Catastrophic events arising from natural forces, such as earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and pandemics, have shaped human history, often resulting in immense loss of life and widespread devastation. Determining the single most destructive event requires careful consideration of various factors, including direct mortality, long-term consequences, and the availability of reliable historical records. For instance, the 1918 influenza pandemic, while not a geological event, resulted in a staggering death toll across the globe.

Understanding the scale and impact of these extreme events provides crucial context for developing effective disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies. Analyzing historical data allows for the identification of vulnerable populations and regions, informing resource allocation and infrastructure development. Furthermore, examining past catastrophes contributes to a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between human societies and the natural world, highlighting the importance of sustainable practices and resilience building.

This exploration will delve into several contenders for the title of most devastating natural disaster, examining specific examples and their impact on affected populations. Factors considered will include immediate casualties, subsequent societal disruption, and long-term effects on public health, economic stability, and the environment.

Preparedness and Mitigation Strategies

Learning from the past is crucial for mitigating future risks. Examining the impact of history’s most destructive natural events provides valuable insights into effective preparedness measures. The following recommendations draw upon lessons learned from such catastrophes:

Tip 1: Develop robust early warning systems. Accurate and timely warnings are essential for enabling effective evacuations and minimizing casualties. Investment in advanced monitoring technologies and communication infrastructure is vital.

Tip 2: Implement stringent building codes. Structures designed to withstand extreme forces significantly reduce the risk of collapse and protect occupants during earthquakes, hurricanes, and other events.

Tip 3: Establish comprehensive evacuation plans. Clearly defined evacuation routes and procedures, coupled with public education and drills, facilitate swift and orderly movement of populations away from danger zones.

Tip 4: Secure essential resources. Stockpiling food, water, medical supplies, and other critical resources ensures communities can sustain themselves in the immediate aftermath of a disaster.

Tip 5: Invest in community education and training. Public awareness campaigns focused on disaster preparedness empower individuals to take appropriate actions to protect themselves and their families.

Tip 6: Foster international collaboration. Sharing knowledge, resources, and best practices across borders strengthens global capacity for disaster response and recovery.

Tip 7: Protect vulnerable ecosystems. Healthy ecosystems, such as coastal wetlands and forests, provide natural buffers against the impact of natural hazards.

Adopting these measures can significantly reduce vulnerability to catastrophic natural events. Proactive planning and investment in disaster preparedness ultimately save lives and minimize the devastating impacts on communities and infrastructure.

By integrating these lessons into disaster management strategies, societies can better prepare for and mitigate the risks posed by the inevitable occurrence of future catastrophic events.

1. Magnitude

Magnitude, a measure of the energy released during a natural event, plays a critical role in determining its potential for devastation. While not solely responsible for the overall deadliness, a higher magnitude often correlates with increased impact, influencing factors such as geographic reach and intensity of destruction. Understanding magnitude is therefore crucial for assessing the potential consequences of these events and for developing effective mitigation strategies.

- Earthquake Magnitude:

Earthquake magnitude, typically measured using the Richter scale, quantifies the energy released at the earthquake’s source. Higher magnitudes correspond to stronger ground shaking and a greater potential for widespread damage. The 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile, estimated at magnitude 9.5, holds the record as the most powerful earthquake ever recorded, resulting in significant casualties and widespread destruction across a vast area.

- Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI):

The VEI measures the explosiveness of volcanic eruptions based on factors like eruption plume height, volume of ejected material, and duration. Larger VEI values indicate more powerful and potentially devastating eruptions. The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, with a VEI of 7, caused widespread atmospheric changes leading to the “Year Without a Summer” and resulting in global crop failures and famine.

- Tropical Cyclone Intensity:

Tropical cyclones are categorized based on wind speed, using scales like the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Higher categories signify stronger winds, heavier rainfall, and increased potential for storm surge, all of which contribute to potential devastation. The 1970 Bhola cyclone, one of the deadliest tropical cyclones in recorded history, devastated the Ganges Delta region with intense winds and storm surge, resulting in a massive loss of life.

- Pandemic Severity:

While not measured on a single standardized scale, pandemic severity considers factors such as mortality rate, transmissibility, and geographic spread. The 1918 influenza pandemic, with its exceptionally high mortality rate and rapid global spread, stands as a stark example of a high-magnitude pandemic with devastating consequences.

Analyzing magnitude in conjunction with other factors like population density, vulnerability, and preparedness provides a more comprehensive understanding of the potential impact of natural disasters. By recognizing the role of magnitude, societies can develop more effective risk assessments and implement targeted strategies to minimize casualties and damage from future catastrophic events.

2. Mortality

Mortality, representing the direct loss of human life, serves as a stark and quantifiable measure of a natural disaster’s impact. While not the sole indicator of a disaster’s overall devastation, mortality figures often dominate public perception and historical narratives. Analyzing mortality data, alongside other factors such as long-term health consequences and societal disruption, provides crucial insights for understanding the true scope of these catastrophic events.

- Direct Casualties:

Direct casualties encompass immediate deaths resulting from the initial impact of the disaster. This includes fatalities from building collapses during earthquakes, drowning during tsunamis, or burns from volcanic eruptions. The immediate death toll significantly influences the classification of “deadliest” disasters. For example, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami resulted in an estimated 230,000 direct casualties across multiple countries.

- Indirect Casualties:

Indirect casualties result from the aftermath of the disaster, including deaths from injuries, disease outbreaks, famine, and exposure. These secondary impacts can significantly contribute to the overall mortality burden, often exceeding the initial death toll. The 1918 influenza pandemic provides a clear example, where the virus itself caused many direct deaths, while subsequent secondary infections and complications significantly increased the overall mortality.

- Demographic Impact:

Mortality figures can reveal significant demographic shifts within affected populations. Disasters may disproportionately impact specific age groups or demographic segments. For instance, the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and subsequent tsunami significantly altered the city’s population structure, affecting age demographics, particularly the youngest members of the society, along with its economic balance and societal structures.

- Challenges in Data Collection:

Accurately determining mortality figures in the aftermath of large-scale disasters presents significant challenges. Factors such as the destruction of infrastructure, displacement of populations, and the sheer scale of the event can hinder data collection efforts. Historical records may also be incomplete or unreliable, particularly for events occurring in the distant past. This uncertainty underscores the need for cautious interpretation of mortality data and recognition of potential underestimations in historical accounts.

Examining mortality from these various perspectives offers a deeper understanding of the human cost of natural disasters. By analyzing mortality data in conjunction with other key factors like magnitude, geographic impact, and long-term consequences, a more comprehensive picture of these catastrophic events emerges, enabling more informed disaster preparedness and response strategies. This broader approach allows for more effective mitigation efforts and a better understanding of the complex interplay between natural forces and human vulnerability.

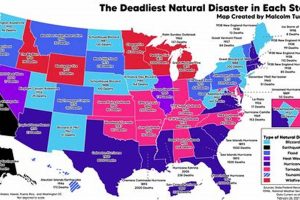

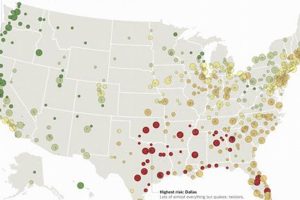

3. Geographic Impact

Geographic impact, encompassing the spatial extent and characteristics of the affected area, plays a crucial role in determining the overall devastation of a natural disaster. The interaction between the disaster’s nature and the region’s specific geographic features significantly influences the scale of destruction and resulting casualties. Understanding this interplay is essential for effective disaster preparedness and mitigation.

Cause and Effect: Geographic features can exacerbate the impact of natural disasters. Coastal regions, for instance, are particularly vulnerable to tsunamis and storm surges. Mountainous terrain can amplify the effects of earthquakes, leading to landslides and avalanches. Densely populated areas experience higher casualties due to the concentration of people within a limited space. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, followed by a tsunami and fires, demonstrated the devastating impact of a geographically focused disaster on a densely populated urban center. Similarly, the 2010 Haiti earthquakes catastrophic impact was amplified by the countrys dense population, precarious infrastructure, and location on active fault lines.

Importance as a Component: Geographic impact significantly contributes to classifying a disaster as “deadliest.” Widespread destruction across a large geographic area, impacting multiple communities or even entire countries, results in higher casualty numbers and widespread societal disruption. The 1918 influenza pandemic, while not geographically limited like a localized earthquake or volcanic eruption, exhibited widespread geographic reach, impacting populations across the globe. Its rapid spread, facilitated by global travel and trade routes, contributed significantly to its devastating mortality rate.

Practical Significance: Understanding the role of geographic impact in shaping disaster outcomes informs disaster preparedness and response strategies. Identifying high-risk areas based on geographic vulnerabilities allows for targeted resource allocation, development of early warning systems, and implementation of appropriate building codes. Recognizing the specific geographic characteristics of a region, including its proximity to fault lines, coastlines, or volcanic zones, enables the development of tailored mitigation strategies that reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience. Mapping vulnerable populations and critical infrastructure within a specific geographic context further refines these strategies.

The interplay between a disaster’s nature and the geographic characteristics of the affected region ultimately shapes the event’s severity. Analyzing historical data, combined with ongoing monitoring and assessment of geographic vulnerabilities, equips communities and nations with the necessary tools to anticipate, mitigate, and respond effectively to the inevitable occurrence of future disasters. Integrating this geographic perspective into disaster management frameworks fosters resilience, reduces human suffering, and minimizes the devastating consequences of natural hazards.

4. Long-term Consequences

The true impact of a catastrophic natural disaster extends far beyond the immediate aftermath. Long-term consequences, often unfolding over years or even decades, shape the affected region’s trajectory, influencing its social fabric, economic stability, and environmental landscape. Understanding these long-term effects is crucial for classifying a disaster as truly “deadliest” and for developing effective recovery and resilience-building strategies.

- Economic Disruption:

Catastrophic events cause profound economic disruption, impacting infrastructure, industries, and livelihoods. Damage to transportation networks, factories, and agricultural lands leads to production losses, job displacement, and market instability. The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, for example, caused extensive damage to nuclear power plants, leading to long-term energy shortages and impacting industrial output. The long-term economic consequences of such disasters can hinder a region’s development for years, even decades, requiring substantial investment and strategic planning for recovery.

- Social and Psychological Impacts:

Beyond the immediate loss of life, natural disasters inflict deep social and psychological wounds on affected communities. Displacement, loss of loved ones, and the disruption of social networks contribute to widespread trauma, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. The 1995 Kobe earthquake, which resulted in significant loss of life and widespread destruction, had profound psychological impacts on survivors, highlighting the importance of mental health support in disaster recovery efforts. These social and psychological scars can persist for generations, impacting community cohesion and well-being.

- Environmental Degradation:

Natural disasters often trigger significant environmental damage, altering landscapes, disrupting ecosystems, and increasing vulnerability to future hazards. Tsunamis can contaminate freshwater sources with saltwater, rendering them unusable for agriculture and drinking. Volcanic eruptions release massive amounts of ash and gases into the atmosphere, impacting air quality and potentially triggering climate change. The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, which caused widespread tsunamis and atmospheric changes, provides a stark example of the long-term environmental consequences of a major volcanic event. Addressing these environmental impacts requires sustained efforts in restoration and adaptation.

- Public Health Challenges:

The aftermath of a natural disaster often presents significant public health challenges. Damage to healthcare infrastructure, disruption of sanitation systems, and displacement of populations can lead to increased risk of infectious disease outbreaks, malnutrition, and chronic health problems. The 2010 Haiti earthquake, which devastated the country’s already fragile healthcare system, resulted in a surge of cholera cases, highlighting the vulnerability of disaster-stricken populations to public health crises. Strengthening public health infrastructure and implementing robust disease surveillance systems are critical for mitigating these long-term health risks.

Considering these long-term consequences provides a more complete understanding of the devastating impact of natural disasters. The “deadliest” disasters are not solely defined by immediate casualties, but also by the enduring challenges they pose to affected communities. By recognizing the complex interplay of economic, social, environmental, and public health factors in the long-term aftermath of these events, societies can develop more effective strategies for resilience-building, ensuring a more sustainable and equitable recovery process. This comprehensive approach acknowledges the true scope of these catastrophic events and emphasizes the importance of long-term planning and investment in disaster preparedness and mitigation.

5. Historical Context

Understanding historical context is crucial for accurately assessing the impact of natural disasters. Historical records provide valuable data on past events, enabling comparisons across different time periods and offering insights into long-term trends and patterns. However, the availability and reliability of historical data vary significantly, influencing the ability to definitively identify the single “deadliest” natural disaster in history. This exploration delves into the multifaceted role of historical context in understanding these catastrophic events.

- Data Availability and Reliability:

The further back in time, the more fragmented and potentially less reliable historical records become. Early civilizations often lacked systematic methods for recording casualties and damage from natural disasters. For events occurring centuries ago, estimates rely on interpretations of archaeological evidence, historical chronicles, and anecdotal accounts, which may be incomplete or subject to biases. This inherent limitation makes direct comparisons between ancient and modern disasters challenging, as modern events benefit from more sophisticated data collection and analysis techniques.

- Societal Vulnerability and Resilience:

Historical context illuminates how societal structures, technologies, and cultural practices influence vulnerability and resilience to natural disasters. Societies with limited infrastructure, rudimentary healthcare systems, and inadequate disaster preparedness measures experience greater impacts from natural hazards. The 1883 Krakatoa eruption, for instance, had a devastating impact on surrounding communities due to the limited communication and transportation technologies available at the time. Modern societies, while still vulnerable, often possess more advanced infrastructure and disaster management protocols, potentially mitigating the overall impact of similar events.

- Evolving Understanding of Natural Hazards:

Scientific understanding of natural hazards has evolved significantly over time. Historical accounts often attribute disasters to supernatural forces or divine retribution, lacking the scientific framework to explain the underlying geological or meteorological processes. This evolving understanding influences how societies perceive, prepare for, and respond to natural disasters. The shift from superstitious explanations to scientific understanding has enabled the development of more effective prediction, mitigation, and response strategies.

- Shifting Baselines and Changing Perspectives:

As societies experience more frequent and intense natural disasters, the baseline for what constitutes a “catastrophic” event shifts. Events that might have been considered unprecedented in the past may become more commonplace in the future due to factors such as climate change and population growth. Historical context provides a crucial reference point for understanding these shifting baselines and appreciating the relative magnitude of past events in comparison to contemporary challenges. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of disaster trends and informs adaptation strategies for future scenarios.

Considering historical context provides crucial insights into the complex interplay of natural forces and human societies. While accurately ranking historical disasters in terms of “deadliest” remains challenging due to limitations in data availability and evolving societal vulnerabilities, understanding the historical context of these events illuminates crucial lessons for building more resilient communities and mitigating the impacts of future disasters. Analyzing historical trends alongside modern data strengthens disaster preparedness strategies and fosters a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term consequences of these catastrophic events.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the deadliest natural disasters in history, providing concise and informative responses based on available data and historical records.

Question 1: What is considered the deadliest natural disaster in recorded history?

Pinpointing the single deadliest disaster is complex due to variations in record-keeping throughout history. However, the 1931 China floods, with estimated fatalities ranging from millions to four million, are often cited as the most devastating in terms of human life lost.

Question 2: How do pandemics compare to geological events in terms of mortality?

Pandemics, while not geological, can cause widespread mortality comparable to or exceeding major geological events. The 1918 influenza pandemic, for example, resulted in an estimated 50 to 100 million deaths globally, rivaling or exceeding many large-scale earthquakes and tsunamis in terms of total fatalities.

Question 3: Does higher magnitude always equate to higher mortality in natural disasters?

Not necessarily. While magnitude often correlates with increased destructive potential, factors such as population density, building codes, and disaster preparedness significantly influence the final death toll. A lower-magnitude event in a densely populated area with inadequate infrastructure can result in higher casualties than a higher-magnitude event in a sparsely populated region with robust building codes.

Question 4: How has improved technology impacted mortality rates from natural disasters?

Advancements in early warning systems, building materials, and disaster response protocols have contributed to a decrease in mortality rates from natural disasters in many regions. However, increasing global population density and the potential impacts of climate change present ongoing challenges.

Question 5: What are the long-term impacts that contribute to a disaster’s overall deadliness beyond immediate casualties?

Long-term impacts such as famine, disease outbreaks, economic devastation, and psychological trauma contribute significantly to the overall burden of a disaster. These factors, often unfolding over years or even decades, affect long-term mortality and societal well-being, extending the disaster’s reach beyond the initial event.

Question 6: How does understanding historical context improve current disaster preparedness strategies?

Studying past disasters provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of various mitigation and response strategies. Analyzing historical data reveals vulnerabilities, informs infrastructure development, and shapes public policy, contributing to more effective disaster preparedness and ultimately reducing future losses.

Understanding the complex factors contributing to the deadliness of natural disasters is crucial for developing effective mitigation and response strategies. Continued research, improved data collection, and international collaboration are essential for minimizing the devastating impacts of future catastrophic events.

Exploring specific historical disasters provides further context and insights into the devastating impacts of these events. The following sections will delve into case studies of some of the most impactful natural disasters in recorded history.

Conclusion

Catastrophic natural events, capable of inflicting immense devastation and claiming countless lives, represent a profound challenge to human societies. This exploration has examined the multifaceted nature of these events, considering factors such as magnitude, mortality, geographic impact, long-term consequences, and historical context to provide a comprehensive perspective on the deadliest natural disasters in history. While definitively ranking these events presents inherent challenges due to limitations in historical data and evolving societal vulnerabilities, the analysis underscores the crucial importance of understanding the complex interplay of natural forces and human societies.

The quest to understand the deadliest natural disasters is not merely an academic exercise; it serves as a critical foundation for building more resilient communities and mitigating the impacts of future catastrophic events. Continued research, improved data collection, and a commitment to global collaboration are essential for advancing disaster preparedness strategies and reducing human suffering. By integrating historical lessons with scientific advancements and proactive planning, societies can strive to minimize the devastating consequences of these inevitable natural hazards and safeguard future generations.