Defining the most destructive natural event in United States history requires considering various factors, including loss of life, economic impact, and long-term consequences. While individual events may hold the record for a specific metric (e.g., highest death toll, greatest financial damage), pinpointing a single, universally recognized “biggest” disaster is complex. For example, the 1900 Galveston Hurricane resulted in an immense loss of life, while Hurricane Katrina in 2005 caused catastrophic damage and displacement across a wider region, resulting in profound economic and social disruption. The long-term effects of events like the Dust Bowl of the 1930s significantly altered agricultural practices and population distribution. These diverse impacts make direct comparisons challenging.

Understanding the impact of large-scale natural events is crucial for disaster preparedness and mitigation efforts. Studying past catastrophes provides valuable insights into vulnerability, infrastructure resilience, and the effectiveness of response strategies. This knowledge is essential for developing building codes, evacuation plans, and resource allocation strategies to minimize future losses and improve community resilience. Historical context illuminates the evolving relationship between human settlements and the natural environment, emphasizing the need for sustainable practices and adaptation to changing environmental conditions.

This exploration will delve into several major natural disasters that have shaped the United States, examining their causes, consequences, and the lessons learned. Specific cases will be analyzed to demonstrate the multifaceted nature of disaster impact and highlight the ongoing efforts to mitigate risks and enhance societal preparedness.

Preparedness and Mitigation Strategies

Learning from the most devastating natural events in U.S. history provides invaluable insights for enhancing community resilience and individual preparedness. The following strategies offer guidance for mitigating risks and improving outcomes in the face of future disasters.

Tip 1: Understand Local Hazards: Research the specific natural hazards prevalent in one’s geographic area. This knowledge informs appropriate preparedness measures, such as earthquake-resistant construction in seismic zones or flood insurance in flood-prone regions.

Tip 2: Develop an Emergency Plan: Create a comprehensive family emergency plan that includes evacuation routes, communication protocols, and designated meeting points. Regularly practice the plan to ensure familiarity and effectiveness.

Tip 3: Assemble an Emergency Kit: Prepare a well-stocked emergency kit containing essential supplies like water, non-perishable food, first-aid supplies, medications, and a battery-powered radio. Ensure the kit is readily accessible and periodically check and replenish its contents.

Tip 4: Secure Property and Belongings: Take steps to protect homes and property from potential damage. This may involve reinforcing structures, trimming trees near buildings, and securing loose objects that could become projectiles in high winds.

Tip 5: Stay Informed: Monitor weather reports and official alerts from local authorities. Sign up for emergency notification systems to receive timely updates on evolving threats and recommended actions.

Tip 6: Support Community Resilience: Engage in community-level preparedness initiatives. Participate in local emergency drills, volunteer with disaster relief organizations, and advocate for policies that enhance community-wide resilience.

Tip 7: Learn Basic First Aid and CPR: Acquiring basic first aid and CPR skills empowers individuals to provide immediate assistance to injured persons in the aftermath of a disaster, potentially saving lives before professional help arrives.

Implementing these preparedness measures significantly enhances individual and community safety, minimizing vulnerability and fostering a culture of proactive disaster management. Preparedness translates to reduced losses and improved recovery outcomes when natural hazards inevitably strike.

By reflecting on the lessons learned from past disasters and adopting proactive mitigation strategies, communities can build a more resilient future, better equipped to withstand the inevitable challenges posed by natural events.

1. Magnitude

Magnitude, representing the size and intensity of a natural disaster, plays a crucial role in determining its overall impact and its potential classification as a historically significant event. Understanding the various facets of magnitude provides valuable insights into the destructive potential of these phenomena.

- Physical Measurement Scales:

Magnitude is often quantified using specific measurement scales tailored to the type of disaster. The Richter scale quantifies earthquake magnitude based on seismic wave amplitude, while the Saffir-Simpson scale categorizes hurricane intensity based on wind speed. Volcanic eruptions are measured using the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), which considers factors like eruption plume height and ejected material volume. These scales provide a standardized framework for comparing events and assessing their potential for destruction.

- Energy Released:

Magnitude is inherently linked to the amount of energy released during a natural disaster. Larger magnitude events unleash significantly more energy, resulting in greater destructive potential. The energy released during an earthquake, for example, can cause ground shaking, landslides, and tsunamis. The immense energy of a hurricane fuels powerful winds and storm surges. Understanding the relationship between magnitude and energy release helps to predict the potential consequences of these events.

- Area Affected:

While not directly a component of magnitude scales themselves, the area affected by a disaster is often correlated with its magnitude. Higher magnitude events tend to impact wider geographic areas. A large earthquake can cause damage over hundreds of square kilometers, while a powerful hurricane can affect entire coastlines. The spatial extent of the impact influences the number of people affected and the overall societal disruption caused by the disaster.

- Impact Duration:

The duration of a disaster’s impact can also be related to its magnitude. While some events, like earthquakes, are relatively short-lived, their after-effects, such as aftershocks and infrastructure damage, can persist for extended periods. Large hurricanes can linger for days, causing prolonged periods of heavy rainfall, flooding, and high winds. The duration of the impact contributes to the cumulative damage and challenges associated with response and recovery efforts.

By analyzing magnitude across these different facets, a more comprehensive understanding of a disaster’s impact can be achieved. This contributes to a more nuanced assessment when considering which events hold the unfortunate distinction of being among the “biggest” natural disasters in US history, not just in terms of immediate devastation, but also in their lasting consequences and broader societal implications.

2. Mortality

Mortality, representing the loss of human life, serves as a stark and poignant metric when assessing the impact of natural disasters. Within the context of the “biggest” natural disasters in US history, mortality figures often play a significant role in shaping public perception and historical memory. Examining the causes and consequences of high mortality rates in these events provides crucial insights for disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies. The Galveston Hurricane of 1900, with an estimated death toll between 6,000 and 12,000, stands as a grim example of the devastating potential of natural forces. The high mortality in this event resulted from a combination of factors, including the storm’s intensity, the low-lying geography of Galveston Island, and the limited warning systems available at the time. This catastrophe underscored the vulnerability of coastal communities and the urgent need for improved forecasting and evacuation procedures.

The Johnstown Flood of 1889 provides another sobering case study. The collapse of the South Fork Dam unleashed a torrent of water that claimed over 2,200 lives. This tragedy highlighted the dangers of inadequate infrastructure maintenance and the potential for cascading failures in complex systems. More recent events, such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005, while resulting in lower mortality than the Galveston Hurricane, exposed vulnerabilities in evacuation planning and emergency response systems, particularly for marginalized and vulnerable populations. Analyzing mortality data reveals disparities in impact, emphasizing the need for equitable disaster preparedness strategies that address the specific needs of diverse communities.

Understanding the factors contributing to high mortality in past disasters informs present-day mitigation efforts. Improved building codes, early warning systems, and robust evacuation plans demonstrably reduce loss of life in subsequent events. The development of tsunami warning systems following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami exemplifies the practical application of lessons learned from tragic events. While mortality remains a difficult and sensitive aspect of disaster analysis, its careful consideration provides invaluable insights for enhancing community resilience and safeguarding lives in the face of future natural hazards. Reducing mortality remains a paramount objective in disaster management, underscoring the ongoing efforts to improve preparedness, response, and recovery strategies.

3. Economic Impact

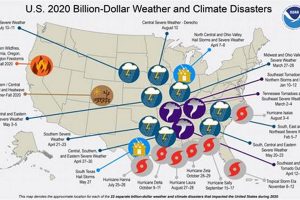

Economic impact serves as a critical measure of the devastation wrought by natural disasters, often playing a decisive role in classifying an event among the “biggest” in US history. This impact extends far beyond immediate damages, encompassing long-term disruptions to economic activity, infrastructure, and community well-being. Understanding the multifaceted nature of economic consequences is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies and fostering resilient recovery processes.

Direct costs, such as property damage and infrastructure repair, represent a significant portion of the economic burden. Hurricane Katrina, for example, inflicted unprecedented damage along the Gulf Coast, resulting in billions of dollars in reconstruction costs. Indirect costs, including business interruption, supply chain disruptions, and lost productivity, further amplify the economic fallout. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, while devastating in its immediate impact, also triggered widespread fires that exacerbated the economic losses. These cascading effects underscore the interconnectedness of economic systems and the potential for widespread disruption following a major disaster.

Beyond immediate costs, long-term economic consequences can linger for years, even decades. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s, while not a singular event, represents a prolonged natural disaster with profound economic ramifications. Widespread crop failures and displacement of agricultural workers led to sustained economic hardship throughout the affected regions. Analyzing the long-term economic effects of such disasters highlights the importance of sustainable land management practices and the need for robust social safety nets to support affected communities. Furthermore, considering the economic impact allows for cost-benefit analyses of mitigation efforts. Investing in resilient infrastructure, early warning systems, and community preparedness measures can significantly reduce long-term economic losses, demonstrating the practical value of proactive disaster management strategies.

In conclusion, the economic impact of natural disasters presents a complex challenge, encompassing immediate costs, long-term disruptions, and cascading effects across various sectors. Understanding these intricate relationships informs policy decisions, resource allocation, and the development of sustainable strategies to mitigate future economic losses and foster resilient communities. By recognizing the economic dimension of these events, alongside human and environmental costs, a more comprehensive approach to disaster management can be achieved, leading to more effective preparedness and recovery efforts.

4. Geographic Scope

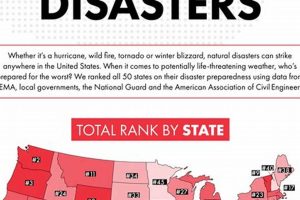

Geographic scope, representing the spatial extent of a natural disaster’s impact, constitutes a critical factor in determining its overall magnitude and historical significance. A disaster’s classification as among the “biggest” in US history often correlates with the breadth of its geographic reach, influencing the number of people affected, the scale of infrastructural damage, and the complexity of subsequent recovery efforts. Analyzing the geographic scope of past events reveals crucial insights into the interplay between natural forces and human vulnerability, informing preparedness strategies and mitigation efforts.

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 exemplifies the profound impact of extensive geographic scope. Spanning across multiple states, the flood inundated vast agricultural lands, displaced hundreds of thousands of people, and caused widespread economic devastation. The sheer scale of the affected area posed immense logistical challenges for relief and recovery operations, underscoring the need for coordinated multi-state and federal responses to large-scale disasters. Similarly, the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, while not a single event, impacted a vast swathe of the American Midwest, demonstrating the cumulative effects of prolonged environmental degradation over a wide geographic area. The resulting agricultural crisis and mass migration highlighted the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the far-reaching consequences of environmental instability.

Understanding the geographic scope of past disasters is essential for developing effective mitigation strategies. Mapping historical floodplains, identifying earthquake-prone regions, and delineating hurricane-vulnerable coastlines inform land-use planning, building codes, and evacuation procedures. Furthermore, recognizing the potential for geographically widespread impacts necessitates robust communication networks and coordinated emergency response systems across multiple jurisdictions. Analyzing geographic scope also reveals patterns of vulnerability, highlighting disparities in impact based on factors like socioeconomic status and access to resources. Addressing these disparities requires targeted interventions and equitable distribution of resources to ensure that vulnerable communities are adequately prepared and supported in the event of a disaster.

5. Long-Term Consequences

Long-term consequences represent a crucial dimension when assessing the true impact of natural disasters, particularly those considered among the “biggest” in US history. These consequences extend far beyond immediate damage, encompassing profound and lasting effects on social, economic, environmental, and psychological well-being. Understanding the multifaceted nature of long-term consequences is essential for developing comprehensive recovery strategies and mitigating the risks of future events.

One key aspect of long-term consequences is the disruption to community infrastructure and essential services. Events like Hurricane Katrina demonstrated the devastating impact on housing, transportation networks, healthcare facilities, and communication systems. The prolonged disruption of these essential services can hinder recovery efforts, displace populations, and exacerbate existing inequalities. Moreover, the economic fallout of major disasters can persist for years, affecting businesses, employment rates, and overall economic productivity. The Dust Bowl era exemplifies the long-term economic hardship resulting from environmental degradation and agricultural collapse. Beyond physical and economic impacts, natural disasters can leave lasting psychological scars on affected communities. Post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression are common among disaster survivors, highlighting the need for mental health support services as part of long-term recovery plans.

Furthermore, major natural disasters can trigger significant environmental changes with lasting consequences. Events like the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens dramatically altered the surrounding landscape, impacting ecosystems, water resources, and air quality for years to come. Understanding the long-term environmental effects of such events informs land management practices, conservation efforts, and policies aimed at mitigating future environmental risks. The practical significance of understanding long-term consequences lies in its ability to inform more effective disaster preparedness and recovery strategies. By recognizing the potential for long-term disruption, communities can develop comprehensive plans that address not only immediate needs but also the ongoing challenges of rebuilding infrastructure, revitalizing economies, supporting psychological well-being, and restoring environmental health. This long-term perspective is crucial for building more resilient communities capable of withstanding and recovering from the inevitable impacts of future natural disasters.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding significant natural disasters in the United States, providing concise and informative responses.

Question 1: Which single event is definitively considered the “biggest” natural disaster in US history?

Defining the single “biggest” disaster is complex due to the various metrics involved (e.g., mortality, economic impact, geographic scope). While events like the 1900 Galveston Hurricane caused immense loss of life, others like Hurricane Katrina had broader economic and social consequences. Therefore, no single event universally holds the title of “biggest.”

Question 2: How do mortality rates compare between historical and more recent disasters?

While historical events like the Galveston Hurricane and the Johnstown Flood resulted in significantly higher death tolls, advancements in forecasting, communication, and building codes have contributed to lower mortality in more recent events. However, recent disasters can still reveal vulnerabilities in preparedness and response systems, particularly concerning socially vulnerable populations.

Question 3: What role does geographic scope play in assessing the impact of a disaster?

Geographic scope significantly influences impact assessment. Events affecting larger areas, such as the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, present greater logistical challenges for relief efforts and often result in more widespread economic and social disruption. Wider impact necessitates coordinated responses across multiple jurisdictions and agencies.

Question 4: Beyond immediate damage, what are the long-term consequences often associated with major disasters?

Long-term consequences encompass various aspects, including prolonged economic hardship, disruption of essential services, lasting psychological impacts on affected populations, and significant environmental changes. These long-term effects necessitate comprehensive recovery plans addressing not just immediate needs but also sustained community rebuilding and support.

Question 5: How can historical disaster analysis inform present-day mitigation strategies?

Studying past disasters provides invaluable insights into vulnerabilities, infrastructure resilience, and the effectiveness of response strategies. This knowledge informs the development of building codes, evacuation plans, resource allocation strategies, and public awareness campaigns, contributing to enhanced community preparedness and more effective mitigation efforts.

Question 6: What is the significance of considering economic impact when evaluating natural disasters?

Economic impact represents a crucial factor in understanding the full consequences of disasters. Direct costs like property damage and indirect costs like business interruption contribute to the overall economic burden. Analyzing economic impact enables cost-benefit analyses of mitigation measures, informing resource allocation for disaster preparedness and recovery.

Understanding the diverse facets of natural disasters, from mortality and economic impact to geographic scope and long-term consequences, provides a more comprehensive understanding of their significance. This knowledge serves as a critical foundation for enhancing preparedness, mitigating future risks, and fostering more resilient communities.

For further exploration, the following sections delve into specific case studies of significant natural disasters in US history, offering detailed analyses of their causes, consequences, and the lessons learned.

Biggest Natural Disasters in US History

Exploring the concept of the “biggest” natural disaster in US history requires a nuanced understanding of various factors. This exploration has highlighted the significance of considering not only mortality figures but also economic impact, geographic scope, and long-term consequences. While pinpointing a single, definitively “biggest” event remains challenging due to the diverse nature of these factors, the analysis of prominent disastersfrom the 1900 Galveston Hurricane to Hurricane Katrinareveals critical insights into the complex interplay of natural forces and human vulnerability. Examining these events underscores the importance of preparedness, mitigation strategies, and community resilience in minimizing the devastating effects of future disasters.

Ultimately, understanding the historical context of past disasters provides invaluable lessons for shaping future approaches to disaster management. Continued research, improved infrastructure, enhanced warning systems, and a commitment to community-level preparedness represent crucial steps towards mitigating the impacts of inevitable future events. By acknowledging the multifaceted nature of disaster impact and prioritizing proactive mitigation strategies, societies can strive towards a future better equipped to withstand and recover from the profound challenges posed by natural hazards.