The phenomenon of private companies profiting from crises, whether natural disasters or human-made calamities, involves leveraging urgent needs for essential services and resources. For example, reconstruction contracts following a hurricane might be awarded to private firms at inflated prices due to the immediate demand. This exploitation of vulnerable situations for financial gain raises ethical concerns.

Understanding the interplay between crises and economic opportunities is crucial for analyzing social and political dynamics. Examining this dynamic provides insight into the potential for both positive and negative consequences, including rapid infrastructure development alongside potential exploitation. Historical precedents, such as the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, offer valuable case studies for examining this complex issue and informing future policy decisions aimed at mitigating potential harm and promoting ethical conduct.

This article will delve further into specific examples, analyzing the mechanisms at play, discussing the ethical implications, and exploring potential solutions for regulating this controversial practice.

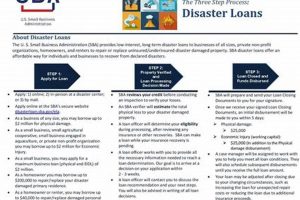

The following offers guidance for navigating the complex landscape of markets affected by catastrophic events. These insights aim to promote informed decision-making and responsible engagement.

Tip 1: Scrutinize Contract Terms: Carefully examine all proposed contracts, particularly those offered immediately following a disaster. Look for inflated pricing or unusual clauses that could indicate exploitative practices.

Tip 2: Prioritize Established Providers: When possible, rely on businesses with a proven track record of ethical conduct and fair pricing, rather than newly arrived entities seeking to capitalize on the crisis.

Tip 3: Advocate for Transparency: Demand transparency in pricing and resource allocation from both private companies and government agencies involved in disaster relief efforts.

Tip 4: Support Community-Based Initiatives: Prioritize local businesses and organizations that reinvest in the affected community, rather than external entities extracting profits.

Tip 5: Understand Regulatory Frameworks: Familiarize oneself with existing regulations and policies related to disaster relief and reconstruction to identify potential violations and advocate for stronger oversight.

Tip 6: Promote Ethical Procurement Practices: Encourage governments and aid organizations to adopt ethical procurement guidelines that prioritize fair competition and prevent exploitation.

Tip 7: Diversify Resources: Avoid over-reliance on single providers, particularly in the immediate aftermath of a crisis, to mitigate the risk of price gouging and ensure access to essential goods and services.

By adhering to these principles, individuals and communities can better protect themselves from exploitation and promote a more equitable and ethical response to crises.

This understanding fosters greater resilience and promotes a more just recovery process in the wake of disaster.

1. Crisis Exploitation

Crisis exploitation forms the core of disaster capitalism. It represents the calculated leveraging of vulnerabilities created by disasters, transforming human suffering and widespread need into profit-making opportunities. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for analyzing the ethical and societal implications of disaster response and recovery.

- Inflated Pricing of Essential Goods and Services

Disasters often disrupt supply chains and create urgent demand for necessities like food, water, shelter, and medical supplies. This allows opportunistic actors to charge exorbitant prices, exploiting the desperation of affected populations. Examples include price gouging on gasoline after hurricanes or inflated costs for temporary housing following earthquakes. This practice directly undermines equitable access to vital resources and exacerbates existing inequalities.

- Predatory Lending and Debt Traps

Individuals and communities struggling to rebuild after a disaster often face limited financial options. Predatory lenders capitalize on this vulnerability, offering high-interest loans with unfavorable terms. These loans can trap borrowers in cycles of debt, hindering long-term recovery and transferring wealth from disaster-stricken areas to financial institutions. This can be observed in the aftermath of floods, where individuals might take out high-interest loans to repair damaged homes, only to find themselves unable to repay the debt.

- Land Grabs and Displacement

Disasters can weaken land ownership claims and displace vulnerable populations. This creates opportunities for powerful actors, including corporations and developers, to acquire land at below-market value or through outright seizure. This displacement further marginalizes affected communities and disrupts traditional livelihoods. Examples include post-disaster land acquisitions for tourism development or the displacement of indigenous communities following environmental catastrophes.

- Privatization of Public Services

In the aftermath of disasters, governments sometimes turn to private companies to provide essential services like healthcare, education, or security. While private sector involvement can offer immediate assistance, it also creates potential for profit-seeking at the expense of public well-being. This can lead to reduced service quality, higher costs, and decreased accountability. The privatization of disaster relief efforts following Hurricane Katrina provides a prominent example of this phenomenon.

These interconnected facets of crisis exploitation highlight the systemic nature of disaster capitalism. By understanding these mechanisms, one can better analyze the power dynamics at play and advocate for more equitable and ethical responses to crises. Addressing these issues is crucial for building more resilient communities and ensuring that disaster recovery prioritizes human well-being over profit.

2. Profit-driven response

Profit-driven response represents a central component of disaster capitalism. It transforms essential services and resources required for recovery into commodities subject to market forces, often prioritizing profit maximization over equitable distribution and long-term community well-being. This dynamic can manifest in several ways. Private companies might charge inflated prices for essential goods and services due to increased demand and limited supply following a disaster. Reconstruction contracts might be awarded to well-connected firms rather than local businesses, hindering community recovery and diverting resources. Furthermore, lobbying efforts by powerful corporations can influence disaster-related policies, shaping regulations to favor private interests over public needs. For example, deregulation of environmental protections following a natural disaster could allow companies to exploit resources at the expense of long-term sustainability.

The consequences of prioritizing profit during disaster recovery can be far-reaching. Increased costs for essential goods and services can exacerbate existing inequalities, disproportionately impacting vulnerable populations who may lack the resources to afford inflated prices. The focus on short-term profits can also lead to neglect of long-term sustainability and community resilience, hindering effective rebuilding and increasing vulnerability to future disasters. For instance, prioritizing rapid, low-cost construction using substandard materials might yield immediate profits but result in infrastructure ill-equipped to withstand future events. Furthermore, a profit-driven approach can erode public trust in institutions and create a sense of exploitation, potentially leading to social unrest and hindering community cohesion. The privatization of disaster relief efforts following Hurricane Katrina serves as a stark example, where allegations of profiteering and mismanagement fueled public outrage and hampered recovery efforts.

Understanding the role of profit-driven responses in disaster capitalism is crucial for developing effective strategies to mitigate its negative consequences. Promoting transparency in contracting and resource allocation can help ensure equitable distribution of aid and prevent exploitation. Strengthening regulatory frameworks and oversight can limit profiteering and prioritize public well-being. Supporting community-based organizations and local businesses can foster a more equitable and sustainable recovery process. Addressing these complex issues is essential for building more resilient communities and fostering a more just and equitable response to disasters.

3. Privatization of Essential Services

Privatization of essential services represents a key component of disaster capitalism. By transferring control of crucial resources and services from public to private entities, opportunities emerge for profit maximization during times of heightened vulnerability. This shift can exacerbate existing inequalities and raise ethical concerns about prioritizing profit over human well-being in the wake of disaster.

- Healthcare Provision

Private healthcare providers may prioritize profitable procedures over essential, often less lucrative, care during emergencies. Following a natural disaster, for instance, a private hospital might focus on treating patients with private insurance who can afford elective surgeries, potentially delaying or neglecting care for those with life-threatening injuries who lack coverage. This prioritization of profit over need can have devastating consequences for vulnerable populations.

- Infrastructure Reconstruction

Private companies contracted for post-disaster reconstruction may prioritize cost-cutting measures and rapid completion over long-term resilience and community needs. Using substandard materials or neglecting proper building codes can maximize short-term profits but create unsafe structures ill-equipped to withstand future events. This was observed in some areas following Hurricane Katrina, where quickly constructed housing proved vulnerable to subsequent storms.

- Water and Sanitation Management

Privatization of water resources can lead to unequal access during crises. Private companies may prioritize supplying water to paying customers, potentially leaving marginalized communities without access to this essential resource. This can exacerbate existing inequalities and create public health crises in the aftermath of disasters, particularly in developing countries where access to clean water is already limited.

- Security and Emergency Services

Private security firms hired for disaster response may prioritize protecting private property over ensuring public safety. This can create a two-tiered system of security, where those who can afford private protection receive preferential treatment while vulnerable populations are left exposed. This dynamic can exacerbate social unrest and deepen existing inequalities in the aftermath of disasters.

These examples illustrate how the privatization of essential services can create vulnerabilities and exacerbate inequalities during times of crisis. By analyzing this dynamic within the context of disaster capitalism, a clearer understanding emerges of how profit motives can influence disaster response and recovery, often at the expense of equitable resource allocation and long-term community well-being. This underscores the need for robust regulatory frameworks and oversight to ensure that essential services remain accessible to all, regardless of socioeconomic status, during and after disasters.

4. Deregulation

Deregulation, often presented as a catalyst for economic growth and efficiency, can create vulnerabilities that exacerbate the negative consequences of disaster capitalism. Weakening or eliminating regulations designed to protect public interests, such as environmental safeguards, labor laws, or building codes, can create opportunities for exploitation during and after disasters. This dismantling of regulatory frameworks provides fertile ground for profiteering by reducing oversight and accountability, allowing private companies to operate with fewer constraints and potentially prioritize profit over public well-being.

For instance, relaxing environmental regulations after a natural disaster might expedite rebuilding efforts but also permit companies to bypass environmental impact assessments, leading to long-term environmental damage and increased vulnerability to future disasters. Similarly, weakening labor laws in the name of economic recovery can create conditions ripe for exploitation, with workers facing unsafe working conditions, suppressed wages, and limited legal recourse. The relaxation of building codes, while potentially reducing construction costs, can lead to the construction of substandard housing that places residents at greater risk during subsequent events. The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina provides a stark example of how deregulation, coupled with privatization, contributed to a flawed and inequitable recovery process. The relaxation of environmental regulations allowed for rapid but unsustainable development, while weakened labor protections left workers vulnerable to exploitation.

Understanding the connection between deregulation and the potential for disaster capitalism is crucial for developing effective disaster preparedness and recovery strategies. Robust regulatory frameworks, while sometimes perceived as impediments to economic growth, play a vital role in protecting vulnerable populations and ensuring equitable outcomes during times of crisis. Stronger oversight, transparent contracting processes, and community participation in decision-making are essential for mitigating the risks associated with deregulation and promoting a more just and sustainable recovery process. Failing to address these issues can create a cycle of vulnerability, where deregulation exacerbates the impacts of disasters, leading to further deregulation in the name of recovery, ultimately increasing the potential for future exploitation.

5. Social Inequality Exacerbation

Disaster capitalism, by its very nature, tends to amplify existing social inequalities. Crises disproportionately impact vulnerable populationsthose lacking economic resources, adequate housing, or social support networks. These pre-existing disparities become magnified when profit-driven responses prioritize resource allocation based on market principles rather than equitable distribution, leading to a widening gap between the haves and have-nots in the aftermath of disaster.

- Differential Access to Resources

Following a disaster, access to essential goods and services, such as food, water, shelter, and healthcare, often becomes commodified. Those with greater financial resources can secure these necessities, while marginalized communities face shortages, inflated prices, and limited access. This disparity in access exacerbates existing inequalities, leaving vulnerable populations disproportionately exposed to the health and economic consequences of the disaster.

- Unequal Recovery Trajectories

Disaster recovery efforts often prioritize areas with higher property values or greater economic potential, leaving marginalized communities to fend for themselves. This unequal distribution of resources and attention results in vastly different recovery trajectories, with wealthier areas bouncing back quickly while impoverished communities struggle for years, if not decades, to rebuild. This pattern reinforces existing socioeconomic disparities and deepens the cycle of poverty.

- Displacement and Marginalization

Disasters can displace vulnerable populations from their homes and communities, often leading to long-term marginalization. These displaced individuals may face difficulties accessing adequate housing, employment opportunities, and social support networks. This displacement can further entrench existing inequalities and create new forms of social stratification, as those with resources can relocate to more desirable areas, while those without are left to contend with the long-term consequences of displacement.

- Erosion of Social Safety Nets

Disaster capitalism can erode existing social safety nets by promoting privatization and deregulation. As governments divest from public services in favor of private sector involvement, essential resources and support systems become increasingly commodified and less accessible to vulnerable populations. This dismantling of social safety nets further exacerbates existing inequalities and leaves marginalized communities with fewer resources to cope with the aftermath of disasters.

These interconnected factors demonstrate how disaster capitalism systematically exacerbates social inequalities. By prioritizing profit over equitable resource allocation and community well-being, disaster capitalism deepens existing disparities and creates new forms of marginalization. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing more just and equitable disaster preparedness and recovery strategies that prioritize the needs of all members of society, not just those with the resources to navigate the market-driven landscape of disaster response.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the exploitation of crises for private gain.

Question 1: How does this phenomenon differ from legitimate business activity in post-disaster contexts?

Legitimate businesses provide essential goods and services at fair prices, contributing to recovery. Exploitation, however, involves inflated pricing, predatory lending, and prioritizing profit over community needs.

Question 2: What are the long-term consequences of unchecked exploitation of disasters?

Unchecked exploitation can lead to increased social inequality, hindered long-term recovery, erosion of public trust, and greater vulnerability to future disasters. It can create a cycle of disadvantage for affected communities.

Question 3: Are there specific regulations designed to prevent this exploitation?

Regulations vary by jurisdiction. Some regions have anti-price gouging laws or regulations related to disaster relief contracting. However, enforcement can be challenging, and loopholes often exist.

Question 4: How can individuals and communities mitigate the risks of exploitation following a disaster?

Individuals can scrutinize contracts, prioritize established providers, demand transparency, support community-based initiatives, and understand relevant regulations. Collective action and advocacy can strengthen community resilience.

Question 5: What role do government agencies play in either enabling or preventing this exploitation?

Government agencies can either exacerbate or mitigate the risks. Robust regulatory frameworks, ethical procurement practices, and transparent resource allocation can prevent exploitation. Conversely, deregulation and lack of oversight can create opportunities for profiteering.

Question 6: What are some historical examples of this phenomenon, and what lessons can be learned from them?

The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina provides a prominent example, highlighting the risks of privatization, deregulation, and inadequate oversight during disaster recovery. These lessons underscore the importance of strong regulatory frameworks, ethical procurement practices, and community-led recovery efforts.

Understanding the dynamics of crisis exploitation is crucial for promoting ethical and equitable disaster response and recovery. By addressing these frequently asked questions, individuals and communities can better navigate the complex landscape of post-disaster markets and advocate for policies that prioritize human well-being over profit.

The following section will explore specific case studies illustrating these dynamics in action.

Conclusion

This exploration has illuminated the multifaceted nature of disaster capitalismthe exploitation of crises for private gain. From inflated pricing of essential goods and services to the privatization of crucial public resources, the analysis has revealed how vulnerabilities created by disasters can be leveraged for profit, often exacerbating existing social inequalities and hindering long-term recovery. The interplay of deregulation, privatization, and profit-driven responses creates a complex web of systemic issues that demand careful consideration.

Unchecked, the pursuit of profit in the wake of catastrophe perpetuates a cycle of vulnerability and deepens social divisions. Addressing this challenge requires a fundamental shift in perspectiveone that prioritizes human well-being and community resilience over short-term economic gains. Strengthening regulatory frameworks, promoting ethical procurement practices, fostering community-led recovery efforts, and demanding transparency and accountability are crucial steps toward mitigating the harms of disaster capitalism and building a more just and equitable future. The imperative remains to ensure that responses to crises prioritize human needs and foster genuine recovery, rather than serving as opportunities for exploitation.