Past catastrophic events originating from natural processes, such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, floods, and droughts, constitute a significant area of study. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, which devastated Portugal and surrounding areas, serves as a prime example of such an event, demonstrating the immense destructive power of these phenomena.

Studying these past occurrences provides valuable insights into the Earth’s dynamic systems and their potential impact on human societies. Analysis of past events contributes to improved hazard assessment, enabling more effective mitigation strategies and disaster preparedness planning. This understanding is critical for reducing vulnerability and building resilience in communities facing similar threats. Furthermore, examination of these events within their historical context illuminates the complex interplay between natural forces and human response, offering valuable lessons for future generations.

This exploration delves further into specific categories of past catastrophic events, examining their characteristics, impacts, and the lessons learned. Further sections will address specific case studies, advancements in predictive modeling, and the ongoing evolution of disaster management strategies.

Lessons from Past Catastrophes

Examining past catastrophic natural events offers crucial insights for enhancing disaster preparedness and building more resilient communities. The following points highlight key takeaways from the study of these events.

Tip 1: Understand Local Hazards: Research the specific natural hazards prevalent in a given region. Coastal areas are more susceptible to tsunamis and hurricanes, while regions near fault lines face earthquake risks. Knowledge of local hazards informs appropriate preparedness measures.

Tip 2: Develop Evacuation Plans: Establish clear evacuation routes and procedures. The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa underscores the importance of swift, organized evacuations in volcanic regions. Practice these plans regularly to ensure effective implementation during a crisis.

Tip 3: Secure Infrastructure: Design and construct infrastructure with resilience to natural hazards in mind. Buildings in earthquake-prone zones require specific structural reinforcements. Consider the historical impact of events like the 1906 San Francisco earthquake when developing building codes and land-use policies.

Tip 4: Early Warning Systems: Invest in and maintain robust early warning systems. These systems, vital for timely evacuations and minimizing casualties, have proven crucial in mitigating the impact of events like the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

Tip 5: Community Education: Implement comprehensive public education programs focused on disaster preparedness. Regular drills and readily available information empower individuals to respond effectively during emergencies, reducing panic and enhancing community resilience.

Tip 6: Preserve Historical Data: Maintain meticulous records of past events, including their magnitude, impact, and community responses. This historical data provides valuable insights for refining predictive models and developing more effective mitigation strategies.

By integrating these lessons from past catastrophes into current disaster management strategies, communities can significantly reduce vulnerability and build greater resilience against future threats.

This analysis of historical natural disasters emphasizes the importance of proactive planning and preparation. The concluding section will offer further resources and recommendations for ongoing learning and community engagement.

1. Magnitude

Magnitude, a crucial factor in analyzing historical natural disasters, quantifies the size and energy release of an event. Understanding the magnitude of past events allows for comparative analysis, revealing patterns and trends crucial for risk assessment. The Richter scale, for example, quantifies earthquake magnitude, providing a framework for comparing events like the 1960 Valdivia earthquake (magnitude 9.5) and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake (magnitude 7.9). This comparison illustrates the vast difference in energy release and potential for destruction. Magnitude also directly correlates with the extent of impact, influencing the severity of damage to infrastructure, the geographic reach of the disaster’s effects, and the resultant societal disruption.

Precise magnitude estimations enhance the accuracy of hazard maps and inform building codes. Analyzing the magnitude of historical tsunamis, like the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, enables scientists to model potential inundation zones, guiding coastal development and evacuation planning. Furthermore, understanding the relationship between magnitude and frequency provides valuable insights into long-term risk. While high-magnitude events are less frequent, their potential for catastrophic consequences necessitates thorough preparedness. Conversely, low-magnitude events, though more frequent, can still pose significant cumulative risks over time.

Accurate assessment of magnitude poses significant challenges, particularly for historical events preceding modern instrumentation. Reconstructing the magnitude of pre-instrumental events relies on historical accounts, geological evidence, and proxy data, introducing potential uncertainties. Despite these challenges, ongoing research refines magnitude estimations, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of past disasters and enabling more effective risk mitigation strategies for the future. This improved understanding underscores the importance of interdisciplinary approaches, combining historical research, geological analysis, and advanced modeling techniques to enhance disaster preparedness and build more resilient communities.

2. Frequency

Frequency, in the context of historical natural disasters, refers to the rate at which events of a specific type and magnitude occur within a given timeframe and geographic area. Analyzing frequency patterns is essential for understanding long-term risks, informing land-use planning, and developing effective mitigation strategies. Examining historical records reveals crucial insights into the recurrence intervals of various natural hazards, enabling more accurate risk assessments.

- Return Periods

Return periods estimate the average time interval between events of a certain magnitude. For instance, a 100-year flood indicates a 1% annual probability of occurrence. Understanding return periods is crucial for infrastructure design, insurance assessments, and long-term planning. However, it is critical to remember that these are statistical averages, and actual occurrences can deviate. Multiple “100-year floods” can occur within a shorter timeframe, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on return periods.

- Temporal Clustering

Some natural disasters exhibit temporal clustering, meaning they occur more frequently within specific periods. Earthquake aftershocks, for example, demonstrate clustering, with numerous smaller tremors following a major event. Volcanic eruptions can also exhibit periods of heightened activity. Analyzing temporal clustering aids in short-term risk assessment and informs immediate response strategies following initial events.

- Spatial Distribution

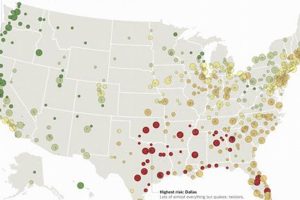

Frequency analysis often incorporates spatial considerations. Certain regions experience higher frequencies of specific hazards due to their geological or geographical characteristics. Coastal areas are more susceptible to hurricanes and tsunamis, while regions near tectonic plate boundaries experience more frequent earthquakes. Understanding spatial distribution patterns is vital for targeted resource allocation and regional preparedness planning.

- Influencing Factors

Various factors influence the frequency of natural disasters. Climate change, for instance, can alter weather patterns, potentially increasing the frequency of extreme events like floods and droughts. Human activities, such as deforestation and urbanization, can also exacerbate the impact and frequency of certain hazards. Analyzing these influencing factors provides insights into long-term trends and informs strategies for mitigating future risks.

The frequency of historical natural disasters provides critical data for understanding risk and vulnerability. Combining frequency analysis with data on magnitude, geographic distribution, and societal impact enables a comprehensive approach to disaster preparedness, contributing to the development of more resilient communities and effective mitigation strategies.

3. Geographic Location

Geographic location plays a pivotal role in the distribution and impact of historical natural disasters. The Earth’s dynamic systems, including tectonic plate boundaries, atmospheric circulation patterns, and ocean currents, create distinct zones of vulnerability to specific hazards. Understanding these spatial relationships is fundamental to assessing risk, predicting potential impacts, and developing effective mitigation strategies.

Coastal regions, for instance, face heightened susceptibility to tsunamis, storm surges, and coastal erosion. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan tragically demonstrated the devastating consequences of these combined hazards in a densely populated coastal area. Similarly, communities situated near active volcanoes, such as Pompeii in 79 AD, face the threat of pyroclastic flows, lahars, and ashfall. Analyzing the geographic distribution of past volcanic eruptions allows for the identification of high-risk zones and informs land-use planning decisions. Furthermore, proximity to major fault lines significantly elevates earthquake risk. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, resulting from movement along the San Andreas Fault, exemplifies the destructive potential of seismic activity in densely populated urban areas. Mapping historical earthquake epicenters reveals patterns of seismic activity and aids in identifying areas requiring stringent building codes and earthquake-resistant infrastructure.

Analyzing the geographic distribution of historical natural disasters provides crucial insights into regional vulnerabilities. This understanding is instrumental in developing targeted preparedness measures, allocating resources effectively, and implementing building codes appropriate for specific hazard profiles. While geographic location defines inherent risk, it does not determine destiny. Integrating geographic analysis with comprehensive disaster preparedness strategies empowers communities to mitigate potential impacts, enhancing resilience and minimizing the human cost of natural disasters.

4. Impact on Society

Historical natural disasters have profoundly impacted societies throughout history, shaping demographics, economies, and cultural landscapes. Analyzing these societal impacts provides crucial insights for understanding long-term consequences, informing present-day disaster preparedness strategies, and fostering more resilient communities.

- Demographic Shifts

Catastrophic events can trigger significant demographic shifts, including population displacement, migration patterns, and mortality rates. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, for example, resulted in substantial population loss and prompted significant outward migration. The Irish Potato Famine, while not strictly a geological or meteorological event, demonstrates the demographic impact of natural forces, leading to widespread starvation and emigration. Understanding these demographic consequences is crucial for post-disaster recovery planning and resource allocation.

- Economic Disruptions

Natural disasters often cause widespread economic disruption, impacting agriculture, infrastructure, and trade networks. The 1923 Great Kant earthquake severely damaged Tokyo’s infrastructure, leading to significant economic losses and long-term recovery efforts. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami disrupted global supply chains and impacted the Japanese economy for years. Analyzing historical economic consequences informs risk assessments for critical infrastructure and guides economic diversification strategies to enhance resilience.

- Cultural and Psychological Impacts

The cultural and psychological impacts of natural disasters can be profound and long-lasting. Traumatic experiences can lead to collective grief, post-traumatic stress, and changes in community identity. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD buried Pompeii, preserving a snapshot of Roman life but also representing a collective trauma. Understanding these cultural and psychological impacts is crucial for providing adequate mental health support in post-disaster recovery and for preserving cultural heritage.

- Political and Social Change

Natural disasters can act as catalysts for political and social change. The response to the 1906 San Francisco earthquake led to significant advancements in building codes and urban planning. The handling of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 exposed social inequalities and prompted discussions on disaster preparedness and response protocols. Analyzing these historical precedents provides valuable lessons for governance, policy development, and community organization to enhance resilience and mitigate future risks.

The societal impacts of historical natural disasters are multifaceted and far-reaching. By examining these diverse consequencesdemographic shifts, economic disruptions, cultural and psychological impacts, and political and social changewe gain a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between natural events and human societies. This historical perspective provides invaluable insights for developing effective strategies to mitigate future risks, enhance community resilience, and foster more sustainable and equitable societies.

5. Lessons Learned

Examining historical natural disasters provides a crucial opportunity to extract valuable lessons, informing present-day disaster preparedness strategies and fostering more resilient communities. These lessons, derived from the successes and failures of past responses, offer critical insights into mitigating future risks and minimizing human suffering. The relationship between historical events and lessons learned is cyclical, with each disaster offering an opportunity to refine protocols, improve infrastructure, and enhance community preparedness.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, for example, highlighted critical deficiencies in building codes and emergency response systems. The devastating fires that followed the earthquake exposed the vulnerability of densely populated urban areas with limited fire suppression capabilities. This catastrophe led to significant advancements in building codes, emphasizing fire-resistant materials and structural integrity. Similarly, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami underscored the critical need for robust early warning systems. The absence of a widespread tsunami warning system in the Indian Ocean basin contributed to the immense loss of life. This tragedy spurred the development of the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System, a testament to the power of lessons learned in driving tangible improvements in disaster preparedness.

Analyzing the cause-and-effect relationships within historical natural disasters reveals recurring themes. Inadequate infrastructure, insufficient communication systems, and limited public awareness frequently exacerbate the impact of these events. Conversely, robust building codes, effective early warning systems, and comprehensive community education programs demonstrably mitigate the consequences. Understanding these patterns enables a proactive approach to disaster preparedness, shifting from reactive crisis management to preventative risk reduction. Challenges remain, however, in translating lessons learned into actionable policies and sustained community engagement. Effective disaster risk reduction requires ongoing investment in infrastructure, education, and international collaboration to ensure that lessons from the past translate into a safer future.

6. Predictive Modeling

Predictive modeling plays a crucial role in understanding and mitigating the risks associated with natural disasters. By analyzing historical data, scientists develop models to forecast future events, assess potential impacts, and inform disaster preparedness strategies. These models leverage the patterns and trends observed in past events to project future scenarios, enabling proactive measures to reduce vulnerability and enhance community resilience. The accuracy and reliability of predictive models depend heavily on the quality and comprehensiveness of historical data, highlighting the importance of meticulous record-keeping and ongoing research.

- Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis forms the foundation of many predictive models for natural disasters. By analyzing historical records of earthquake occurrences, for instance, seismologists can identify patterns in magnitude, frequency, and location. These patterns inform statistical models used to estimate probabilities of future earthquakes in specific regions. Similarly, analyzing historical rainfall data enables hydrologists to develop flood prediction models, informing flood plain management and evacuation planning. Statistical methods, while powerful, are limited by the assumption that past trends will continue into the future. Changes in climate patterns or geological activity can influence future events in ways not fully captured by historical data.

- Geospatial Modeling

Geospatial modeling integrates geographical data with historical records to visualize and analyze the spatial distribution of natural hazards. By mapping historical earthquake epicenters, for example, geospatial models can identify fault lines and areas of heightened seismic activity. Overlaying this information with population density maps reveals areas of greatest potential risk. Similarly, geospatial models can integrate topography, land cover, and historical flood data to predict inundation zones during future flood events, informing land-use planning and evacuation routes. The integration of geospatial data enhances the precision and accuracy of predictive models, enabling more targeted and effective mitigation strategies.

- Simulation and Forecasting

Advanced simulation techniques, often incorporating high-performance computing, enable scientists to create complex models that simulate the dynamics of natural disasters. Hurricane forecasting models, for example, simulate atmospheric conditions, ocean currents, and historical storm tracks to predict the trajectory and intensity of future hurricanes. These simulations inform evacuation orders, resource allocation, and emergency response planning. Similarly, tsunami simulation models predict wave propagation and inundation zones based on historical earthquake data and bathymetric maps, aiding coastal communities in developing effective evacuation plans. Advances in computational power and modeling techniques continuously improve the accuracy and resolution of these simulations, providing more detailed and reliable predictions.

- Data Assimilation and Uncertainty Quantification

Modern predictive models increasingly incorporate data assimilation techniques, integrating real-time observations from sensor networks, satellite imagery, and ground-based monitoring systems. This continuous influx of data refines model predictions and enhances their accuracy. However, predictive models inherently involve uncertainties due to limitations in data availability, incomplete understanding of complex natural processes, and the chaotic nature of some events. Quantifying these uncertainties is crucial for communicating risk effectively and developing robust mitigation strategies. Uncertainty estimates provide a range of potential outcomes, allowing decision-makers to consider best-case and worst-case scenarios and adapt strategies accordingly.

Predictive modeling, by integrating statistical analysis, geospatial modeling, simulation techniques, and advanced data assimilation, provides a powerful toolset for understanding and mitigating the risks associated with natural disasters. While these models offer invaluable insights, their limitations must be acknowledged. Ongoing research, data collection, and model refinement are essential for improving predictive accuracy and empowering communities to prepare for, respond to, and recover from the inevitable impacts of future natural disasters.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the study and impact of significant past catastrophic events stemming from natural processes.

Question 1: How do historical natural disasters inform present-day disaster preparedness strategies?

Analysis of past events reveals recurring vulnerabilities in infrastructure, communication systems, and community preparedness. These insights inform the development of more robust building codes, early warning systems, and evacuation plans, contributing to enhanced resilience.

Question 2: Can studying historical natural disasters help predict future events?

While precise prediction remains a challenge, historical data informs predictive models, enabling estimations of probability, potential magnitude, and likely impacted areas. This information guides proactive mitigation efforts and resource allocation.

Question 3: What are some key limitations in the study of historical natural disasters?

Data availability varies significantly across different time periods and geographic regions. Historical records may be incomplete or lack the precision of modern instrumentation, introducing uncertainties into analyses. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of Earth’s systems introduces inherent unpredictability.

Question 4: How does the geographic location influence the impact of natural disasters?

Proximity to tectonic plate boundaries, coastlines, or volcanic regions elevates specific risks. Geographic analysis informs targeted preparedness measures and infrastructure development tailored to regional hazard profiles.

Question 5: What role does climate change play in the frequency and intensity of natural disasters?

Climate change influences weather patterns, sea levels, and other environmental factors, potentially altering the frequency and intensity of certain hazards like floods, droughts, and extreme weather events. Analyzing historical trends alongside climate projections informs adaptive strategies.

Question 6: How can communities leverage historical data to build resilience against future disasters?

By integrating historical data into comprehensive disaster preparedness plans, communities can identify vulnerabilities, develop effective mitigation strategies, and educate residents about potential risks. This proactive approach enhances community resilience and minimizes the human cost of future disasters.

Understanding past events provides crucial insights for navigating future challenges. Integrating these lessons into policy, planning, and community action strengthens disaster preparedness and fosters more resilient societies.

The subsequent section will explore specific case studies, illustrating the diverse impacts of historical natural disasters and the lessons learned.

Conclusion

Exploration of significant past catastrophic events originating from natural processes reveals critical insights into the complex interplay between human societies and the Earth’s dynamic systems. Analysis of magnitude, frequency, geographic distribution, and societal impact underscores the importance of understanding these events within their historical context. Lessons learned from past disasters, from the 1755 Lisbon earthquake to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, inform present-day disaster preparedness strategies, highlighting the critical role of robust infrastructure, early warning systems, and community education. Predictive modeling, informed by historical data, provides a powerful tool for assessing future risks and guiding mitigation efforts. Understanding these past events is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical component of building more resilient communities and mitigating the human cost of future disasters.

Continued investigation of these events remains essential for enhancing preparedness and fostering greater resilience in the face of ongoing natural hazards. The imperative to learn from the past offers not only a path toward a safer future but also a deeper understanding of the intricate relationship between humanity and the planet. Integrating historical analysis, scientific advancements, and community engagement provides the foundation for mitigating risks and building a more sustainable and secure future for all.