Deities associated with destruction, chaos, or natural calamities feature prominently in numerous mythologies worldwide. These figures often embody the unpredictable and awe-inspiring power of nature, serving as explanations for earthquakes, floods, volcanic eruptions, and other catastrophic events. For instance, the Japanese deity Namazu is believed to cause earthquakes when its guardians lower their guard.

Exploring these figures provides valuable insights into how ancient cultures perceived and coped with the destructive forces of nature. These narratives frequently emphasize the importance of respect for the natural world and the potential consequences of human actions. Studying such figures offers a lens through which to examine cultural anxieties, societal structures, and the human relationship with the environment. Furthermore, their enduring presence in literature and art underscores the enduring power of these archetypal figures.

This understanding provides a foundation for further exploration of specific deities, comparative mythology, and the broader role of mythology in shaping human understanding of the world. From examining individual pantheons to analyzing the psychological and sociological implications of disaster myths, the avenues for deeper investigation are numerous.

Disaster Preparedness Tips

Preparation for catastrophic events, whether natural or human-caused, is crucial for minimizing potential harm and ensuring a swift recovery. The following recommendations offer practical guidance for enhancing resilience in the face of unforeseen circumstances.

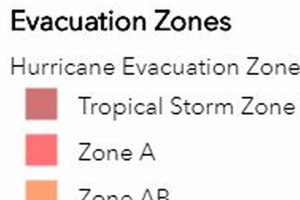

Tip 1: Develop an Emergency Plan: A comprehensive plan should outline evacuation routes, communication protocols, designated meeting points, and responsibilities for each household member. Regularly review and practice the plan to ensure its effectiveness.

Tip 2: Assemble an Emergency Kit: This kit should contain essential supplies for survival, including water, non-perishable food, first-aid supplies, medications, a flashlight, a radio, and extra batteries. Periodically check and replenish these supplies.

Tip 3: Secure Important Documents: Store vital documents, such as birth certificates, passports, insurance policies, and medical records, in a waterproof and fireproof container, or consider digital backups stored securely in the cloud.

Tip 4: Learn Basic First Aid and CPR: Possessing these skills can prove invaluable in emergencies, providing immediate assistance to injured individuals before professional help arrives.

Tip 5: Stay Informed: Monitor weather reports and official alerts through reliable sources. Understanding potential threats enables timely responses and informed decision-making.

Tip 6: Strengthen Your Home: Implementing preventive measures, such as reinforcing roofs, securing windows, and clearing gutters, can mitigate damage from severe weather events.

Tip 7: Establish Community Connections: Building strong relationships with neighbors can foster mutual support during and after a disaster, facilitating collaborative recovery efforts.

Proactive planning and preparation significantly enhance resilience in the face of unforeseen challenges. By adopting these measures, individuals and communities can minimize risks, protect lives, and navigate difficult situations with greater confidence.

Through careful consideration of these strategies and consistent implementation, individuals and communities can create a safer and more secure environment for themselves and future generations.

1. Divine Embodiment of Destruction

The concept of a “god of disaster” often involves the personification of destructive forces as a deity. This “divine embodiment of destruction” provides a framework for understanding calamities within a cultural and religious context. Examining its various facets reveals deeper insights into the human relationship with disaster.

- Force of Nature Personified:

Gods of disaster represent the raw, untamed power of nature. They embody earthquakes, floods, storms, volcanic eruptions, and other events that reshape landscapes and disrupt human life. Examples include Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea and earthquakes, and Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes. This personification allows cultures to conceptualize and interact with these otherwise abstract and terrifying forces.

- Divine Agency and Causality:

Attributing disasters to a divine entity provides an explanation for seemingly random events. Rather than viewing calamities as purely natural phenomena, they become acts of a divine will, whether for punishment, testing, or simply a demonstration of power. This perspective can offer a sense of order and meaning in the face of chaos.

- Ambivalence of Power:

Gods of disaster often embody both creation and destruction. While they bring devastation, they can also be associated with renewal and regeneration. Volcanic eruptions, for instance, destroy existing life but also create fertile land. This duality reflects the cyclical nature of nature and the understanding that destruction can pave the way for new beginnings.

- Focus of Ritual and Appeasement:

The fear and reverence inspired by these deities often lead to rituals and practices aimed at appeasing them and mitigating their destructive potential. Offerings, prayers, and specific behaviors become ways to maintain a harmonious relationship with the divine and avert potential disasters. This highlights the active role humans believe they can play in influencing the divine will.

Understanding these facets of “divine embodiment of destruction” offers a nuanced perspective on the complex role of “gods of disaster” in various cultures. They serve not only as explanations for natural events but also as focal points for cultural values, anxieties, and attempts to navigate a world often shaped by unpredictable forces.

2. Explanation for Calamities

The concept of a “god of disaster” frequently serves as an explanatory model for calamities, offering a framework for understanding otherwise inexplicable events. This connection between deity and disaster provides insights into how cultures interpret and respond to the unpredictable forces of nature.

- Attribution of Agency:

Assigning agency to a deity provides a narrative for seemingly random events. Disasters become less about arbitrary natural occurrences and more about the actions of a divine being, whether motivated by anger, punishment, or testing. This attribution can offer a sense of order and control in the face of chaos.

- Narrative and Meaning-Making:

Myths surrounding disaster deities provide narratives that explain the origins and nature of catastrophic events. These stories offer cultural explanations, often imbued with moral lessons or warnings. The story of Noah’s Ark, for example, attributes the flood to divine judgment on human wickedness.

- Cultural Interpretation of Natural Phenomena:

Different cultures interpret natural events through the lens of their specific beliefs. In some traditions, earthquakes might be attributed to a subterranean deity shifting its position, while in others, volcanic eruptions might be seen as the breath of an angry fire god. These interpretations reflect cultural values and perspectives on the natural world.

- Psychological Coping Mechanism:

Attributing disasters to divine agency can provide a psychological coping mechanism. By assigning a cause, even a supernatural one, individuals and communities can begin to process the trauma and grief associated with catastrophic events. This framework allows for the development of rituals and practices aimed at appeasing the deity and mitigating future disasters.

By exploring the connection between “god of disaster” and “explanation for calamities,” we gain a deeper understanding of the human need to make sense of the unpredictable and often destructive forces that shape our world. These narratives, while diverse in their specific expressions, reveal a common human impulse to find meaning and order amidst chaos.

3. Object of Reverence and Fear

The duality of reverence and fear forms a core element in the human relationship with deities associated with disaster. These powerful figures, capable of unleashing destruction and chaos, evoke both awe and terror, shaping religious practices and cultural narratives. This complex interplay influences how societies interact with the natural world and cope with the unpredictable nature of catastrophic events.

Reverence stems from the recognition of the deity’s immense power. Just as a king or ruler commands respect, so too does the god of disaster hold sway over forces that can reshape landscapes and alter human destinies. This respect often manifests in rituals, offerings, and prayers intended to appease the deity and secure its favor. Conversely, fear arises from the potential for destruction. The same power that inspires awe can also unleash devastation, leading to a sense of vulnerability and dread. This fear motivates propitiatory actions, driving individuals and communities to seek protection from the deity’s wrath. The worship of Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea and earthquakes, exemplifies this duality. Sailors offered sacrifices to ensure safe passage across the waves, while coastal communities sought to appease him to avert devastating earthquakes. Similarly, the Hawaiian goddess Pele, associated with volcanoes, inspired both reverence for her creative power and fear of her destructive potential, shaping cultural practices and land management traditions around volcanic activity.

Understanding this interplay of reverence and fear provides crucial insight into the cultural significance of disaster deities. These figures are not simply personifications of natural forces; they represent complex psychological and social responses to the unpredictable and often destructive aspects of the world. Recognizing this duality illuminates how cultures grapple with vulnerability, seek to mitigate risks, and find meaning in the face of overwhelming events. This understanding can inform disaster preparedness strategies, cultural sensitivity, and historical analysis, highlighting the enduring relevance of these powerful figures in shaping human societies.

4. Reflection of Societal Anxieties

Deities associated with disaster often serve as mirrors to societal anxieties, reflecting cultural fears and preoccupations surrounding unpredictable and destructive forces. Examining these figures provides valuable insight into the specific concerns of different societies and their attempts to cope with potential threats. This exploration reveals the complex relationship between cultural beliefs and the human experience of vulnerability.

- Fear of the Unknown:

Disaster deities embody the unpredictable nature of catastrophic events. They represent the unknown, the forces beyond human control that can disrupt lives and reshape landscapes. This reflects a fundamental human anxiety about the precariousness of existence and the constant potential for unforeseen disruption. The Japanese fear of earthquakes, reflected in the reverence for Namazu, exemplifies this connection.

- Moral and Social Order:

In many cultures, disaster deities are linked to concepts of divine justice or punishment. Disasters are interpreted as consequences of human actions, reflecting societal anxieties about moral and social order. The story of Noah’s Ark, where a flood is sent as divine punishment, demonstrates this connection. This association reinforces cultural norms and emphasizes the importance of adhering to societal values.

- Environmental Concerns:

Disaster deities often embody specific environmental threats, such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, or floods. These figures reflect societal anxieties about the power of nature and the potential for environmental instability. The reverence for Pele, the Hawaiian volcano goddess, underscores the awareness and respect for volcanic activity in Hawaiian culture. This reflects an attempt to understand and coexist with a powerful natural force.

- Existential Vulnerability:

The destructive power of disaster deities highlights human vulnerability in the face of overwhelming forces. This reflects a deeper existential anxiety about the fragility of life and the constant presence of potential loss. The worship of deities associated with death and the underworld, often intertwined with disaster deities, demonstrates this awareness of mortality. This recognition of vulnerability shapes cultural practices and belief systems surrounding death and the afterlife.

By analyzing disaster deities as reflections of societal anxieties, we gain a deeper understanding of the cultural values, fears, and coping mechanisms of different societies. These figures offer a window into how communities grapple with the unpredictable nature of the world and attempt to find meaning and order in the face of potential catastrophe. This understanding transcends specific pantheons and reveals universal human concerns about vulnerability, mortality, and the search for security in a world often shaped by forces beyond our control.

5. Source of Mythological Narratives

Deities associated with disaster frequently serve as central figures in mythological narratives, providing a framework for understanding the origins of calamities and the complex relationship between humanity and the natural world. Exploring these narratives offers valuable insights into cultural values, anxieties, and attempts to make sense of unpredictable and often destructive forces.

- Explaining Catastrophic Events:

Myths featuring disaster deities offer explanations for the occurrence of earthquakes, floods, volcanic eruptions, and other catastrophic events. These narratives often attribute such events to the deity’s actions, whether intentional or accidental. For example, in Japanese mythology, the giant catfish Namazu thrashing about causes earthquakes. These stories provide a causal link between the supernatural and the natural, offering a framework for understanding otherwise inexplicable phenomena.

- Teaching Moral Lessons:

Disaster narratives often convey moral lessons or warnings. They may depict calamities as divine punishment for human transgressions, emphasizing the importance of adhering to societal values and respecting the natural world. The story of Noah’s Ark, for instance, presents the flood as divine retribution for human wickedness. These narratives serve as cautionary tales, reinforcing cultural norms and promoting specific behaviors.

- Exploring Human-Nature Relationships:

Myths surrounding disaster deities explore the complex relationship between humanity and the natural world. They depict both the power of nature and human vulnerability in the face of its destructive forces. The Hawaiian goddess Pele, associated with volcanoes, embodies both the creative and destructive potential of nature, highlighting the need for respect and understanding. These narratives provide a framework for negotiating this relationship and finding a place within the natural order.

- Providing Cultural Context:

Disaster narratives are deeply embedded within specific cultural contexts, reflecting the unique values, beliefs, and experiences of different societies. These stories offer insights into how cultures perceive and respond to natural disasters, shaping their rituals, practices, and understanding of the world. The prevalence of flood myths in cultures located near major rivers or coastlines, for example, reflects the lived experiences and anxieties of these communities. Analyzing these narratives provides a lens through which to understand cultural perspectives on risk, resilience, and the relationship between humanity and the environment.

By examining the role of disaster deities as sources of mythological narratives, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complex interplay between cultural beliefs, natural phenomena, and the human search for meaning in the face of unpredictable and often destructive forces. These stories offer valuable insights into how societies have historically grappled with disaster, providing a foundation for understanding contemporary perspectives and approaches to disaster preparedness and resilience.

6. Symbol of Unpredictable Forces

Gods of disaster often function as potent symbols of unpredictable forces, embodying the chaotic and uncontrollable aspects of nature. Examining this symbolic representation provides insights into how cultures conceptualize and respond to the inherent uncertainties of the world around them. This exploration reveals deep-seated anxieties and coping mechanisms related to the precariousness of human existence.

- Embodiment of Chaos:

Disaster deities personify the inherent chaos present in the natural world. They represent the untamed forces that defy human control and can disrupt established order. This symbolism reflects the anxieties associated with unpredictable events, such as earthquakes, storms, and volcanic eruptions, which can have devastating consequences. The Greek god Typhon, a monstrous figure associated with volcanic eruptions and storms, embodies this chaotic power.

- The Unknowable and Uncontrollable:

These deities often represent the unknowable and uncontrollable aspects of existence. Their actions can be arbitrary and unpredictable, mirroring the seemingly random nature of disasters. This symbolism highlights the limitations of human knowledge and the inherent uncertainty of life. The Japanese deity Namazu, whose movements cause earthquakes, exemplifies this unpredictable nature.

- Catalyst for Change and Transformation:

While often associated with destruction, disaster deities can also symbolize change and transformation. Catastrophic events, though devastating, can also lead to renewal and the creation of new landscapes, both physical and metaphorical. This duality reflects the cyclical nature of existence, where destruction often precedes creation. The Hindu goddess Kali, associated with destruction and creation, embodies this transformative power.

- Reminder of Human Vulnerability:

The unpredictable nature of disaster deities serves as a constant reminder of human vulnerability. They underscore the precariousness of life and the ever-present potential for loss and disruption. This symbolism encourages reflection on the limitations of human power and the importance of resilience in the face of adversity. The figure of Death, often associated with disaster and depicted as a powerful, indiscriminate force, embodies this vulnerability.

By understanding disaster deities as symbols of unpredictable forces, one gains a deeper appreciation for the complex ways in which cultures grapple with uncertainty and the precarious nature of existence. These figures represent not only the destructive potential of the natural world but also the transformative power of chaos and the enduring human need to find meaning and order amidst the unpredictable flow of events. This exploration highlights the psychological and cultural significance of these powerful symbols and their enduring relevance in shaping human understanding of the world.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding deities associated with disaster, aiming to provide clear and informative responses.

Question 1: Why do cultures create deities associated with destruction?

Attributing destructive natural forces to a divine entity offers a framework for understanding and coping with unpredictable and often traumatic events. These figures provide explanations for calamities, offer a focus for anxieties, and inspire rituals aimed at mitigating potential threats.

Question 2: Are these deities solely malevolent forces?

Not necessarily. While associated with destruction, many disaster deities also embody aspects of creation and renewal. Their power, while potentially destructive, can also be a catalyst for change and regeneration. This duality reflects the cyclical nature of many natural processes.

Question 3: How do these figures differ across cultures?

Specific attributes and narratives surrounding disaster deities vary considerably across cultures, reflecting unique environmental contexts, social structures, and belief systems. While some cultures emphasize the destructive aspects, others highlight the transformative or regenerative potential of these figures.

Question 4: Do these beliefs influence practical responses to disasters?

Cultural beliefs surrounding disaster deities can significantly influence practical responses to such events. Rituals, offerings, and specific behaviors may be employed to appease the deity and mitigate potential future disasters. These practices often inform community-based disaster preparedness and response strategies.

Question 5: What can be learned from studying these deities?

Studying disaster deities offers valuable insights into cultural values, anxieties, and coping mechanisms related to unpredictable events. This exploration can inform contemporary disaster preparedness strategies, promote cultural understanding, and enhance historical analysis.

Question 6: Is the concept of a “god of disaster” still relevant today?

While specific religious beliefs may vary, the underlying human need to understand and cope with unpredictable forces remains relevant. Examining historical and cultural perspectives on disaster can inform current approaches to risk management, resilience building, and community support in the face of catastrophic events.

Understanding the cultural and historical context of disaster deities provides a foundation for navigating the complexities of human interaction with the natural world and its inherent uncertainties. This knowledge fosters a more nuanced perspective on disaster preparedness, cultural sensitivity, and the enduring human search for meaning in the face of challenging circumstances.

Further exploration of specific deities and their associated myths offers deeper insights into these complex figures and their enduring significance.

Conclusion

Exploration of the “god of disaster” archetype reveals a complex interplay between cultural beliefs, natural phenomena, and the human experience of vulnerability. These figures, prominent across diverse mythologies, serve not merely as explanations for catastrophic events but also as reflections of societal anxieties, sources of moral instruction, and symbols of unpredictable forces. From the wrathful Poseidon to the transformative Kali, these deities embody the enduring human struggle to comprehend and cope with the precarious nature of existence.

Further investigation into individual pantheons and specific disaster narratives offers a deeper understanding of the cultural nuances and psychological dimensions associated with these powerful figures. Continued study promises valuable insights into human resilience, the ongoing relationship between humanity and the natural world, and the enduring search for meaning in the face of unpredictable forces. This knowledge provides a crucial foundation for navigating contemporary challenges related to disaster preparedness, environmental awareness, and cross-cultural understanding in an increasingly interconnected world.