The decision to reconstruct communities following a natural disaster involves a complex evaluation of competing factors. This process requires careful consideration of the economic, social, and environmental impacts of both rebuilding and relocating. For example, rebuilding a coastal town after a hurricane might involve weighing the economic benefits of restoring tourism against the potential risks of future storms and the environmental costs of reinforcing infrastructure.

Evaluating these competing factors is crucial for long-term community resilience and sustainability. Historically, societies have often chosen to rebuild in disaster-prone areas due to economic dependencies, cultural attachments, or a lack of viable alternatives. However, modern approaches increasingly emphasize incorporating disaster mitigation strategies into reconstruction plans to minimize future risks and promote sustainable development. Understanding the long-term implications of these decisions is fundamental for policymakers, urban planners, and communities alike.

The following sections will explore the multifaceted arguments for and against reconstruction in greater detail, examining the economic implications, environmental considerations, social ramifications, and the crucial role of preemptive planning and mitigation.

Tips for Evaluating Reconstruction After Natural Disasters

Careful consideration of various factors is essential when deciding whether to rebuild a community after a natural disaster. These tips provide a framework for navigating this complex process.

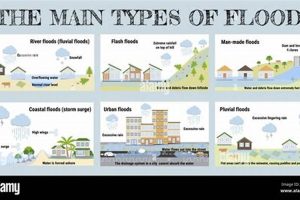

Tip 1: Conduct a thorough risk assessment. Evaluate the likelihood and potential impact of future disasters. Consider historical data, geological factors, climate change projections, and the effectiveness of potential mitigation measures.

Tip 2: Analyze the economic viability of rebuilding. Assess the costs of reconstruction, including infrastructure repair, housing, and business recovery. Compare these costs with the long-term economic benefits of rebuilding versus relocating.

Tip 3: Consider the social impacts on the community. Evaluate the effects on displacement, community cohesion, access to essential services, and cultural heritage. Prioritize community engagement and address potential social vulnerabilities.

Tip 4: Evaluate the environmental consequences. Assess the impact of reconstruction on ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural resources. Explore sustainable building practices and prioritize environmental protection and restoration.

Tip 5: Incorporate disaster mitigation strategies. Integrate building codes, land-use planning, and infrastructure design that enhance resilience to future disasters. Implement early warning systems and evacuation plans.

Tip 6: Explore alternative development pathways. Consider options such as managed retreat, relocation, or adaptation strategies that minimize future risk. Evaluate the feasibility and implications of each alternative.

Tip 7: Secure diverse funding sources. Explore a combination of public and private funding mechanisms, including insurance payouts, government grants, and philanthropic contributions, to ensure adequate financial resources for long-term recovery.

By carefully considering these factors, decision-makers can promote sustainable and resilient community recovery following natural disasters.

These tips offer a starting point for the crucial process of post-disaster decision-making. The next section will delve into specific case studies illustrating these principles in action.

1. Economic Recovery

Economic recovery forms a central component in evaluating the merits of post-disaster reconstruction. The injection of funds for rebuilding stimulates local economies, creating jobs in construction, manufacturing, and related service sectors. This influx of economic activity can revitalize affected areas, generating revenue and restoring livelihoods. However, the scale of investment required can be substantial, often exceeding pre-disaster levels. For example, following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan, the cost of reconstruction was estimated at over $200 billion. Furthermore, economic recovery can be unevenly distributed, benefiting some sectors more than others, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities.

The decision to rebuild versus relocate businesses and industries involves weighing the potential for long-term economic growth against the risks of future disasters. Rebuilding in the same location might maintain established supply chains and customer bases, but also exposes businesses to repeated losses. Relocating, on the other hand, while potentially mitigating future risks, disrupts established economic networks and requires significant new investment. The choice must consider factors such as industry-specific vulnerabilities, insurance coverage, and government incentives. For instance, after Hurricane Katrina, some businesses in New Orleans relocated to higher ground or other cities, while others chose to rebuild in the same location, often incorporating flood mitigation measures.

Successful economic recovery after a natural disaster necessitates balancing short-term stimulus with long-term sustainability. Investment in resilient infrastructure, diversification of local economies, and supportive policies for businesses are crucial for achieving sustained growth. Challenges include securing adequate funding, managing competing demands for resources, and ensuring equitable distribution of benefits. Understanding the complex interplay of these factors is essential for informed decision-making and building more resilient communities.

2. Infrastructure Resilience

Infrastructure resilience plays a critical role in the complex calculus of post-disaster rebuilding. Resilient infrastructure, designed to withstand and recover from natural hazards, minimizes disruption to essential services such as power, water, and transportation. This reduces economic losses, facilitates quicker community recovery, and enhances overall societal well-being. Investing in resilient infrastructure during reconstruction, while often more expensive initially, offers long-term cost savings by reducing the need for repeated repairs and replacements. For instance, burying power lines underground, though a significant upfront investment, mitigates the risk of widespread power outages caused by downed lines during storms. Similarly, constructing buildings to updated seismic codes minimizes damage from earthquakes, reducing the need for costly repairs or demolition.

However, achieving infrastructure resilience presents significant challenges. Balancing the costs of enhanced resilience against budgetary constraints requires careful prioritization. Decisions must be made regarding which infrastructure systems to prioritize and the level of protection to implement. For example, coastal communities might prioritize strengthening seawalls and elevating critical infrastructure, while inland areas may focus on flood control measures and earthquake-resistant construction. Furthermore, technological advancements and evolving understanding of natural hazards necessitate ongoing adaptation and investment. Building codes and design standards must be regularly updated to reflect the latest scientific knowledge and engineering practices. The development of new materials and construction techniques also offers opportunities to enhance resilience further.

Understanding the trade-offs between initial investment costs and long-term benefits is crucial for effective decision-making regarding infrastructure resilience. Life-cycle cost analysis, which considers both upfront construction costs and ongoing maintenance and repair expenses, provides a valuable tool for evaluating different resilience strategies. Furthermore, integrating infrastructure resilience into broader community planning efforts ensures a holistic approach to disaster preparedness and recovery. This includes land-use planning, zoning regulations, and building codes that minimize exposure to natural hazards. By prioritizing infrastructure resilience, communities can minimize the devastating impacts of future disasters and foster sustainable development.

3. Community restoration

Community restoration represents a complex and multifaceted aspect of post-disaster rebuilding, encompassing the social fabric, cultural heritage, and psychological well-being of affected populations. While physical reconstruction addresses the tangible damage to infrastructure and buildings, community restoration focuses on the less tangible but equally crucial process of rebuilding social networks, restoring cultural identity, and addressing the psychological impacts of disaster.

- Social Cohesion

Disasters can disrupt social networks and displace residents, fracturing community bonds. Post-disaster rebuilding efforts must prioritize fostering social cohesion through community centers, public spaces, and initiatives that promote interaction and mutual support. For example, after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, community-led recovery efforts played a vital role in rebuilding social connections and providing psychosocial support. However, rebuilding social cohesion can be challenging, particularly in diverse communities where pre-existing social inequalities may be exacerbated by disaster impacts.

- Cultural Heritage

Natural disasters can destroy historical landmarks, cultural institutions, and traditional practices, leading to a loss of collective identity. Preserving and restoring cultural heritage during the rebuilding process is essential for maintaining community identity and fostering a sense of continuity. For instance, the reconstruction of historic buildings and monuments after the 1995 Kobe earthquake in Japan symbolized resilience and cultural continuity. However, decisions about which aspects of cultural heritage to prioritize for restoration can be contentious, involving complex trade-offs between historical preservation and economic development.

- Psychological Well-being

Disasters can inflict profound psychological trauma, leading to anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Addressing the mental health needs of affected populations is a critical component of community restoration. Providing access to mental health services, fostering social support networks, and creating opportunities for collective healing are crucial for promoting psychological recovery. However, mental health needs often go unmet after disasters due to limited resources, stigma, and a lack of awareness.

- Governance and Participation

Effective community restoration requires inclusive governance structures that empower residents to participate in the rebuilding process. Engaging local communities in decision-making ensures that reconstruction efforts address their specific needs and priorities. For example, participatory planning processes can incorporate community input on housing design, land use, and infrastructure development. However, balancing diverse interests and ensuring equitable participation can be challenging, requiring strong leadership and effective communication strategies.

These facets of community restoration are intricately intertwined and essential for achieving comprehensive recovery after a natural disaster. Successful rebuilding requires not only repairing physical damage but also addressing the social, cultural, and psychological impacts, fostering resilient and cohesive communities for the future. The long-term success of reconstruction efforts ultimately hinges on the extent to which they promote community well-being and empower residents to shape their own recovery.

4. Environmental Impact

Environmental impact represents a crucial dimension within the complex evaluation of post-disaster rebuilding. Reconstruction activities themselves generate environmental consequences, including increased carbon emissions from manufacturing building materials and operating construction equipment, as well as potential impacts on local ecosystems through habitat disruption and waste generation. Conversely, rebuilding offers opportunities to integrate sustainable building practices, promoting energy efficiency, reducing reliance on fossil fuels, and minimizing long-term environmental footprints. For instance, incorporating green building standards in reconstruction can lead to more energy-efficient structures, reducing future greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, rebuilding can incorporate nature-based solutions, such as restoring coastal wetlands to provide natural buffers against future storms, demonstrating the potential for positive environmental outcomes.

The choice between rebuilding and managed retreat carries profound environmental implications. Managed retreat, involving the relocation of communities away from hazard-prone areas, can reduce human impact on vulnerable ecosystems, allowing for natural restoration processes. For example, retreating from eroding coastlines can reduce habitat destruction and allow for the natural migration of coastal ecosystems inland. However, managed retreat can also have unintended consequences, such as increased development pressure on other areas, potentially displacing existing communities or impacting other environmentally sensitive locations. Conversely, rebuilding in situ, while potentially preserving existing communities and economic activities, may exacerbate environmental pressures on already stressed ecosystems. Careful consideration of these trade-offs is essential for informed decision-making.

Integrating environmental considerations into post-disaster rebuilding necessitates a comprehensive assessment of both short-term and long-term impacts. This includes evaluating the environmental footprint of construction activities, promoting sustainable building practices, incorporating nature-based solutions, and considering the long-term ecological implications of different rebuilding strategies. Understanding the complex interplay between human development and environmental sustainability is paramount for fostering resilient and ecologically sound recovery efforts. Balancing the need for rapid reconstruction with the imperative for long-term environmental stewardship remains a significant challenge in post-disaster contexts, demanding innovative approaches and careful planning to minimize negative impacts and maximize opportunities for environmental enhancement.

5. Psychological well-being

Psychological well-being constitutes a crucial, yet often overlooked, dimension of post-disaster recovery. The impacts of natural disasters extend far beyond physical damage, profoundly affecting the mental and emotional health of individuals and communities. Understanding the psychological consequences of disasters and incorporating mental health considerations into rebuilding strategies is essential for fostering comprehensive and sustainable recovery.

- Trauma and Loss

Experiencing a natural disaster can inflict profound psychological trauma. Loss of life, homes, and livelihoods can lead to grief, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The severity of trauma often correlates with the magnitude of the disaster and the extent of personal loss. For example, survivors of Hurricane Katrina experienced high rates of PTSD and other mental health disorders. Addressing trauma and loss requires providing access to mental health services, including counseling, therapy, and psychosocial support. Failing to address these needs can impede long-term recovery and create lasting psychological scars.

- Community Resilience and Social Support

Strong social support networks play a vital role in mitigating the psychological impacts of disasters. Community cohesion and social connections provide a sense of belonging, shared experience, and mutual support, fostering resilience in the face of adversity. Post-disaster rebuilding efforts should prioritize strengthening community bonds through community centers, support groups, and shared activities. For instance, community-based recovery programs after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan emphasized social support and collective healing. However, disasters can also disrupt social networks, requiring deliberate efforts to rebuild social connections.

- Displacement and Relocation

Displacement following a natural disaster can exacerbate psychological distress. Loss of familiar surroundings, social networks, and routines can create feelings of insecurity, isolation, and disorientation. Relocation, whether temporary or permanent, presents further challenges, requiring adaptation to new environments and social contexts. For example, individuals displaced by Hurricane Katrina faced significant challenges integrating into new communities. Supporting displaced populations requires providing access to housing, employment, and social services, as well as fostering a sense of belonging in new communities.

- Long-Term Mental Health Impacts

The psychological impacts of natural disasters can persist long after the immediate crisis has passed. Mental health challenges, such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression, can have long-term consequences for individuals and communities, affecting physical health, social functioning, and economic well-being. Ongoing access to mental health services, community support programs, and monitoring of psychological well-being are essential for mitigating the long-term impacts of disasters. For instance, longitudinal studies of disaster survivors have shown that mental health needs can persist for years, requiring sustained support and resources.

These psychological dimensions are integral to understanding the complex interplay of factors influencing post-disaster rebuilding decisions. While economic considerations and infrastructure resilience are crucial, prioritizing psychological well-being is essential for fostering truly sustainable and equitable recovery. Ignoring the psychological needs of affected populations can impede long-term recovery, exacerbate existing inequalities, and create lasting psychological scars. Integrating mental health considerations into every stage of the rebuilding process, from immediate relief efforts to long-term community development, is crucial for building more resilient and compassionate communities in the aftermath of disaster.

6. Future Risk Mitigation

Future risk mitigation forms an integral part of the complex decision-making process regarding post-disaster rebuilding. Evaluating the potential for future hazards and implementing strategies to reduce vulnerability is crucial for ensuring the long-term sustainability and resilience of reconstructed communities. Mitigation measures influence the cost-benefit analysis of rebuilding, impacting both the economic feasibility and the social and environmental consequences of reconstruction. Careful consideration of future risks informs decisions regarding building codes, land-use planning, infrastructure design, and community preparedness.

- Building Codes and Standards

Updated building codes and standards represent a critical tool for mitigating future risks. Codes that incorporate lessons learned from past disasters, reflecting the latest scientific understanding of natural hazards and engineering best practices, enhance the resilience of new construction. For example, post-disaster revisions to building codes often mandate stronger structural components, improved wind resistance, and elevated foundations in flood-prone areas. However, enforcing updated codes can be challenging, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Furthermore, balancing the increased cost of construction with affordability remains a key consideration.

- Land-Use Planning and Zoning

Land-use planning and zoning regulations play a significant role in minimizing future vulnerability. Restricting development in high-hazard zones, such as floodplains and coastal areas, reduces exposure to future disasters. Implementing zoning regulations that promote green infrastructure, such as parks and wetlands, can provide natural buffers against floods and storm surges. However, land-use restrictions can face opposition from landowners and developers, requiring careful balancing of competing interests. Furthermore, effective land-use planning necessitates accurate hazard mapping and comprehensive risk assessments.

- Infrastructure Design and Investment

Investing in resilient infrastructure is essential for mitigating future risks. Designing and constructing infrastructure systems that can withstand and recover from natural hazards minimizes disruption to essential services and reduces economic losses. For example, burying power lines underground protects them from damage during storms, while constructing elevated roadways minimizes flood impacts. However, the upfront costs of resilient infrastructure can be substantial, requiring careful prioritization of investments. Life-cycle cost analysis, considering both initial construction costs and long-term maintenance expenses, provides a valuable framework for evaluating infrastructure investment decisions.

- Community Preparedness and Early Warning Systems

Enhancing community preparedness and establishing effective early warning systems are crucial components of future risk mitigation. Educating residents about disaster preparedness, developing evacuation plans, and establishing early warning systems for impending hazards can significantly reduce casualties and property damage. For instance, communities prone to tsunamis benefit from early warning systems that provide timely alerts, enabling residents to evacuate to higher ground. However, effective community preparedness requires ongoing investment in public education, communication infrastructure, and emergency response capacity.

These facets of future risk mitigation are interconnected and essential for ensuring the long-term success of post-disaster rebuilding efforts. Integrating mitigation measures into reconstruction planning, building codes, and community development strategies enhances resilience, reduces vulnerability, and promotes sustainable development. By carefully considering future risks, communities can minimize the devastating impacts of natural hazards, creating safer, more resilient, and prosperous futures. The long-term benefits of incorporating these mitigation strategies far outweigh the initial costs, contributing significantly to the overall positive assessment when weighing the pros and cons of rebuilding.

Frequently Asked Questions about Rebuilding After Natural Disasters

Addressing common concerns regarding post-disaster reconstruction is crucial for informed decision-making. The following FAQs provide insights into key considerations.

Question 1: What are the primary economic considerations when deciding whether to rebuild after a natural disaster?

Economic considerations encompass evaluating the costs of reconstruction, including infrastructure repair, housing, business recovery, and the potential for long-term economic growth. Factors such as insurance coverage, government aid, and the availability of private investment influence the economic feasibility of rebuilding.

Question 2: How does environmental impact factor into the decision to rebuild?

Environmental impact assessments evaluate the potential consequences of reconstruction on ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural resources. Sustainable building practices, nature-based solutions, and the long-term ecological implications of different rebuilding strategies are key considerations.

Question 3: What are the key social and community challenges associated with rebuilding after a disaster?

Social and community challenges include addressing displacement, fostering social cohesion, restoring cultural heritage, providing access to essential services, and promoting psychological well-being among affected populations.

Question 4: How can future risks be mitigated in the rebuilding process?

Future risk mitigation involves incorporating updated building codes, land-use planning, resilient infrastructure design, early warning systems, and community preparedness measures to reduce vulnerability to future hazards.

Question 5: What are the alternatives to rebuilding in the same location after a disaster?

Alternatives to rebuilding in situ include managed retreat, relocation to less hazard-prone areas, and adaptation strategies that minimize future risk. The feasibility and implications of each alternative must be carefully evaluated.

Question 6: What role does community participation play in successful post-disaster reconstruction?

Community participation is essential for ensuring that rebuilding efforts address the specific needs and priorities of affected populations. Engaging residents in decision-making processes fosters ownership, promotes social cohesion, and contributes to more equitable and sustainable outcomes.

Careful consideration of these factors contributes significantly to informed decision-making regarding post-disaster reconstruction, promoting resilient and sustainable community recovery.

Further exploration of specific case studies illustrating these principles will follow in the next section.

Conclusion

Decisions regarding post-disaster reconstruction present complex challenges, demanding careful evaluation of competing factors. Balancing economic recovery with environmental protection, social equity with infrastructure resilience, and present needs with future risks requires a multifaceted approach. Effective reconstruction necessitates integrating sustainable building practices, mitigating future hazards, and fostering community participation throughout the decision-making process. The exploration of economic implications, environmental considerations, social ramifications, infrastructure resilience, psychological well-being, and future risk mitigation underscores the multifaceted nature of this critical undertaking. Careful consideration of these factors is essential for informed decision-making and the creation of resilient, sustainable communities.

Sustainable and equitable reconstruction requires a long-term perspective, recognizing that the impacts of natural disasters extend far beyond the immediate aftermath. Investing in resilient infrastructure, promoting sustainable development practices, and empowering communities to shape their own recovery are crucial for building a more resilient and equitable future. The choices made in the wake of disaster will shape communities for generations to come, underscoring the profound significance of informed and compassionate decision-making.