Quantifying the absolute most powerful event in nature’s destructive repertoire is complex. Power can be measured by magnitude, like the Richter scale for earthquakes, or by the overall impact, such as lives lost or economic damage. A high-magnitude earthquake in an unpopulated area might register higher on a seismograph than a lower-magnitude quake in a dense city, yet the latter could cause significantly more devastation. Furthermore, various types of events earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, hurricanes, wildfires possess distinct characteristics that make direct comparisons challenging. One might compare the energy released by a volcanic eruption to the kinetic energy of a hurricane, but translating that into a universally applicable scale of “strength” is difficult. Therefore, discussions of extreme geophysical events often focus on specific categories or specific impacts, like the deadliest tsunami or the costliest hurricane.

Understanding the upper limits of nature’s destructive potential is crucial for preparedness and mitigation efforts. Analyzing historical data, coupled with advanced modeling techniques, allows scientists to refine predictions and develop more effective early warning systems. This knowledge informs building codes, evacuation plans, and resource allocation for disaster relief. Examining past catastrophic events also reveals societal vulnerabilities, prompting improvements in infrastructure and emergency response protocols. Ultimately, comprehending the mechanisms and potential consequences of extreme natural events is essential for minimizing their impact on human populations and infrastructure.

This article will explore several categories of high-impact natural events, examining their underlying causes, destructive capabilities, and notable historical examples. It will also discuss ongoing research and innovations aimed at improving prediction, mitigation, and response strategies to protect communities worldwide.

Preparing for High-Impact Natural Events

Preparedness is crucial for mitigating the impact of catastrophic natural events. While the specific actions required vary depending on the type of hazard, some general principles apply to most scenarios.

Tip 1: Understand Local Risks: Research the specific hazards prevalent in a given geographic area. Coastal regions face different risks than inland areas. Understanding these risks informs appropriate preparation strategies.

Tip 2: Develop an Emergency Plan: Establish a comprehensive plan that includes evacuation routes, communication protocols, and designated meeting points. This plan should account for all household members, including pets.

Tip 3: Assemble an Emergency Kit: Prepare a kit containing essential supplies such as water, non-perishable food, first-aid supplies, medications, flashlights, and a battery-powered radio. Regularly check and replenish these supplies.

Tip 4: Secure Property and Belongings: Implement measures to protect homes and property from potential damage. This may involve reinforcing structures, installing storm shutters, or clearing flammable vegetation around buildings.

Tip 5: Stay Informed: Monitor weather reports and official alerts from relevant agencies. Sign up for local emergency notification systems. Rapid access to accurate information is critical during an emergency.

Tip 6: Practice and Review: Regularly practice evacuation drills and review emergency plans with household members. Familiarity with procedures reduces panic and improves response times during a real event.

Tip 7: Consider Insurance Coverage: Evaluate insurance policies to ensure adequate coverage for potential damages related to relevant natural hazards.

Proactive preparation significantly enhances resilience in the face of catastrophic natural events. These measures can minimize risks, protect lives, and facilitate a more rapid and effective recovery process.

By understanding the potential risks and implementing these preparedness strategies, individuals and communities can improve their ability to withstand and recover from the impacts of extreme natural events. The following section will offer concluding thoughts on the importance of ongoing research and community-level preparedness initiatives.

1. Magnitude

Magnitude serves as a crucial quantifiable measure for assessing the strength of natural disasters, offering a framework for comparing and understanding their potential impact. While not the sole determinant of destructive capacity, magnitude provides valuable insights into the energy released during these events and plays a significant role in risk assessment and mitigation strategies.

- Earthquake Magnitude:

Earthquake magnitude, often expressed using the Richter scale or moment magnitude scale, quantifies the energy released at the earthquake’s source. A higher magnitude signifies a greater release of energy and, consequently, a stronger earthquake. The 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile, estimated at moment magnitude 9.5, exemplifies a high-magnitude event with devastating consequences, including widespread damage and a significant tsunami.

- Volcanic Eruption Magnitude:

The Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) measures the magnitude of volcanic eruptions based on factors such as the volume of ejected material, eruption column height, and duration. Larger VEI values indicate more powerful eruptions. The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, with a VEI of 7, dramatically illustrates the potential impact of a high-magnitude eruption, resulting in global climatic changes and widespread famine.

- Tropical Cyclone Magnitude:

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale categorizes hurricanes based on sustained wind speeds, representing the magnitude of these powerful storms. Higher categories correspond to stronger winds and increased potential for destruction. Hurricane Katrina in 2005, a Category 5 hurricane at its peak intensity, showcases the devastating impact of a high-magnitude tropical cyclone.

- Tsunami Magnitude:

Tsunami magnitude scales, like the Imamura-Iida scale, assess the intensity of tsunamis based on their run-up height, which is the maximum vertical height the wave reaches onshore. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, triggered by a magnitude 9.1 earthquake, exemplifies the immense destructive power of a high-magnitude tsunami, impacting multiple countries and causing widespread devastation.

Understanding magnitude across diverse natural hazard types provides critical context for assessing the potential for catastrophic consequences. While magnitude alone does not fully encompass the complexity of these events, it serves as a foundational element in evaluating their strength, contributing significantly to informed risk assessments and the development of effective mitigation strategies.

2. Intensity

While magnitude quantifies the overall energy released by a natural disaster, intensity describes the localized effects experienced at a specific point. Understanding intensity is crucial for assessing the direct impact on communities and infrastructure. Even within a single event of a given magnitude, intensity can vary significantly, leading to vastly different outcomes in affected areas. Examining the various facets of intensity provides a more granular perspective on the destructive potential of natural hazards.

- Earthquake Intensity:

Earthquake intensity, often measured using the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale, assesses the observed effects of ground shaking at a particular location. Factors influencing intensity include proximity to the epicenter, local geology, and building construction. A high-magnitude earthquake might have a low intensity far from the epicenter, while a moderate-magnitude earthquake directly beneath a city could result in high intensity and significant damage. The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, though of moderate magnitude, caused significant damage in specific areas of San Francisco due to localized variations in intensity.

- Volcanic Eruption Intensity:

Volcanic eruption intensity considers factors like the rate of magma eruption, ashfall distribution, and pyroclastic flow velocity. Even within a single eruption, intensity can vary depending on location and topography. The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, while having a lower overall magnitude than the 1815 Tambora eruption, exhibited high intensity in areas near the volcano, resulting in significant ashfall and pyroclastic flows.

- Tropical Cyclone Intensity:

Tropical cyclone intensity focuses on sustained wind speeds, central pressure, and storm surge height. Intensity can fluctuate as the storm evolves, and variations within the storm itself can result in different levels of impact across affected regions. Hurricane Harvey in 2017, while not reaching the highest wind speeds on the Saffir-Simpson scale, caused catastrophic flooding due to its slow movement and intense rainfall, demonstrating that factors beyond wind speed contribute significantly to overall intensity.

- Tsunami Intensity:

Tsunami intensity relates to the wave height, inundation distance, and flow velocity at specific coastal locations. Local topography, coastal defenses, and the shape of the coastline can influence the observed intensity. The 2011 Tohoku tsunami, while generated by a powerful earthquake, exhibited highly variable intensity along the Japanese coast, with some areas experiencing significantly greater wave heights and inundation than others.

Analyzing intensity alongside magnitude provides a more comprehensive understanding of the destructive potential of natural disasters. By considering the localized variations in intensity, disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies can be tailored to specific areas, enhancing community resilience and minimizing the impact of these powerful natural events.

3. Impact Area

The impact area of a natural disaster, defined as the geographical extent experiencing significant effects, plays a critical role in determining its overall destructive capacity. A larger impact area often correlates with increased human and economic losses. Understanding the factors influencing impact area, such as the nature of the hazard, its magnitude, and prevailing environmental conditions, is crucial for effective disaster preparedness and response. The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, while devastating the immediate vicinity, also generated a tsunami that impacted coastlines thousands of kilometers away, illustrating the potential for far-reaching consequences depending on the nature and magnitude of the event.

Consider an earthquake: While the highest intensity shaking typically occurs near the epicenter, secondary effects like landslides and tsunamis can extend the impact area significantly. The 1964 Alaska earthquake, one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded, triggered a tsunami that caused damage along the west coast of North America, highlighting the importance of considering secondary effects when evaluating the overall impact area. Similarly, large volcanic eruptions can eject vast quantities of ash and aerosols into the atmosphere, affecting air quality and potentially altering weather patterns across a broad region. The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora caused the “Year Without a Summer” due to its widespread impact on global climate.

Analyzing the impact area, in conjunction with other factors like magnitude and intensity, provides a comprehensive understanding of a natural disaster’s destructive potential. This understanding informs resource allocation for disaster relief, guides evacuation planning, and contributes to the development of mitigation strategies aimed at minimizing future losses. Mapping vulnerable populations and infrastructure within potential impact areas enables more targeted and effective disaster preparedness efforts, crucial for enhancing community resilience in the face of these powerful natural forces.

4. Duration

Duration, representing the length of time a natural disaster persists, significantly influences its overall impact and contributes to its classification as a “strongest” event. A longer duration amplifies the destructive potential, exacerbating damage, hindering rescue and recovery efforts, and increasing the strain on resources. While a short, intense burst of energy can cause significant damage, prolonged exposure to hazardous conditions often leads to more widespread and persistent consequences.

Consider flooding: While flash floods, characterized by a rapid onset and short duration, can be devastating, prolonged flooding, such as that experienced during the 2011 Mississippi River floods, often leads to more extensive damage to infrastructure, displacement of populations, and economic disruption. The extended duration allows floodwaters to saturate the ground, compromise building foundations, and disrupt transportation networks for extended periods, compounding the overall impact. Similarly, protracted droughts, like the multi-year drought in the Sahel region of Africa, exert a cumulative toll on agriculture, water resources, and human health, leading to widespread food insecurity and societal instability.

The duration of wildfires, influenced by factors like fuel availability, weather conditions, and topography, directly impacts the extent of burned areas and the severity of ecological damage. The 2020 Australian bushfires, characterized by an unusually long fire season, resulted in widespread habitat loss, significant air pollution, and prolonged disruption to communities. Understanding the factors influencing the duration of natural hazards is crucial for developing effective mitigation and response strategies. Predictive models that incorporate duration, along with other factors like intensity and impact area, provide valuable insights for resource allocation, evacuation planning, and post-disaster recovery efforts. The ability to anticipate the duration of a hazard allows for better-informed decision-making and ultimately contributes to minimizing the long-term consequences of these powerful natural events.

5. Frequency

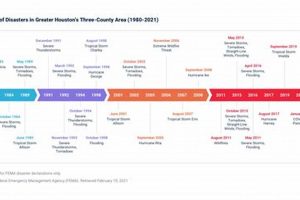

Frequency, representing the rate at which natural disasters of a given magnitude occur, is a critical factor in understanding and mitigating risk. While a single, exceptionally powerful event can cause catastrophic damage, frequent occurrences of less intense events can also contribute significantly to cumulative losses over time. Analyzing frequency alongside magnitude helps assess long-term risks and prioritize mitigation efforts. Understanding the statistical probability of different magnitudes of events is essential for developing effective disaster preparedness strategies and building resilient communities.

- Recurrence Intervals:

Recurrence intervals estimate the average time between events of a specific magnitude. For instance, a 100-year flood has a 1% chance of occurring in any given year. While this doesn’t guarantee it will only happen once every 100 years, it provides a statistical framework for assessing risk. Understanding recurrence intervals is crucial for land-use planning, infrastructure design, and insurance pricing. Building codes often incorporate these probabilities to ensure structures can withstand events of a certain recurrence interval.

- Temporal Clustering:

Natural disasters sometimes exhibit temporal clustering, meaning that events occur more frequently within certain periods. This can be due to underlying climate patterns, geological processes, or other factors. For example, El Nio events can increase the likelihood of certain types of disasters in specific regions, while periods of increased seismic activity can lead to a higher frequency of earthquakes. Recognizing temporal clustering helps anticipate periods of heightened risk and adjust preparedness strategies accordingly.

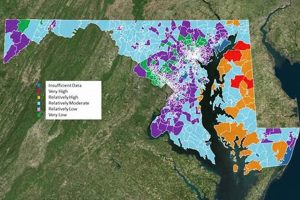

- Geographic Distribution:

Certain geographic areas are more prone to specific types of natural disasters due to their location and environmental conditions. Coastal regions are susceptible to hurricanes and tsunamis, while areas near tectonic plate boundaries experience more frequent earthquakes. Understanding the geographic distribution of hazards is fundamental for risk assessment and land-use planning. Population density in high-risk areas increases the potential human impact of frequent events, even if their individual magnitudes are relatively low.

- Impact on Mitigation Strategies:

The frequency of events significantly influences the design and implementation of mitigation strategies. Frequent, low-magnitude events might necessitate different mitigation measures compared to rare, high-magnitude events. For example, regular flooding might require improved drainage systems and flood-resistant construction, while infrequent but powerful earthquakes necessitate robust building codes and early warning systems. Balancing the cost of mitigation measures with the frequency and potential impact of events is a crucial aspect of disaster risk reduction.

Analyzing the frequency of natural disasters in conjunction with their magnitude provides a comprehensive view of long-term risk. This understanding informs resource allocation for mitigation efforts, guides community planning, and contributes to developing sustainable strategies for minimizing the cumulative impacts of both frequent, low-magnitude events and rare, high-magnitude catastrophes. Recognizing the interplay between frequency and magnitude is essential for building resilience and safeguarding communities against the ongoing threat of natural hazards.

6. Human Impact

Human impact, encompassing casualties, economic losses, and societal disruption, forms a critical dimension in assessing the overall strength of a natural disaster. While geophysical magnitude scales quantify the energy released, the human cost ultimately defines the disaster’s severity within a societal context. A high-magnitude event in an unpopulated area might register as geophysically significant but have minimal human impact compared to a lower-magnitude event striking a densely populated region. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, though not the strongest in terms of pure magnitude, resulted in immense devastation and loss of life due to the city’s population density and building practices at the time, demonstrating the significance of human factors in shaping disaster impact.

Furthermore, human activities can exacerbate the effects of natural disasters. Deforestation increases the risk of landslides, while urbanization and coastal development amplify the impact of storm surges and flooding. Climate change, driven by human activities, is projected to increase the frequency and intensity of certain types of extreme weather events, further highlighting the complex interplay between human actions and the consequences of natural hazards. The increasing intensity and frequency of hurricanes impacting coastal communities demonstrate this connection, as warmer ocean temperatures fuel stronger storms and rising sea levels exacerbate coastal flooding.

Understanding the human impact of natural disasters is crucial for developing effective mitigation and response strategies. Vulnerability assessments, which consider factors like population density, infrastructure resilience, and socioeconomic conditions, can inform targeted interventions aimed at reducing risk. Early warning systems, coupled with effective evacuation plans and disaster preparedness education, play a vital role in minimizing casualties and societal disruption. The success of early warning systems in reducing casualties during recent tsunamis underscores the importance of incorporating human factors into disaster preparedness planning. Ultimately, recognizing the human dimension of natural disasters is essential for building more resilient communities and minimizing the societal cost of these inevitable events.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding high-impact natural events, providing concise and informative responses.

Question 1: How are the “strongest” natural disasters determined?

Assessing the strength of natural disasters involves considering various factors, including magnitude (energy released), intensity (localized effects), impact area, duration, frequency, and human impact (casualties, economic losses, and societal disruption). No single metric defines “strongest,” as the relative importance of these factors depends on the specific hazard and context.

Question 2: Is it possible to predict catastrophic natural events?

While precise prediction remains a challenge, scientific advancements have improved forecasting capabilities for certain hazards. Probabilistic models, based on historical data and real-time monitoring, provide estimates of likelihood and potential impact, enabling proactive preparedness measures. Predicting the precise timing and location of events, however, often remains beyond current capabilities.

Question 3: What role does climate change play in the intensity and frequency of natural disasters?

Scientific evidence suggests that climate change is influencing the intensity and frequency of certain extreme weather events. Warmer ocean temperatures contribute to more powerful hurricanes, while changing precipitation patterns exacerbate floods and droughts. Understanding the link between climate change and natural hazards is crucial for developing effective adaptation and mitigation strategies.

Question 4: What measures can be taken to mitigate the impact of natural disasters?

Mitigation strategies encompass a range of approaches, including land-use planning, infrastructure improvements, early warning systems, and community education. Building codes designed to withstand specific hazards, coupled with effective evacuation plans, can significantly reduce the impact of catastrophic events. Investing in resilient infrastructure and promoting community preparedness are crucial for minimizing losses.

Question 5: What are the long-term consequences of catastrophic natural events?

Long-term consequences can include displacement of populations, economic disruption, environmental damage, and psychological trauma. Recovery from catastrophic events often requires years of sustained effort and investment. Understanding the long-term impacts is crucial for developing comprehensive recovery plans that address both immediate needs and long-term rebuilding efforts.

Question 6: How can individuals contribute to disaster preparedness?

Individual preparedness measures include developing a family emergency plan, assembling an emergency kit, staying informed about potential hazards, and participating in community preparedness initiatives. Understanding local risks and taking proactive steps to prepare can significantly enhance individual and community resilience.

Preparedness and mitigation are crucial for reducing the impact of catastrophic natural events. Understanding the multifaceted nature of these events, from geophysical processes to human impacts, is essential for building more resilient communities.

Further exploration of specific hazard types and mitigation strategies will follow in the subsequent sections.

Understanding Extreme Natural Events

Characterizing a single event as the definitively “strongest natural disaster” presents inherent complexities. This exploration has highlighted the multifaceted nature of catastrophic events, emphasizing the interplay of magnitude, intensity, impact area, duration, frequency, and human impact. Each factor contributes uniquely to an event’s overall destructive potential, making direct comparisons challenging. Focusing solely on geophysical magnitude overlooks the significant role of human factors in shaping disaster consequences. Vulnerability, driven by population density, infrastructure resilience, and socioeconomic conditions, significantly influences the human cost of natural hazards. While a high-magnitude event in a sparsely populated area might register as geophysically significant, its societal impact can pale in comparison to a less powerful event striking a densely populated region.

Continued research into the underlying mechanisms driving these powerful events remains crucial for refining predictive capabilities and developing more effective mitigation strategies. Investing in resilient infrastructure, strengthening early warning systems, and promoting community preparedness represent essential steps towards minimizing future losses. Ultimately, understanding the complex interplay of geophysical forces and human vulnerability is paramount for building a more resilient future in the face of inevitable natural hazards. Acknowledging the multifaceted nature of these events and embracing a proactive approach to preparedness are crucial for safeguarding communities and mitigating the far-reaching consequences of extreme natural events.