No state is entirely immune to the forces of nature. While some regions experience certain hazards less frequently than others, every area of the United States is susceptible to some type of natural event, whether it be wildfires, floods, earthquakes, tornadoes, hurricanes, droughts, or extreme temperature fluctuations. For example, a state might have a low risk of hurricanes but still face substantial threats from wildfires or winter storms.

Understanding regional variations in hazard risk is crucial for effective disaster preparedness and mitigation. Building codes, infrastructure planning, and emergency response protocols must be tailored to address the specific threats faced by a given community. Historically, communities have adapted to recurring natural events, but changing climate patterns are influencing both the frequency and intensity of these occurrences, necessitating ongoing adjustments to mitigation strategies. Accurate risk assessment helps individuals, communities, and governments prioritize resources and implement protective measures, thereby minimizing potential loss of life and property.

This discussion will further explore the geographical distribution of various natural hazards across the United States, highlighting regions with lower risks for specific events and discussing the factors contributing to their relative safety. It will also examine the ongoing efforts to improve predictive modeling and enhance community resilience in the face of a changing climate.

Tips for Understanding Natural Hazard Risks

While no location is entirely free from natural hazards, understanding regional variations in risk is crucial for effective preparedness. These tips offer guidance for assessing and mitigating potential threats.

Tip 1: Research Local Hazards: Investigate the specific natural hazards prevalent in a given area. Consult resources like the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for historical data and risk assessments.

Tip 2: Understand Building Codes: Local building codes often reflect regional hazard risks. Familiarize yourself with these regulations to ensure structures are adequately designed to withstand potential events.

Tip 3: Prepare an Emergency Kit: Assemble supplies for various scenarios, including water, non-perishable food, first-aid supplies, and communication devices. Regularly check and replenish these items.

Tip 4: Develop an Evacuation Plan: Establish clear evacuation routes and procedures for different types of emergencies. Coordinate with family members or housemates to ensure everyone understands the plan.

Tip 5: Stay Informed: Monitor weather alerts and official communications from local authorities. Sign up for emergency notification systems to receive timely updates on developing situations.

Tip 6: Consider Insurance Coverage: Review insurance policies to ensure adequate coverage for potential natural disasters. Understand policy limitations and exclusions related to specific events.

Tip 7: Engage in Community Preparedness: Participate in community-level preparedness initiatives and drills. Collaboration strengthens community resilience and improves overall response effectiveness.

By taking these proactive steps, individuals and communities can significantly enhance their preparedness for natural hazards, minimize potential losses, and foster greater resilience.

The subsequent section will offer further resources and tools for comprehensive disaster preparedness planning.

1. Nowhere is entirely safe.

The assertion “Nowhere is entirely safe” directly refutes the premise of a disaster-immune state. It underscores the inherent vulnerability of all geographic locations to natural hazards, dismantling the misconception that any region can entirely escape the forces of nature. This understanding forms the foundation for effective disaster preparedness and mitigation strategies.

- Geological Instability

The Earth’s crust is constantly shifting, leading to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunamis. While certain regions experience these events more frequently, no location is entirely exempt from geological activity. For instance, while the West Coast of the United States is known for seismic activity, less frequent earthquakes occur in other areas, demonstrating the widespread nature of this hazard.

- Hydro-meteorological Events

Weather-related hazards, such as hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, blizzards, and droughts, impact every region differently. Coastal areas are susceptible to hurricanes, while inland regions can experience severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. Even typically arid regions can face devastating flash floods. The variability of these events reinforces the concept that no location is completely safe.

- Wildfires

Wildfires are a significant threat in areas with dry vegetation, and their occurrence is influenced by factors like temperature, wind patterns, and human activity. While prevalent in the western United States, wildfires also occur in other regions, including the Southeast, highlighting the widespread vulnerability to this hazard.

- Changing Climate Patterns

Climate change influences the frequency and intensity of various natural hazards. Rising sea levels exacerbate coastal flooding, while changing precipitation patterns contribute to more intense droughts and floods. These shifting patterns emphasize the dynamic nature of risk and underscore the need for adaptive preparedness strategies in all locations.

These various facets of natural hazards demonstrate that all locations face some degree of risk. Accepting this reality allows for a more proactive approach to disaster preparedness, focusing on mitigating potential impacts rather than searching for a nonexistent risk-free zone. Understanding local hazards and implementing appropriate safety measures are crucial for building resilience in any location.

2. All states have risks.

The statement “All states have risks” directly counters the notion of a disaster-free state. It emphasizes the universal exposure to natural hazards, dismantling the misconception of absolute safety. Understanding this reality is crucial for effective risk assessment and preparedness. This section explores specific examples of how different states face distinct natural hazard risks.

- California: Earthquakes, Wildfires, and Drought

California experiences significant seismic activity along major fault lines, making earthquakes a constant threat. The state’s dry climate and abundant vegetation create conditions ripe for wildfires, especially during prolonged periods of drought. These combined risks highlight California’s vulnerability to multiple, compounding natural hazards.

- Florida: Hurricanes and Flooding

Florida’s extensive coastline and low-lying topography make it highly susceptible to hurricanes and associated flooding. The state’s vulnerability is further amplified by rising sea levels, increasing the risk of coastal erosion and storm surge inundation.

- Texas: Hurricanes, Tornadoes, and Flooding

Texas faces the combined threat of hurricanes along its Gulf Coast and tornadoes in its interior regions. The state’s variable climate also leads to periods of severe drought punctuated by intense rainfall events, resulting in significant flooding risks.

- Midwest States: Tornadoes, Flooding, and Blizzards

The Midwest is known as “Tornado Alley” due to the frequent occurrence of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. The region is also susceptible to river flooding and winter blizzards, presenting a diverse range of natural hazard risks.

These examples illustrate the diverse range of natural hazards faced by different states. The absence of a disaster-free state underscores the need for comprehensive risk assessment and tailored preparedness strategies based on regional vulnerabilities. Recognizing inherent risks enables proactive mitigation and planning, enhancing resilience across diverse geographical locations.

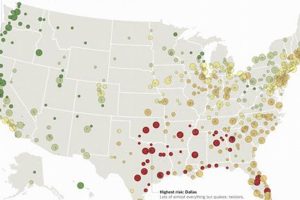

3. Risk varies by location.

The concept of variable risk directly refutes the idea of a disaster-immune state. While all locations face some degree of natural hazard risk, the specific threats, frequency, and intensity vary significantly based on geography, climate, and geological factors. Understanding these regional variations is essential for effective disaster preparedness and mitigation.

- Coastal Regions

Coastal areas are inherently vulnerable to hurricanes, storm surges, and coastal erosion. The intensity of these hazards is influenced by factors such as proximity to warm ocean currents, prevailing wind patterns, and shoreline topography. For example, the Gulf Coast is particularly susceptible to hurricanes, while the Pacific Coast faces threats from tsunamis.

- Seismic Zones

Regions located along tectonic plate boundaries experience heightened earthquake risk. The frequency and magnitude of earthquakes are determined by geological factors such as fault lines and the rate of plate movement. The West Coast of the United States, situated along the Pacific Ring of Fire, is a prime example of a high-risk seismic zone.

- Floodplains

Areas located in floodplains are at increased risk of flooding due to proximity to rivers and other bodies of water. The extent and severity of flooding are influenced by factors such as rainfall intensity, river discharge rates, and the presence of flood control infrastructure. Riverine communities throughout the United States face varying degrees of flood risk depending on local conditions.

- Wildfire-Prone Areas

Regions with dry climates and abundant vegetation are susceptible to wildfires. The risk is further exacerbated by factors such as temperature, wind patterns, and human activity. The western United States, particularly California, experiences frequent and intense wildfires due to its Mediterranean climate.

The variability of natural hazard risks across different locations reinforces the absence of a disaster-free state. Effective disaster preparedness requires a location-specific approach, focusing on the prevalent hazards in a given area. Understanding regional vulnerabilities allows for targeted mitigation efforts and the development of tailored preparedness strategies, enhancing community resilience in the face of diverse natural threats.

4. Preparedness is crucial.

The crucial nature of preparedness directly counters the flawed notion of a disaster-immune state. Since no location is entirely free from natural hazards, preparedness becomes paramount for mitigating potential impacts and ensuring community resilience. The absence of a risk-free zone necessitates a proactive approach, emphasizing planning, resource allocation, and community education to minimize vulnerabilities and enhance recovery capabilities.

Consider the example of a coastal community facing hurricane threats. While the precise timing and intensity of a hurricane remain uncertain, the inherent vulnerability of the location necessitates preparedness measures. These measures might include developing evacuation plans, reinforcing building codes, establishing early warning systems, and conducting community-wide drills. Similarly, communities in earthquake-prone regions must prioritize seismic-resistant construction, secure infrastructure, and public awareness campaigns regarding earthquake safety protocols. These proactive measures, implemented in advance of any specific event, significantly reduce potential losses and facilitate faster recovery.

The practical significance of preparedness lies in its ability to transform vulnerability into resilience. By acknowledging inherent risks and implementing appropriate mitigation strategies, communities can effectively manage the impacts of natural hazards. Preparedness empowers individuals and communities to take ownership of their safety, fostering a culture of proactive risk reduction rather than relying on the misconception of a disaster-free location. This shift in perspective, from seeking an impossible safe haven to embracing preparedness, is essential for navigating the inherent uncertainties of natural events and building resilient communities capable of withstanding and recovering from future disasters.

5. Mitigation matters.

Mitigation, the act of reducing the severity and impact of potential hazards, holds paramount importance given the reality that no state is entirely immune to natural disasters. Acknowledging the inevitability of natural events necessitates a proactive approach, emphasizing mitigation strategies to minimize vulnerabilities and enhance community resilience. Effective mitigation transforms a reactive approach to disaster management into a proactive one, reducing long-term costs and preserving lives and property.

- Building Codes and Infrastructure Design

Stringent building codes and resilient infrastructure design play a crucial role in mitigating the impact of natural hazards. Seismic-resistant construction in earthquake-prone areas, elevated structures in floodplains, and wind-resistant designs in hurricane-prone regions demonstrably reduce structural damage and protect lives. For instance, enforcing stricter building codes in coastal areas can significantly lessen the devastation caused by hurricanes.

- Land Use Planning and Zoning

Strategic land use planning and zoning regulations can direct development away from high-risk areas, minimizing exposure to hazards. Restricting development in floodplains, wildfire-prone areas, and coastal erosion zones reduces the potential for property damage and loss of life. For example, implementing stringent zoning regulations in coastal communities can limit development in vulnerable areas, minimizing exposure to storm surge and coastal erosion.

- Natural Resource Management

Sustainable natural resource management practices, such as forest management and wetland preservation, contribute significantly to hazard mitigation. Proper forest management reduces the risk of catastrophic wildfires, while preserving wetlands provides natural flood control and buffers against storm surge. For example, controlled burns and forest thinning reduce fuel loads, mitigating the intensity and spread of wildfires.

- Public Awareness and Education

Public awareness campaigns and educational programs empower individuals and communities to take proactive steps to protect themselves and their property. Educating the public about specific hazards, preparedness measures, and evacuation procedures enhances community resilience and promotes a culture of safety. For example, community-wide drills and public service announcements regarding earthquake preparedness can significantly improve response effectiveness during an actual event.

These mitigation strategies, while diverse in their implementation, share a common goal: reducing the impact of inevitable natural hazards. By proactively addressing vulnerabilities, communities can minimize losses, enhance resilience, and foster a culture of preparedness. The absence of a disaster-free state underscores the vital role of mitigation in building safer and more resilient communities across all regions.

6. Understand local hazards.

Understanding local hazards is paramount given the reality that no state is entirely immune to natural disasters. The misconception of a disaster-free location necessitates a shift in focus from seeking an impossible safe haven to proactively understanding and mitigating regionally specific risks. This understanding forms the cornerstone of effective disaster preparedness, enabling individuals and communities to take ownership of their safety and build resilience in the face of inevitable natural events.

The geographical variability of natural hazards underscores the critical need to understand local risks. Coastal regions face threats from hurricanes and storm surge, while inland areas may be more susceptible to tornadoes, wildfires, or winter storms. Seismic zones experience heightened earthquake risk, while communities situated near rivers or in floodplains face increased flood vulnerability. This diversity of threats necessitates a localized approach to preparedness, emphasizing the importance of understanding the specific hazards prevalent in a given area. For example, residents in coastal Florida should prioritize hurricane preparedness, while those in California must focus on earthquake and wildfire safety. Ignoring local hazards can have devastating consequences, as evidenced by the significant losses experienced in communities unprepared for specific threats.

The practical significance of understanding local hazards lies in its ability to empower proactive mitigation and preparedness. This understanding informs decisions regarding building codes, land use planning, infrastructure development, and emergency response protocols. By tailoring these measures to address specific local threats, communities can effectively reduce their vulnerability and enhance their resilience. Furthermore, understanding local hazards empowers individuals to make informed decisions about their own safety, including developing personal preparedness plans, securing adequate insurance coverage, and actively participating in community-wide preparedness initiatives. Ultimately, recognizing that no state is entirely free from natural disasters underscores the critical importance of understanding local hazards as the foundation for building safer, more resilient communities.

Frequently Asked Questions about Natural Disasters

This FAQ section addresses common misconceptions regarding the existence of a disaster-free state and provides clarity on natural hazard risks and preparedness.

Question 1: Is there any state completely free from natural disasters?

No. Every state in the United States is susceptible to some type of natural hazard, whether it’s hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes, wildfires, floods, or winter storms. The frequency and intensity of these events vary by location, but no region is entirely immune.

Question 2: Which states have the lowest risk of natural disasters?

Quantifying “lowest risk” is complex, as different states are vulnerable to different hazards. States like Michigan, Illinois, and Ohio experience fewer hurricanes than coastal states, but they still face risks from tornadoes, floods, and winter storms. Focusing on preparedness for relevant hazards is more effective than seeking a hypothetically “low-risk” location.

Question 3: If all states have risks, why do some areas seem safer than others?

Perceptions of safety often reflect the infrequency of high-impact events. A region might experience minor flooding regularly but be perceived as safer than a region with infrequent but catastrophic hurricanes. Understanding the full spectrum of potential hazards, not just the most dramatic ones, is crucial for accurate risk assessment.

Question 4: Does moving to a different state guarantee safety from natural disasters?

Relocating does not eliminate natural hazard risk. Each region faces its own unique set of threats. Moving from a hurricane-prone area to a seismically active zone simply exchanges one set of risks for another. Preparedness remains crucial regardless of location.

Question 5: How can one determine the specific risks for a particular location?

Resources like the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and state geological surveys provide detailed information on regional hazards, historical data, and risk assessments. Consulting these resources offers valuable insights for understanding location-specific threats.

Question 6: What is the most effective way to mitigate natural disaster risks?

Proactive mitigation and preparedness are the most effective strategies. This includes understanding local hazards, strengthening building codes, developing evacuation plans, securing appropriate insurance coverage, and actively participating in community-level preparedness initiatives.

Preparedness, rather than seeking a nonexistent risk-free zone, is the key to mitigating the impacts of natural disasters. Understanding local hazards and implementing appropriate safety measures are crucial for enhancing resilience in any location.

The following section will delve deeper into specific preparedness strategies for various natural hazards.

Conclusion

Exploration of the question “what state does not have natural disasters” reveals a fundamental truth: no region in the United States is entirely safe from the forces of nature. While specific hazards vary by location, every state faces some degree of risk, whether from hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes, wildfires, floods, or other natural events. The misconception of a disaster-free zone underscores the critical importance of shifting focus from seeking an impossible safe haven to embracing proactive preparedness and mitigation strategies.

Effective disaster management hinges on acknowledging inherent vulnerabilities and tailoring mitigation efforts to address regionally specific threats. Strengthening building codes, implementing strategic land use planning, investing in resilient infrastructure, and fostering a culture of preparedness are crucial steps toward building safer, more resilient communities. Continued investment in research, improved forecasting capabilities, and enhanced public awareness campaigns will further empower communities to effectively navigate the inevitable challenges posed by natural hazards. Ultimately, recognizing universal vulnerability is the first step toward building a more resilient nation, prepared to withstand and recover from the impacts of natural disasters, regardless of location.