigate the long-term consequences of future disasters, striving to build more resilient systems and minimize the enduring impact of such events on society and the environment.

5. Geographic Scope

Geographic scope plays a crucial role in determining the magnitude and impact of disasters, particularly when considering the “biggest disaster in US history.” The spatial extent of an event significantly influences its potential for widespread destruction, economic disruption, and social upheaval. A localized event, while potentially devastating to a specific community, may not have the same far-reaching consequences as a disaster affecting a larger geographic area. The geographic scope also influences the complexity of response and recovery efforts, as wider-ranging disasters often require greater coordination and resource mobilization across multiple jurisdictions and agencies.

Consider the contrast between the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. While the San Francisco earthquake caused significant destruction and loss of life within a relatively confined geographic area, the Dust Bowl affected a vast swathe of the Great Plains, impacting agriculture, economies, and populations across multiple states. The broader geographic scope of the Dust Bowl resulted in widespread migration, economic hardship, and long-term environmental damage, arguably leading to a more profound and enduring national impact. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic, with its global reach, demonstrated the interconnectedness of modern societies and the potential for widespread disruption caused by a geographically expansive event. Conversely, events like Hurricane Katrina, while devastating to specific regions, have a more localized geographic scope, limiting their overall national impact compared to events affecting larger areas or multiple regions concurrently.

Understanding the relationship between geographic scope and disaster impact is essential for effective disaster preparedness and response. Factors such as population density, infrastructure vulnerability, and the presence of critical resources within the affected area all contribute to the overall consequences. Analyzing the geographic distribution of impacts can inform resource allocation, evacuation planning, and long-term recovery efforts. Recognizing the significance of geographic scope provides a crucial framework for assessing the relative magnitude of disasters and for developing strategies to mitigate the risks associated with events of varying spatial extents. This understanding allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of disasters and their potential to disrupt communities, economies, and the environment on local, regional, and national scales.

6. Event Type (Natural/Human-Made)

Categorizing disasters as either natural or human-made provides a crucial framework for understanding their underlying causes, potential impacts, and informing mitigation strategies. This distinction is particularly relevant when considering the “biggest disaster in US history,” as the classification influences how such events are perceived, studied, and addressed. While both natural and human-made disasters can result in significant loss of life, economic damage, and societal disruption, their origins and characteristics often dictate different approaches to preparedness, response, and recovery.

- Natural Disasters

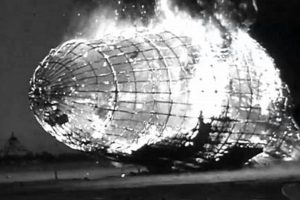

Natural disasters encompass events such as hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, wildfires, and pandemics. These events originate from natural processes and are often characterized by their unpredictability and potential for widespread destruction. Examples in US history include Hurricane Katrina, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, and the 1918 influenza pandemic. Assessing the magnitude of natural disasters requires considering their intensity, geographic scope, and the vulnerability of affected populations. Mitigation strategies for natural disasters often focus on early warning systems, building codes, and infrastructure development designed to withstand natural forces.

- Human-Made Disasters

Human-made disasters result from human actions or negligence, encompassing events such as industrial accidents, technological failures, terrorist attacks, and wars. Examples include the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the Chernobyl disaster (though not in the US, it offers valuable lessons), and the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The scale of human-made disasters can vary widely, from localized incidents to events with global consequences. Understanding the human factors contributing to these disasters is crucial for developing preventative measures and improving safety protocols. Often, investigations and subsequent policy changes are key components of the long-term response to human-made disasters.

- Complex Disasters

It is important to recognize that the distinction between natural and human-made disasters is not always clear-cut. Some events, termed “complex disasters,” involve an interplay of natural and human factors. For example, a natural disaster like a flood can exacerbate existing social vulnerabilities, leading to disproportionate impacts on marginalized communities. Climate change, driven by human activity, is also increasing the frequency and intensity of certain natural disasters, blurring the lines between natural and human-induced events. Recognizing the complex interactions between natural and human systems is essential for developing comprehensive disaster management strategies.

- Evaluating Historical Significance

When evaluating historical significance, considering the event type is crucial for understanding the context and long-term consequences. Human-made disasters often prompt investigations into systemic failures and lead to changes in regulations or safety protocols. Natural disasters, on the other hand, may highlight vulnerabilities in infrastructure and preparedness systems, prompting investments in resilience measures. Understanding the specific characteristics of each event type enables a more nuanced assessment of its impact and informs more effective strategies for mitigating future risks. Furthermore, societal responses to natural and human-made disasters can differ significantly, reflecting cultural values, political priorities, and the perceived level of human control over the event. These societal responses, in turn, can shape the long-term social, economic, and political consequences of the disaster. Examining these nuances is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the “biggest disaster in US history.”

By understanding the distinctions and interplay between natural and human-made disasters, one can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to their occurrence, their potential impacts, and the most effective strategies for mitigating future risks. This distinction, when applied to the context of US history, allows for a more nuanced assessment of the relative magnitude and enduring legacy of various catastrophic events, ultimately informing a more robust and effective approach to disaster preparedness and resilience building.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding significant historical disasters in the United States. Understanding these perspectives provides a deeper understanding of the complexities and nuances associated with evaluating catastrophic events.

Question 1: How does one objectively define the “biggest” disaster?

Defining the “biggest” disaster requires establishing specific criteria. Focusing solely on fatalities overlooks other crucial factors, such as economic impact, societal disruption, and long-term consequences. A multi-faceted approach considering all these elements offers a more comprehensive evaluation.

Question 2: Why is the Civil War often considered a leading contender for the “biggest disaster”?

The Civil War resulted in immense loss of life, reshaped the nation’s social and political landscape, and had enduring economic consequences. Its profound and lasting impact across multiple dimensions contributes to its prominence in discussions of the nation’s most significant historical tragedies.

Question 3: Can pandemics, like the 1918 influenza or COVID-19, be compared to other types of disasters?

Pandemics present unique challenges due to their widespread impact on public health, social structures, and economic stability. While different from localized events like earthquakes or hurricanes, their potential for widespread disruption and long-term consequences warrants comparison with other major disasters.

Question 4: How do technological advancements influence the impact of disasters?

Technological advancements can both mitigate and exacerbate the impacts of disasters. Improved building codes and early warning systems can reduce casualties, while complex interconnected systems can create new vulnerabilities and amplify the consequences of failures. Consideration of technological factors is crucial for understanding both risks and resilience.

Question 5: How do historical disasters inform present-day preparedness efforts?

Studying historical disasters provides valuable lessons regarding vulnerabilities, response effectiveness, and long-term recovery strategies. This knowledge informs current policies, infrastructure development, and public awareness campaigns, contributing to increased resilience and disaster preparedness.

Question 6: What role does historical context play in understanding the impact of disasters?

Societal structures, available resources, and cultural values at the time of a disaster significantly influence its impact. Understanding the historical context is essential for accurately assessing the consequences and learning from past experiences. This historical perspective helps contextualize the relative significance of different events and their lasting legacies.

By exploring these questions, a deeper understanding of the complexities associated with evaluating historical disasters can be achieved. Recognizing the diverse perspectives and factors involved contributes to a more nuanced and informed approach to disaster preparedness, mitigation, and recovery.

Further exploration of specific historical disasters will provide a more detailed analysis of their respective impacts and contributions to the ongoing discourse surrounding the nation’s most significant historical challenges.

Biggest Disaster in US History

Defining the “biggest disaster in US history” requires a nuanced understanding of various factors. This exploration examined key aspects such as scale of loss, economic impact, societal disruption, long-term consequences, geographic scope, and event type. From the immense human cost of the Civil War to the widespread economic devastation of the Great Depression and the global health crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic, each disaster presents a unique set of challenges and enduring legacies. Considering these diverse perspectives reveals the complexity inherent in ranking such events and underscores the importance of a multi-faceted approach to evaluation. Natural disasters, like hurricanes and earthquakes, demonstrate the power of nature to reshape landscapes and disrupt lives, while human-made disasters, such as industrial accidents and technological failures, highlight the potential consequences of human actions and the importance of safety regulations and preventative measures.

Ultimately, understanding historical disasters offers crucial lessons for building a more resilient future. By studying the past, vulnerabilities can be identified, preparedness strategies can be refined, and mitigation efforts can be strengthened. The ongoing analysis of historical disasters provides valuable insights for navigating present challenges and mitigating future risks, contributing to a more secure and prepared society. Continued research and open dialogue regarding these events remain essential for fostering a collective understanding of disaster’s multifaceted impacts and for promoting a proactive approach to safeguarding communities and mitigating the consequences of future catastrophes.