Defining the single most destructive natural event is complex, as “devastation” can be measured by various metrics: human casualties, economic loss, long-term environmental impact, or a combination thereof. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, floods, wildfires, droughts, and pandemics all possess the potential for widespread destruction, each exhibiting unique characteristics and consequences. For instance, a relatively low-magnitude earthquake in a densely populated area with poor infrastructure can cause more damage than a higher-magnitude quake in a remote region. Similarly, a slow-onset drought might ultimately lead to more fatalities than a sudden tsunami, though its impact unfolds over a longer period.

Understanding the potential for extreme natural events is crucial for disaster preparedness, mitigation strategies, and resource allocation. Historical analysis of these events reveals patterns and vulnerabilities that inform building codes, evacuation plans, and early warning systems. Investing in research and infrastructure aimed at predicting and mitigating the impact of these events is essential for safeguarding communities and minimizing loss of life and property. This knowledge also aids in developing sustainable practices that reduce human contribution to certain types of disasters, like those influenced by climate change.

This discussion will further examine the different types of natural disasters, exploring their specific characteristics, historical impact, and the ongoing efforts to predict and mitigate their devastating effects. This exploration will also consider the interconnectedness of these events and the cascading consequences they can trigger.

Preparing for Extreme Natural Events

Preparation is crucial for mitigating the impact of catastrophic natural events. The following tips offer guidance for enhancing individual and community resilience.

Tip 1: Understand Local Risks: Research the specific hazards prevalent in a given geographic location. Coastal regions face heightened tsunami and hurricane risks, while areas near fault lines are prone to earthquakes. Understanding these risks is the first step towards effective preparation.

Tip 2: Develop an Emergency Plan: Create a comprehensive plan that includes evacuation routes, communication protocols, and designated meeting points. This plan should account for all household members, including pets, and be regularly reviewed and practiced.

Tip 3: Assemble an Emergency Kit: Stock a kit with essential supplies such as non-perishable food, water, first-aid supplies, medications, a flashlight, a radio, and extra batteries. This kit should be readily accessible and regularly replenished.

Tip 4: Secure Property: Take steps to reinforce homes and businesses against potential damage. This might include installing storm shutters, reinforcing roofing, or anchoring furniture to prevent it from tipping over during earthquakes.

Tip 5: Stay Informed: Monitor weather reports and official alerts from local authorities. Sign up for emergency notification systems and be aware of evacuation orders.

Tip 6: Support Community Preparedness: Participate in community-level disaster preparedness initiatives. This may involve volunteering with local organizations, attending training sessions, or participating in drills.

Tip 7: Consider Insurance: Evaluate insurance policies to ensure adequate coverage against potential losses from natural disasters. Understand policy limitations and exclusions.

Proactive planning and preparation are key to navigating the aftermath of a catastrophic natural event. These measures enhance individual and community resilience, minimizing loss and facilitating recovery.

Through understanding the risks, developing robust plans, and taking preventative measures, communities can significantly reduce their vulnerability to the devastating impacts of natural disasters.

1. Magnitude

Magnitude plays a crucial role in determining the devastation caused by a natural disaster. It represents the size and intensity of the event, often quantifiable through specific scales. For earthquakes, the moment magnitude scale measures the energy released, while the Saffir-Simpson scale categorizes hurricanes based on wind speed. Volcanic eruptions are ranked using the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), reflecting the volume of ejected material. A higher magnitude typically correlates with greater potential for destruction, but the relationship is not always straightforward. The impact also depends on other factors, including population density, building codes, and pre-existing vulnerabilities.

A high-magnitude earthquake in a sparsely populated area may cause less damage than a lower-magnitude earthquake in a densely populated city with inadequate infrastructure. The 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile, the largest earthquake ever recorded (magnitude 9.5), caused significant damage and loss of life. However, the 2010 Haiti earthquake, with a lower magnitude of 7.0, resulted in a significantly higher death toll due to factors like poor building construction and higher population density in the affected area. Similarly, a Category 5 hurricane making landfall in a remote area will have a different impact than a Category 3 hurricane hitting a major metropolitan area.

Understanding the relationship between magnitude and devastation is vital for disaster preparedness and mitigation. While magnitude provides a measure of the event’s potential destructive power, it must be considered in conjunction with vulnerability factors to accurately assess risk. This understanding informs building codes, land-use planning, and the development of early warning systems. It also underscores the importance of community-level preparedness and the need for resilient infrastructure in high-risk areas. Effective risk assessment relies on combining magnitude with other relevant factors to create a more comprehensive and nuanced picture of potential impacts.

2. Mortality

Mortality, representing the loss of human life, serves as a stark measure of a natural disaster’s devastating impact. While property damage and economic losses are significant, the irreplaceable loss of life underscores the profound human cost of these events. Analyzing mortality statistics provides crucial insights for understanding disaster severity, informing public health responses, and guiding future mitigation efforts.

- Immediate vs. Long-Term Mortality

Disasters can cause both immediate deaths and fatalities that occur later due to injuries, disease outbreaks, or compromised infrastructure. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami resulted in a massive immediate loss of life, while the 2010 Haiti earthquake saw a significant number of deaths in the following weeks and months due to infections and lack of access to medical care. Distinguishing between immediate and long-term mortality provides a clearer picture of a disaster’s full impact and helps allocate resources effectively.

- Vulnerable Populations

Certain populations are disproportionately vulnerable during natural disasters. The elderly, individuals with disabilities, low-income communities, and those living in precarious housing face higher risks. The impact of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 highlighted the vulnerability of low-income communities in New Orleans. Understanding these vulnerabilities is critical for developing targeted interventions and ensuring equitable disaster response.

- Public Health Infrastructure

The robustness of a region’s public health infrastructure significantly influences mortality rates following a disaster. Access to medical care, sanitation, and clean water are essential for preventing further loss of life. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how overwhelmed healthcare systems can exacerbate mortality during a crisis. Investing in robust public health infrastructure is crucial for mitigating the long-term impacts of natural disasters.

- Data Collection and Analysis

Accurate mortality data is essential for understanding the true scale of a disaster and informing future preparedness efforts. Challenges in data collection, particularly in remote or severely affected areas, can hinder accurate assessment. Improved data collection methodologies and post-disaster assessments are crucial for learning from past events and enhancing future response strategies.

Mortality serves as a critical indicator of devastation, reflecting the human cost of natural disasters. By analyzing mortality data, considering the specific vulnerabilities of different populations, and strengthening public health infrastructure, societies can work toward reducing the loss of life in future events. A comprehensive understanding of mortality patterns and contributing factors is essential for developing effective disaster mitigation and response strategies.

3. Economic Loss

Economic loss represents a significant dimension of devastation following a natural disaster. Beyond the immediate physical damage, these events trigger cascading economic consequences that can cripple communities and regions for years. Understanding the multifaceted nature of economic loss is crucial for developing effective recovery strategies and mitigating future impacts.

- Direct Costs

Direct costs encompass the immediate physical damage to infrastructure, property, and assets. This includes destroyed homes, businesses, transportation networks, and agricultural lands. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan caused unprecedented direct costs, estimated at hundreds of billions of dollars, due to widespread destruction of coastal cities and industrial facilities. Accurately assessing direct costs is crucial for insurance claims, government aid, and rebuilding efforts.

- Indirect Costs

Indirect costs represent the economic ripple effects of a disaster, impacting businesses, supply chains, and overall productivity. Business interruptions, loss of tourism revenue, and disruptions to transportation networks contribute significantly to indirect costs. The 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajkull in Iceland, while causing relatively little direct physical damage, triggered widespread disruption to air travel across Europe, resulting in substantial economic losses for airlines and related industries. Quantifying indirect costs can be challenging but is vital for understanding the full economic impact.

- Long-Term Economic Impacts

Long-term economic impacts extend beyond the immediate aftermath, affecting regional development and long-term economic growth. Disruptions to industries, population displacement, and damage to agricultural lands can have lasting economic consequences. The 1995 Kobe earthquake in Japan had long-term impacts on the region’s manufacturing sector, demonstrating the need for long-term recovery planning and economic diversification to enhance resilience.

- Economic Disparity and Recovery

Natural disasters often exacerbate existing economic inequalities, disproportionately impacting vulnerable populations and hindering their ability to recover. Lower-income communities may lack the resources to rebuild or relocate, widening the economic gap. Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans highlighted the vulnerability of low-income communities and the challenges they face in recovering from such events. Addressing economic disparities is crucial for ensuring equitable disaster recovery and building community resilience.

Economic loss forms a critical component in assessing the devastation wrought by natural disasters. By understanding the interplay of direct costs, indirect costs, long-term impacts, and the exacerbation of economic disparities, effective strategies can be developed for disaster recovery, economic resilience, and sustainable development in vulnerable regions. The economic consequences of these events underscore the need for comprehensive planning, insurance mechanisms, and targeted support for affected communities, particularly those most vulnerable to economic hardship.

4. Long-term impact

Long-term impact constitutes a critical factor in evaluating the devastation of natural disasters, extending far beyond immediate aftermath. While initial mortality and economic losses are readily apparent, the enduring consequences shape communities and ecosystems for years, even decades. Understanding these long-term impacts is crucial for developing comprehensive recovery strategies, mitigating future risks, and fostering resilient communities.

Several factors contribute to the long-term impact of a disaster. Environmental degradation, such as soil erosion and water contamination following floods or wildfires, can lead to lasting ecological damage and agricultural losses. Disruptions to essential services, like healthcare and education, impede societal recovery and can have profound impacts on human development. Psychological trauma experienced by survivors can persist for years, requiring long-term mental health support. Displacement and migration, often resulting from large-scale disasters, create social and economic challenges for both affected populations and host communities. The Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986 exemplifies the enduring impact of environmental contamination, impacting human health and the surrounding ecosystem for decades.

The practical significance of understanding long-term impacts is substantial. Effective disaster recovery strategies must address not only immediate needs but also the protracted challenges that hinder long-term recovery. Investment in resilient infrastructure, mental health services, and sustainable environmental management are crucial for minimizing long-term consequences. Furthermore, analyzing the long-term impacts of past disasters informs future risk assessments and mitigation strategies. The ongoing recovery efforts following Hurricane Katrina in 2005 offer valuable lessons in addressing long-term social, economic, and environmental challenges. Recognizing the complexity and duration of these impacts is essential for building more resilient communities and mitigating the devastating legacy of natural disasters.

5. Geographic Scope

Geographic scope significantly influences the devastation wrought by natural disasters. A localized event, like a landslide, can cause significant destruction within a limited area, while widespread events, such as pandemics or large-scale droughts, can have far-reaching consequences across vast regions or even globally. The spatial extent of a disaster’s impact determines the scale of response required, the resources needed for recovery, and the long-term consequences for affected populations and ecosystems. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, triggered by a massive earthquake, impacted coastlines across multiple countries, demonstrating the far-reaching consequences of geographically widespread events. Conversely, the 1999 zmit earthquake in Turkey, while devastating within a specific region, had a more localized geographic scope.

The geographic scope of a disaster influences its impact in several crucial ways. Larger-scale events often require greater coordination of resources and international aid. Widespread disasters can disrupt global supply chains and have cascading economic effects far beyond the directly impacted areas. The geographic distribution of affected populations also influences the challenges of providing aid and supporting long-term recovery. Furthermore, the geographic characteristics of the affected region, such as topography and proximity to coastlines, can influence the specific types of hazards faced and the severity of their impacts. The spatial distribution of infrastructure and population density within the affected area also play a role in determining the extent of the damage and the effectiveness of response efforts. Understanding the interplay of these geographic factors is essential for developing effective disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies.

The practical implications of understanding geographic scope are substantial. Effective disaster planning requires accurate assessments of potential hazard zones and the identification of vulnerable populations. Geographic information systems (GIS) and remote sensing technologies play a crucial role in mapping disaster-prone areas, monitoring events as they unfold, and coordinating response efforts. Furthermore, understanding the geographic scope of past disasters informs risk assessments, land-use planning, and the development of early warning systems. By analyzing the spatial distribution of impacts, vulnerabilities, and resources, communities can better prepare for future events and mitigate the devastating consequences of natural disasters across different geographic scales.

6. Social Disruption

Social disruption represents a significant consequence of devastating natural disasters, often exceeding the immediate physical damage in its long-term impact. The breakdown of social structures, norms, and community cohesion can hinder recovery efforts and create lasting challenges for affected populations. Examining the various facets of social disruption provides crucial insights into the multifaceted impacts of these events and informs strategies for building more resilient communities.

- Displacement and Migration

Forced displacement and migration are common consequences of large-scale disasters, creating social and economic challenges for both displaced populations and host communities. Loss of homes and livelihoods can lead to mass migrations, straining resources and potentially exacerbating existing social tensions. The 2010 Haiti earthquake resulted in significant internal displacement, highlighting the challenges of providing adequate shelter, sanitation, and social services to displaced populations. Understanding the dynamics of displacement and migration is crucial for planning effective disaster response and supporting long-term resettlement and reintegration efforts.

- Loss of Social Support Networks

Natural disasters can fracture social support networks, leaving individuals and families without crucial resources and emotional support. The destruction of community centers, places of worship, and other social gathering spaces further isolates individuals and hinders community rebuilding. The disruption of communication networks can also impede access to information and support services. Recognizing the importance of social support networks is crucial for developing community-based recovery programs and providing psychosocial support to affected populations.

- Increased Social Inequality

Natural disasters often exacerbate existing social inequalities, disproportionately impacting vulnerable populations. Marginalized communities may lack access to essential resources, healthcare, and information, increasing their vulnerability to the impacts of disasters. The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 revealed the stark disparities in access to resources and support between different communities in New Orleans. Addressing these pre-existing inequalities is essential for ensuring equitable disaster response and promoting inclusive recovery processes.

- Psychological Trauma and Mental Health

The psychological trauma experienced by disaster survivors can have long-lasting impacts on mental health and well-being. Experiencing loss, displacement, and the disruption of daily life can contribute to anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other mental health challenges. Providing access to mental health services and psychosocial support is crucial for fostering individual and community recovery. The psychological impact of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan highlighted the need for long-term mental health support for survivors.

The multifaceted nature of social disruption underscores the complexity of disaster impacts, extending far beyond immediate physical damage. By understanding the interplay of displacement, loss of social support, increased inequality, and psychological trauma, more effective strategies can be developed for fostering community resilience, supporting long-term recovery, and mitigating the profound social consequences of devastating natural disasters. Recognizing the interconnectedness of these social factors with other dimensions of disaster impact, such as economic loss and environmental degradation, is essential for building more resilient and equitable communities in the face of future events.

Frequently Asked Questions about Devastating Natural Disasters

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the assessment and impact of devastating natural events.

Question 1: How is the “most devastating” natural disaster determined?

Defining “most devastating” requires considering multiple factors, including magnitude, mortality, economic impact, long-term consequences, geographic scope, and social disruption. No single metric definitively determines the “worst” disaster.

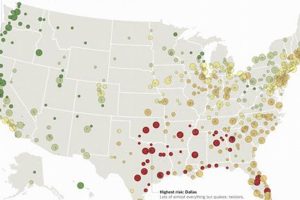

Question 2: Are certain regions more susceptible to specific types of disasters?

Geographic location significantly influences disaster risk. Coastal regions are more vulnerable to tsunamis and hurricanes, while areas near fault lines are prone to earthquakes. Understanding regional vulnerabilities is crucial for targeted preparedness efforts.

Question 3: Does climate change influence the frequency or intensity of natural disasters?

Scientific evidence suggests that climate change is altering weather patterns and increasing the intensity and frequency of certain extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, floods, and droughts.

Question 4: What measures can be taken to mitigate the impact of natural disasters?

Mitigation strategies include developing early warning systems, strengthening building codes, implementing land-use planning policies, investing in resilient infrastructure, and promoting community-level preparedness.

Question 5: How can individuals contribute to disaster preparedness?

Individuals can develop personal emergency plans, assemble emergency kits, participate in community drills, and stay informed about potential hazards and official alerts.

Question 6: What role does international cooperation play in disaster response and recovery?

International cooperation is crucial for sharing resources, providing technical assistance, and coordinating aid distribution following large-scale disasters that transcend national borders.

Preparedness, mitigation, and international cooperation are vital for minimizing the devastation caused by natural disasters and fostering more resilient communities.

The following sections will further explore specific disaster types and delve into the science behind their occurrence and impact.

What is the Most Devastating Natural Disaster

Determining the single most devastating natural disaster remains a complex question, dependent on the specific metrics used for evaluation. This exploration has highlighted the multifaceted nature of disaster impacts, encompassing magnitude, mortality, economic loss, long-term consequences, geographic scope, and social disruption. While high-magnitude events like mega-earthquakes and intense hurricanes possess immense destructive potential, other hazards, such as pandemics and widespread droughts, can inflict equally devastating consequences through different mechanisms and timelines. Understanding the diverse impacts of various natural hazards is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies and building community resilience.

Continued research into the causes, dynamics, and impacts of natural disasters remains critical for enhancing predictive capabilities and developing targeted interventions. Investing in resilient infrastructure, strengthening social safety nets, and promoting international cooperation are essential steps toward mitigating the devastating consequences of these events. Ultimately, fostering a global culture of preparedness and proactive adaptation is paramount in navigating the inevitable challenges posed by natural hazards and building a more secure and sustainable future.