A dangerous natural phenomenon, such as an earthquake, volcanic eruption, or hurricane, poses a threat to life and property. When such an event causes widespread damage and disruption, exceeding a community’s ability to cope without external assistance, it becomes a catastrophe. For instance, a landslide in a sparsely populated area might be a hazardous event, but not a catastrophe. However, the same landslide impacting a densely populated city would likely constitute a catastrophic event due to the extensive damage and loss of life.

Understanding the difference between potential threats and actual catastrophic outcomes is critical for effective disaster risk reduction. Historically, societies have grappled with the impacts of these events, leading to the development of building codes, early warning systems, and evacuation plans. These measures aim to minimize the human and economic costs associated with such events by reducing vulnerability and enhancing resilience. Recognizing the escalating risks associated with climate change underscores the growing importance of proactive mitigation and preparedness strategies.

This article will further explore specific types of these phenomena, their underlying causes, and effective strategies for mitigating their impacts. Topics covered will include preparedness planning, response protocols, and long-term recovery efforts.

Preparedness and Mitigation Tips

Minimizing the impact of potentially catastrophic natural events requires proactive planning and mitigation. The following tips offer guidance for enhancing preparedness and resilience.

Tip 1: Develop an Emergency Plan: Create a household emergency plan that includes evacuation routes, communication protocols, and a designated meeting point. This plan should address the specific needs of all household members, including pets.

Tip 2: Assemble an Emergency Kit: Prepare a kit containing essential supplies such as water, non-perishable food, first-aid supplies, medications, and a battery-powered radio. Ensure the kit is readily accessible and periodically check and replenish its contents.

Tip 3: Secure Your Property: Take steps to protect your home or business from potential damage. This may involve reinforcing roofs, installing storm shutters, or elevating critical infrastructure. Landscaping choices can also play a role in mitigating risks.

Tip 4: Stay Informed: Monitor weather reports and official alerts from local authorities. Understand the specific risks prevalent in your area and familiarize yourself with community warning systems.

Tip 5: Educate Yourself and Your Family: Learn about different types of hazardous events and their potential impacts. Participate in community disaster preparedness training or drills to gain practical skills and knowledge.

Tip 6: Consider Insurance Coverage: Evaluate insurance policies to ensure adequate coverage for potential damages associated with relevant natural events.

Tip 7: Support Community Resilience: Engage with local organizations and initiatives focused on disaster preparedness and mitigation. Community-based efforts can significantly enhance overall resilience.

By taking these proactive steps, individuals and communities can significantly reduce their vulnerability to the devastating impacts of these events and foster a culture of preparedness.

These preparedness and mitigation strategies are crucial for minimizing loss and facilitating recovery. The following section will explore the crucial role of community-level response and long-term recovery efforts.

1. Natural Processes

Natural processes, the fundamental drivers of Earth’s dynamic systems, shape the planet’s landscape and influence the occurrence of hazardous events. Understanding these processes is essential for comprehending the nature and potential impact of such phenomena.

- Geological Processes:

Tectonic plate movement, the driving force behind earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, exemplifies a geological process with significant hazard potential. The 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile, the largest earthquake ever recorded, demonstrates the devastating impact of these processes. Fault lines, zones of weakness in the Earth’s crust, represent areas of heightened seismic activity. Volcanic eruptions, like the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, can cause widespread ashfall, lahars, and atmospheric disturbances.

- Hydrometeorological Processes:

Hydrometeorological processes encompass atmospheric, hydrological, and oceanographic phenomena. Hurricanes, such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005, illustrate the destructive power of extreme weather events driven by these processes. Floods, often triggered by intense rainfall or snowmelt, can inundate vast areas, causing extensive damage and displacement. Droughts, prolonged periods of abnormally low rainfall, can lead to water shortages and crop failures.

- Geomorphological Processes:

Geomorphological processes, encompassing the shaping of Earth’s surface, contribute to hazards such as landslides and avalanches. Landslides, often triggered by heavy rainfall or earthquakes, can bury entire communities. Avalanches, rapid downslope movements of snow and ice, pose significant risks in mountainous regions. Coastal erosion, a gradual process exacerbated by storms and sea-level rise, threatens coastal communities and infrastructure.

- Biological Processes:

While less frequently considered in the context of large-scale disasters, biological processes can also contribute to hazards. Wildfires, often ignited by lightning or human activity, can consume vast tracts of land, posing risks to human life and property. Disease outbreaks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrate the potential for biological processes to cause widespread disruption and loss of life. Harmful algal blooms, triggered by excessive nutrient runoff, can contaminate water supplies and impact marine ecosystems.

These diverse natural processes, while integral to Earth’s dynamic environment, can generate hazardous events with significant societal consequences. Understanding their underlying mechanisms and potential impacts is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies and enhancing community resilience.

2. Potential for Harm

The potential for harm inherent in natural processes is the defining characteristic that elevates a natural hazard to a natural disaster. This potential encompasses the capacity to inflict damage, disrupt societal functions, and cause loss of life. Examining the various facets of this potential provides crucial insights for risk assessment and mitigation strategies.

- Magnitude and Intensity:

The magnitude and intensity of a natural event directly correlate with its potential for harm. A high-magnitude earthquake, like the 9.1 magnitude Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011, can cause significantly more devastation than a lower-magnitude tremor. Similarly, the intensity of a hurricane, measured by wind speed and storm surge, determines its destructive capacity.

- Frequency and Probability:

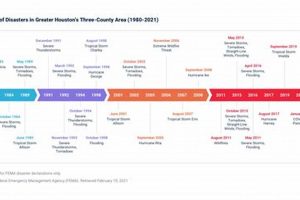

While high-magnitude events pose the greatest threat, the frequency and probability of lower-magnitude events also contribute to the overall risk. Frequent flooding in a particular region, even if relatively low in intensity each time, can cumulatively cause substantial damage and disruption over time. Understanding the statistical likelihood of different events is crucial for long-term planning and resource allocation.

- Area of Impact:

The geographical extent of a natural hazards impact significantly influences the potential for harm. A widespread volcanic eruption, like the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, can have global climatic consequences, whereas a localized landslide primarily affects the immediate area. The area of impact determines the scale of the response required and the resources needed for recovery.

- Vulnerability of Exposed Elements:

The vulnerability of the elements exposed to a natural hazard including human populations, infrastructure, and ecosystems is a critical factor in determining the potential for harm. A densely populated coastal city is inherently more vulnerable to a tsunami than a sparsely populated inland area. Building codes, land-use planning, and early warning systems play a vital role in reducing vulnerability and minimizing potential losses.

Understanding these interconnected facets of potential harm is paramount for effective disaster risk reduction. By analyzing the magnitude and intensity of potential hazards, assessing their frequency and probability, evaluating the potential area of impact, and addressing the vulnerability of exposed elements, communities can develop comprehensive strategies to mitigate the devastating consequences of natural disasters.

3. Human Vulnerability

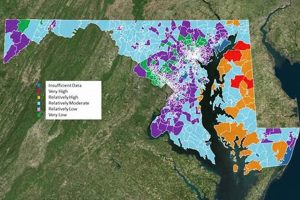

Human vulnerability forms a critical link between the existence of a natural hazard and the occurrence of a natural disaster. While the power of natural processes cannot be controlled, human vulnerability significantly influences the extent of the damage and disruption experienced. This vulnerability stems from a combination of factors, including physical location, socioeconomic conditions, and societal preparedness.

Settlements situated on floodplains, coastal areas, or near fault lines experience higher exposure to specific hazards. Socioeconomic disparities influence access to resources and information, impacting a community’s capacity to prepare for and recover from disasters. Marginalized communities often face greater vulnerability due to limited access to safe housing, healthcare, and early warning systems. The 2010 Haiti earthquake tragically demonstrated how pre-existing vulnerabilities exacerbated the impact of a natural hazard, resulting in a catastrophic disaster with immense loss of life.

Furthermore, inadequate infrastructure, insufficient building codes, and limited disaster preparedness planning amplify vulnerability. The absence of robust early warning systems and evacuation plans can hinder effective response, leading to increased casualties and economic losses. Conversely, investments in resilient infrastructure, community education, and early warning systems demonstrably reduce human vulnerability and mitigate the impacts of natural hazards. The implementation of stringent building codes in earthquake-prone areas, for example, has proven effective in reducing structural damage and protecting lives. Understanding and addressing human vulnerability is therefore paramount for transforming approaches to disaster risk reduction from reactive response to proactive mitigation.

In summary, recognizing human vulnerability as a central component of disaster risk necessitates a shift towards proactive and inclusive strategies. Addressing the root causes of vulnerability including poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation is crucial for building resilient communities. By prioritizing investments in disaster preparedness, risk reduction measures, and community empowerment, societies can effectively minimize the impact of natural hazards and avert future catastrophes.

4. Exceeding Coping Capacity

A natural hazard transforms into a natural disaster when the affected community’s capacity to cope is overwhelmed. This threshold, representing the point at which local resources and infrastructure become insufficient to address the needs arising from the event, is a critical determinant in classifying an event as a disaster. The scale and intensity of the hazard itself, pre-existing vulnerabilities, and the community’s preparedness level all contribute to whether coping capacity is exceeded.

Consider two scenarios involving flooding. In one, a relatively small, isolated community experiences heavy rainfall leading to localized flooding. If this community possesses adequate drainage systems, emergency response protocols, and community support networks, it may be able to manage the situation effectively without external assistance. The hazard, while significant, does not exceed the community’s coping capacity and therefore does not constitute a disaster. Conversely, a larger, densely populated urban area facing a similar flooding event may find its infrastructure overwhelmed, emergency services stretched thin, and essential supplies depleted. In this scenario, the same hazard, due to the scale of the impact and the community’s specific vulnerabilities, surpasses the local capacity to cope, resulting in a natural disaster. The need for external intervention, whether from regional, national, or international bodies, becomes a defining characteristic.

The concept of exceeding coping capacity is crucial for understanding the dynamics of disasters and for informing effective disaster risk reduction strategies. Recognizing the factors that contribute to vulnerability, strengthening local capacities, and establishing robust support networks are essential for minimizing the likelihood of a hazard escalating into a disaster. Investing in resilient infrastructure, early warning systems, and community-based disaster preparedness programs can significantly enhance a community’s capacity to cope with and recover from hazardous events, ultimately reducing the human and economic costs associated with natural disasters.

5. Widespread Damage

Widespread damage serves as a key indicator differentiating a natural hazard from a natural disaster. While a hazard represents a potential threat, the extensive destruction resulting from a disaster signifies the severity of the event and the scale of its impact. Examining the facets of widespread damage provides crucial insights into the consequences of natural disasters and the need for effective mitigation and response strategies.

- Infrastructure Destruction:

Damage to critical infrastructure, including transportation networks, communication systems, power grids, and healthcare facilities, signifies a major component of widespread damage. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, for example, crippled coastal infrastructure across multiple countries, hindering rescue and relief efforts. The destruction of transportation systems isolates communities, impeding access to essential supplies and medical assistance. Damaged communication networks disrupt emergency response coordination and hinder access to vital information. The loss of power disrupts essential services, impacting hospitals, water treatment plants, and businesses.

- Property Loss:

Extensive damage to homes, businesses, and agricultural lands represents a significant economic and social consequence of natural disasters. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 caused widespread property destruction across the Gulf Coast of the United States, displacing hundreds of thousands of people and resulting in billions of dollars in economic losses. The destruction of homes leaves individuals and families without shelter, exacerbating human suffering. Damage to businesses disrupts economic activity, leading to job losses and economic hardship. Agricultural losses impact food security, potentially leading to price increases and shortages.

- Environmental Degradation:

Natural disasters can cause significant environmental damage, impacting ecosystems, water resources, and air quality. The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, while not a natural disaster, exemplifies the potential for widespread environmental degradation following a catastrophic event. Oil spills contaminate marine environments, harming wildlife and disrupting ecosystems. Floods can contaminate water supplies, spreading waterborne diseases. Wildfires release harmful pollutants into the atmosphere, impacting air quality and human health.

- Displacement and Loss of Life:

Forced displacement and loss of life represent the most tragic consequences of widespread damage. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan resulted in significant loss of life and forced the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. Displacement disrupts social networks, creates refugee crises, and places immense strain on relief organizations. The loss of life represents an immeasurable human cost and underscores the urgent need for effective disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies.

The scale of widespread damage resulting from a natural disaster directly correlates with the severity of the event and the vulnerability of the affected population. Understanding the diverse facets of this damage, from infrastructure destruction to environmental degradation, informs the development of comprehensive disaster risk reduction strategies aimed at minimizing human suffering, economic losses, and environmental impacts. By investing in resilient infrastructure, early warning systems, and community-based preparedness programs, societies can strive to mitigate the devastating consequences of natural disasters and build more resilient communities.

6. Significant Disruption

Significant disruption to societal functions and daily life represents a defining characteristic of natural disasters, distinguishing them from less impactful hazardous events. This disruption, stemming from the cascading effects of the initial hazard, permeates various aspects of society, from economic activities and essential services to social structures and individual well-being. Examining the multifaceted nature of this disruption provides critical insights for disaster preparedness, response, and recovery.

- Economic Impacts:

Natural disasters can cause significant economic disruption, impacting businesses, supply chains, and overall economic productivity. The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, for example, severely disrupted manufacturing and trade, leading to substantial economic losses both domestically and internationally. Damage to infrastructure, such as ports and transportation networks, hinders the movement of goods and services, further exacerbating economic hardship. Business closures, job losses, and reduced consumer spending contribute to the overall economic downturn following a disaster.

- Disruption of Essential Services:

Natural disasters frequently disrupt essential services, including healthcare, water supply, sanitation, and education. The 2010 Haiti earthquake devastated the country’s already fragile healthcare system, hindering access to medical care for the injured and increasing the risk of disease outbreaks. Damage to water and sanitation infrastructure can lead to waterborne illnesses and create unsanitary conditions. Disruptions to education systems interrupt children’s learning and can have long-term consequences for their development.

- Social and Psychological Impacts:

Beyond the immediate physical impacts, natural disasters can cause profound social and psychological disruption. The loss of loved ones, displacement from homes, and the experience of trauma can have lasting psychological effects on individuals and communities. Social cohesion can be disrupted, leading to increased crime rates and social unrest. The disruption of social support networks further exacerbates the challenges faced by vulnerable populations.

- Governance and Institutional Disruption:

Natural disasters can overwhelm local governance structures and disrupt institutional capacity. The 2005 Hurricane Katrina exposed weaknesses in emergency response and disaster management systems in the United States, highlighting the challenges of coordinating effective responses to large-scale events. Damage to government buildings and infrastructure can disrupt administrative functions, hindering the delivery of essential services and impeding recovery efforts.

The significant disruption caused by natural disasters underscores the interconnectedness of various societal systems and the cascading nature of their impacts. Understanding the multifaceted dimensions of this disruption, from economic impacts to social and psychological consequences, is essential for developing comprehensive disaster risk reduction strategies. By investing in resilient infrastructure, strengthening social safety nets, and enhancing institutional capacity, societies can strive to minimize disruption, facilitate recovery, and build more resilient communities in the face of future natural hazards.

7. External Assistance Required

The necessity of external assistance often distinguishes a significant natural hazard from a full-blown natural disaster. This reliance on outside aid underscores the severity of the event and the limitations of local resources in effectively addressing its consequences. When a community’s coping capacity is overwhelmed, external assistance becomes crucial for providing essential resources, facilitating recovery efforts, and mitigating further loss of life and property. This external support can take various forms, ranging from financial aid and logistical support to the deployment of specialized personnel and equipment.

The magnitude of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, for example, overwhelmed the nation’s capacity to respond effectively. The devastation necessitated substantial international assistance, including search and rescue teams, medical personnel, emergency supplies, and financial aid. Similarly, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, impacting multiple countries across a vast geographical area, required a coordinated international response to address the immense humanitarian crisis. The provision of external assistance in these instances proved critical for saving lives, providing essential services, and initiating the long and arduous recovery process. Conversely, a less severe event, even if causing localized damage, might be managed effectively with existing local resources, thus not requiring external intervention.

Understanding the threshold at which external assistance becomes necessary is crucial for effective disaster preparedness and response planning. Factors such as the scale of the event, the vulnerability of the affected population, the capacity of local infrastructure, and the availability of pre-positioned resources all contribute to determining the need for outside support. Robust disaster risk reduction strategies should encompass contingency plans for requesting and coordinating external assistance, ensuring that mechanisms are in place to facilitate a timely and effective response when local resources are insufficient. The effectiveness of external assistance hinges on pre-established partnerships, clear communication channels, and coordinated logistical arrangements. Recognizing the potential need for external intervention and integrating this understanding into disaster preparedness plans is essential for mitigating the human and economic costs of catastrophic natural events.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the distinction between natural hazards and natural disasters, aiming to provide clear and concise information.

Question 1: Does the frequency of a hazardous event influence its classification as a disaster?

While a single, high-magnitude event can certainly constitute a disaster, the cumulative impact of frequent, lower-magnitude events can also overwhelm a community’s coping capacity, leading to a disaster classification. Frequency, coupled with vulnerability, plays a significant role.

Question 2: Can human activity transform a natural hazard into a natural disaster?

Human activities, such as deforestation, urbanization, and greenhouse gas emissions, can exacerbate the impact of natural hazards, increasing vulnerability and the likelihood of an event becoming a disaster. For example, deforestation increases the risk of landslides, while urbanization intensifies the impact of flooding.

Question 3: Are all natural disasters large-scale events?

The scale of a disaster is relative to the affected community’s coping capacity. A localized event can be a disaster for a small, isolated community if it overwhelms their resources, even if the event’s geographic footprint is relatively small.

Question 4: How does climate change influence the occurrence of natural disasters?

Climate change is projected to increase the frequency and intensity of certain natural hazards, such as heatwaves, droughts, floods, and extreme weather events. This increased intensity can escalate the likelihood of these hazards exceeding communities’ coping capacities, leading to more frequent and severe disasters.

Question 5: What role does disaster preparedness play in mitigating the impact of natural hazards?

Effective disaster preparedness measures, including early warning systems, evacuation plans, and community education programs, significantly reduce vulnerability and enhance community resilience. Preparedness is crucial for minimizing the impact of hazards and preventing them from escalating into disasters.

Question 6: How does one distinguish between disaster relief and disaster preparedness?

Disaster relief focuses on immediate response efforts following a disaster, providing essential aid and support to affected communities. Disaster preparedness, conversely, involves proactive measures taken before an event occurs to minimize vulnerability and enhance resilience. Both are crucial components of comprehensive disaster risk reduction.

Understanding the complex interplay of natural processes, human vulnerability, and coping capacity is crucial for effective disaster risk reduction. Proactive measures, including preparedness planning and mitigation strategies, are essential for minimizing the impact of natural hazards and building more resilient communities.

The following section will delve into specific case studies of natural disasters, illustrating the diverse ways in which these events impact communities and the importance of effective disaster management strategies.

Conclusion

The distinction between a natural hazard and a natural disaster hinges on the intersection of a potentially harmful natural phenomenon with human vulnerability and societal coping mechanisms. This exploration has highlighted the multifaceted nature of natural hazards, encompassing geological, hydrometeorological, geomorphological, and biological processes. Furthermore, the potential for harm, influenced by magnitude, frequency, area of impact, and the vulnerability of exposed elements, dictates the severity of an event’s consequences. Exceeding local coping capacities, resulting in widespread damage, significant disruption, and the need for external assistance, signifies the transformation of a hazard into a disaster.

Mitigating the devastating impacts of these events requires a comprehensive approach encompassing proactive preparedness, robust infrastructure development, and a deep understanding of underlying vulnerabilities. The escalating risks associated with climate change underscore the urgency of enhancing global resilience and fostering a collective commitment to safeguarding communities from the escalating threat of natural disasters. Continued research, technological advancements, and international cooperation are essential for refining predictive capabilities, bolstering mitigation strategies, and fostering a future where communities not only survive but thrive in the face of natural hazards.