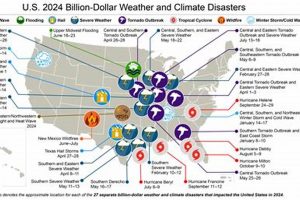

No state is entirely free from the risk of natural hazards. While some regions experience certain hazards less frequently than others, all areas of the United States are susceptible to some type of natural event, whether it’s severe storms, flooding, wildfires, earthquakes, or other potential dangers. For example, while a state might have a low risk of hurricanes, it could still be prone to blizzards or droughts. The idea of a risk-free location is a misconception.

Understanding regional variations in hazard risk is crucial for effective disaster preparedness and mitigation. Accurately assessing the specific threats a region faces allows for informed decision-making regarding building codes, infrastructure development, and resource allocation for emergency response. This knowledge empowers individuals, communities, and governments to minimize potential damage and protect lives and property. Historically, areas perceived as less hazardous have sometimes seen rapid population growth, increasing vulnerability when an infrequent event eventually occurs.

This discussion will explore the types of natural hazards that impact different regions of the United States, examining the factors that contribute to these risks and highlighting the importance of proactive planning and preparation. Further sections will address specific mitigation strategies and resources available to communities facing diverse threats.

Tips for Understanding Natural Hazard Risks

While no location is entirely immune to natural hazards, understanding regional risks is crucial for effective preparedness. These tips offer guidance on assessing and mitigating potential threats.

Tip 1: Research Local Hazards: Consult official sources like the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Weather Service to identify the specific hazards prevalent in a given area. This information is essential for developing targeted preparedness plans.

Tip 2: Consider Hazard History: Past occurrences offer valuable insights into future risks. Researching historical records of earthquakes, floods, wildfires, and other events helps gauge potential recurrence and severity.

Tip 3: Evaluate Building Codes and Land Use: Stringent building codes and informed land-use planning are critical for minimizing damage. Regulations designed to withstand specific threats, such as seismic activity or high winds, are essential safeguards.

Tip 4: Develop an Emergency Plan: A comprehensive plan outlining evacuation routes, communication protocols, and necessary supplies is vital for any household or community. Regularly review and update this plan to ensure its effectiveness.

Tip 5: Invest in Hazard-Resistant Construction: When building or renovating, consider incorporating features that enhance resilience against relevant hazards. This might include reinforced foundations, storm shutters, or fire-resistant materials.

Tip 6: Secure Insurance Coverage: Adequate insurance coverage is crucial for financial recovery after a disaster. Evaluate policies to ensure they address specific regional risks, such as flood or earthquake damage.

Tip 7: Stay Informed: Monitor weather alerts and official announcements from local authorities. Timely information enables proactive responses to impending threats, potentially minimizing damage and ensuring safety.

By understanding and addressing regional hazard risks, communities can significantly reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience in the face of natural events. Proactive planning and informed decision-making are key to mitigating potential damage and safeguarding lives and property.

The following section will offer a detailed examination of specific natural hazards and regional vulnerabilities across the United States.

1. Nowhere is entirely safe.

The statement “Nowhere is entirely safe” directly refutes the premise of a disaster-free state. While relative safety exists, absolute immunity from natural hazards is a misconception. Every geographic location faces potential threats, whether geological, meteorological, or hydrological. The absence of a specific hazard in a particular region does not equate to overall safety. For instance, a state with minimal earthquake risk might still experience severe storms, flooding, or wildfires. Focusing solely on one hazard type ignores the broader spectrum of potential threats. Consequently, the search for a “safe” state becomes a pursuit of a non-existent ideal.

This understanding has significant practical implications. It underscores the importance of comprehensive risk assessment, encompassing all potential hazards, rather than focusing on a single threat. For example, building codes should reflect not only seismic activity but also wind loads, fire resistance, and potential flood levels. Similarly, emergency preparedness plans must address diverse scenarios, including evacuations, sheltering in place, and access to emergency supplies. Real-life examples, such as communities devastated by unexpected hazards, highlight the dangers of complacency based on a perceived absence of specific risks. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan, a region considered relatively safe from such large-scale events, serves as a stark reminder of the unforeseen nature of natural hazards.

Recognizing that “Nowhere is entirely safe” is crucial for fostering a proactive and comprehensive approach to disaster preparedness and mitigation. Rather than seeking an illusory risk-free location, efforts should focus on understanding and mitigating the specific hazards present in any given area. This includes investing in resilient infrastructure, developing robust emergency plans, and promoting community awareness and education. Accepting inherent risk allows for realistic and effective strategies to minimize vulnerability and enhance overall safety, regardless of location.

2. Risk varies geographically.

The assertion “risk varies geographically” directly challenges the notion of a disaster-free state. Understanding the spatial distribution of natural hazards is fundamental to refuting the idea that any location is entirely immune to risk. This concept highlights the influence of geographical factors on hazard susceptibility, emphasizing the need for region-specific preparedness strategies.

- Coastal Hazards:

Coastal regions face elevated risks from hurricanes, storm surges, and tsunamis. The Gulf Coast, for example, experiences frequent hurricane landfalls, while the Pacific Northwest is susceptible to tsunamis. Proximity to the ocean and specific geological features influence the intensity and frequency of these events. Consequently, building codes in coastal areas often mandate hurricane straps and elevated foundations, reflecting the specific regional hazard profile. The idea of a “safe” coastal state ignores the inherent vulnerability to these geographically determined threats.

- Seismic Activity:

Earthquake risk is concentrated along tectonic plate boundaries. California, situated along the San Andreas Fault, experiences frequent seismic activity, while the central United States has significantly lower earthquake risk. Building codes in earthquake-prone regions require specific structural reinforcements to withstand ground shaking. The geographical distribution of seismic risk demonstrates that no state is uniformly safe from this hazard.

- Wildfire Risk:

Areas with dry climates and abundant vegetation, such as California and the western United States, face higher wildfire risks. Factors like topography and wind patterns influence fire behavior and spread. Mitigation strategies in these areas include prescribed burns and defensible space around structures. The geographical concentration of wildfire risk reinforces the variability of hazards across different states.

- Inland Flooding:

Inland regions, particularly those near rivers and floodplains, are susceptible to flooding from heavy rainfall and snowmelt. The Midwest, for example, experiences frequent river flooding, while mountainous areas face risks from flash floods. Infrastructure development and land-use planning play crucial roles in mitigating flood risks in these areas. The geographical variability of inland flooding demonstrates that even states far from coastlines are not immune to natural hazards.

The geographical distribution of these hazards underscores the impossibility of a disaster-free state. Each region faces a unique combination of threats, requiring tailored preparedness and mitigation strategies. The search for a universally safe location ignores the fundamental principle that risk varies geographically.

3. Preparedness is crucial.

The crucial nature of preparedness directly counters the misconception of a disaster-free state. Since no location is entirely immune to natural hazards, preparation becomes paramount for mitigating potential impacts. Regardless of geographical location, developing and implementing comprehensive preparedness strategies is essential for safeguarding lives and property. This proactive approach acknowledges the inherent risks associated with natural events and emphasizes the importance of readiness rather than the pursuit of a risk-free environment.

- Individual Preparedness:

Individual preparedness forms the foundation of community resilience. Developing personal emergency plans, assembling essential supplies, and staying informed about potential threats empower individuals to respond effectively during a disaster. Actions like creating evacuation kits, establishing communication protocols with family members, and understanding local warning systems are crucial regardless of the specific hazards a region faces. This individual-level preparedness reduces reliance on external resources during emergencies, enhancing self-sufficiency and overall community resilience. Examples include individuals who, due to their preparedness, successfully evacuated before Hurricane Katrina or sheltered safely during wildfires. These cases demonstrate the life-saving potential of individual preparedness, regardless of whether a state is perceived as “safe” from specific hazards.

- Community Preparedness:

Community-level preparedness amplifies the effectiveness of individual efforts. Coordinated planning, resource allocation, and communication systems enhance a community’s capacity to respond to and recover from disasters. Establishing evacuation centers, organizing volunteer networks, and conducting regular drills are crucial aspects of community preparedness. Examples include communities that successfully implemented early warning systems for flash floods or established neighborhood support networks during prolonged power outages. These collective actions demonstrate the importance of community preparedness, irrespective of the specific hazards a state might face. The misconception of a disaster-free state can hinder the development of robust community-level preparedness, increasing vulnerability when a disaster eventually strikes.

- Infrastructure Resilience:

Investing in resilient infrastructure is a critical component of preparedness. Designing and constructing buildings, bridges, and other critical infrastructure to withstand anticipated hazards minimizes damage and disruption during disasters. Examples include incorporating seismic design features in earthquake-prone regions, constructing levees for flood protection, and burying power lines to mitigate wind damage. These measures enhance a community’s ability to maintain essential services during and after a natural event. The belief in a disaster-free state can lead to complacency in infrastructure development, potentially resulting in greater damage and disruption when hazards occur. Resilient infrastructure serves as a critical line of defense, regardless of specific regional risks.

- Early Warning Systems:

Effective early warning systems are crucial for timely evacuations and protective actions. Advanced meteorological and geological monitoring technologies provide crucial information about impending threats, enabling communities to prepare and respond proactively. Examples include tsunami warning systems in coastal regions, earthquake early warning systems, and sophisticated weather radar networks. These systems provide critical lead time for individuals and communities to take appropriate actions, such as seeking higher ground during floods or sheltering in place during tornadoes. The existence of advanced warning systems does not negate the need for preparedness. Even with timely warnings, individual and community-level readiness remains essential for effective response and minimizing impacts. The misconception of a disaster-free state can undermine the importance of these warning systems, leading to delayed or inadequate responses.

These interconnected aspects of preparedness highlight the proactive nature of effective disaster management. Rather than seeking a hypothetical disaster-free location, preparedness acknowledges inherent risk and emphasizes readiness. This proactive approach, encompassing individual actions, community-level planning, infrastructure development, and early warning systems, is crucial for mitigating the impacts of natural hazards regardless of geographic location. The belief in a disaster-free state can lead to a false sense of security, hindering the implementation of these essential preparedness measures and increasing vulnerability when a disaster eventually occurs.

4. Mitigation reduces impact.

The principle of “mitigation reduces impact” directly challenges the notion of a disaster-free state. Recognizing that all locations face potential hazards underscores the importance of proactive mitigation measures to minimize the consequences of these events. Rather than seeking a non-existent risk-free zone, focusing on mitigation strategies offers a practical and effective approach to enhancing community resilience and reducing vulnerabilities, regardless of geographic location.

- Land-Use Planning:

Strategic land-use planning plays a critical role in reducing the impact of natural hazards. Restricting development in high-risk areas, such as floodplains and coastal zones, can significantly limit exposure to potential dangers. Implementing zoning regulations that incorporate hazard mapping and risk assessments ensures that development occurs in safer locations. For example, communities that restrict construction in flood-prone areas experience less flood damage during heavy rainfall events. This proactive approach to land use, rather than seeking a hazard-free state, recognizes inherent risks and minimizes their potential consequences. By guiding development away from vulnerable areas, land-use planning significantly reduces the overall impact of natural events.

- Building Codes and Standards:

Enforcing stringent building codes and standards enhances the resilience of structures to withstand natural hazards. Regulations that mandate specific design features, such as reinforced foundations in earthquake-prone regions or hurricane straps in coastal areas, significantly reduce structural damage during these events. For instance, buildings constructed to withstand high wind speeds experience less damage during hurricanes compared to structures built to lower standards. These building codes, rather than seeking a disaster-immune location, acknowledge potential risks and mitigate their impact through robust construction practices. By incorporating hazard-resistant design features, building codes and standards contribute substantially to reducing the overall impact of natural events.

- Infrastructure Improvements:

Investing in infrastructure improvements designed to mitigate specific hazards can substantially reduce their impact. Constructing levees for flood protection, reinforcing bridges to withstand seismic activity, and burying power lines to minimize wind damage are examples of proactive mitigation measures. For example, communities with robust levee systems experience less disruption from river flooding compared to areas with inadequate flood control infrastructure. This focus on infrastructure improvements, rather than the pursuit of a hazard-free state, recognizes the importance of investing in protective measures to minimize the consequences of natural events. By enhancing infrastructure resilience, communities can effectively reduce the overall impact of disasters.

- Natural Resource Management:

Effective natural resource management plays a crucial role in mitigating the impact of certain natural hazards. Maintaining healthy forests through controlled burns and proper land management practices can reduce the severity of wildfires. Restoring coastal wetlands provides a natural buffer against storm surges and erosion, minimizing the impact of hurricanes. For example, coastal communities with restored wetland areas experience less coastal erosion during storms compared to areas with degraded wetlands. This focus on natural resource management, rather than seeking a disaster-immune state, recognizes the protective role of healthy ecosystems in mitigating the impact of natural events. By preserving and restoring natural resources, communities can effectively reduce their vulnerability to specific hazards.

These mitigation measures demonstrate a proactive approach to disaster management that focuses on reducing impact rather than seeking an impossible disaster-free state. By implementing these strategies, communities can effectively minimize their vulnerability to natural hazards, regardless of their geographic location. The misconception of a disaster-free state can hinder the implementation of these essential mitigation measures, increasing overall risk and potential damage. Embracing the principle of “mitigation reduces impact” empowers communities to take proactive steps toward enhancing resilience and safeguarding lives and property in the face of inevitable natural events.

5. Building codes matter.

The statement “Building codes matter” directly refutes the concept of a disaster-free state. While no location is entirely immune to natural hazards, robust building codes significantly mitigate the impact of these events. Building codes represent a crucial component of disaster preparedness, recognizing that structures designed and constructed to withstand specific hazards experience less damage and contribute to enhanced community resilience. This proactive approach, focusing on structural integrity rather than seeking a risk-free location, underscores the practical significance of building codes in reducing vulnerability to natural disasters.

The effectiveness of building codes in mitigating disaster impacts is evident in numerous real-world scenarios. Following Hurricane Andrew in 1992, updated building codes in Florida, incorporating stricter wind resistance requirements, resulted in significantly less structural damage during subsequent hurricanes. Similarly, regions with seismic design provisions in their building codes experience less damage from earthquakes compared to areas with less stringent regulations. These examples demonstrate the cause-and-effect relationship between robust building codes and reduced disaster impacts. The absence of stringent building codes, often driven by the misconception of minimal risk or the pursuit of lower construction costs, can exacerbate the consequences of natural hazards. The devastation witnessed in areas with inadequate building codes underscores the critical role of these regulations in protecting communities.

The practical significance of this understanding lies in the recognition that building codes are not merely bureaucratic requirements but essential life-saving measures. Investing in structures designed to withstand local hazards represents a proactive investment in community resilience. This proactive approach, acknowledging inherent risks and mitigating their impact through robust construction practices, is far more effective than seeking an illusory disaster-free location. Stringent building codes, coupled with other mitigation measures like land-use planning and early warning systems, form a comprehensive strategy for reducing vulnerability to natural hazards. The ongoing development and enforcement of building codes, reflecting evolving understanding of hazard risks and construction techniques, remain crucial for safeguarding communities in the face of inevitable natural events.

6. Insurance is essential.

The essentiality of insurance directly contradicts the notion of a disaster-free state. Given that no location is entirely immune to natural hazards, insurance serves as a critical financial safety net for individuals and communities. Recognizing the inherent risk of natural events underscores the importance of insurance coverage in mitigating the financial consequences of disasters. This proactive approach, focusing on financial recovery rather than seeking a risk-free location, highlights the practical significance of insurance in navigating the aftermath of natural disasters.

- Protection against Financial Loss:

Insurance provides crucial financial protection against losses incurred due to natural disasters. Homeowners insurance, for example, can cover damages from events like hurricanes, wildfires, and certain types of flooding. Without insurance, individuals and families bear the full financial burden of rebuilding and replacing damaged property, potentially leading to devastating economic consequences. Real-world examples abound of individuals who, due to a lack of insurance, faced financial ruin after their homes were destroyed by natural disasters. These cases underscore the crucial protective role of insurance in mitigating the economic impact of these events, regardless of the perceived safety of a particular state. The belief in a disaster-free state can lead to a false sense of security, resulting in inadequate insurance coverage and heightened vulnerability to financial hardship in the aftermath of a disaster.

- Facilitating Recovery and Rebuilding:

Insurance plays a vital role in facilitating recovery and rebuilding efforts after a disaster. Insurance payouts provide the necessary financial resources for individuals and communities to repair damaged homes, businesses, and infrastructure. This injection of capital into the affected area accelerates the recovery process, stimulates economic activity, and helps restore normalcy. Following major disasters, insurance payouts often serve as the primary source of funding for rebuilding efforts. Communities with higher insurance penetration rates typically experience faster and more complete recoveries compared to areas with lower insurance coverage. This difference highlights the critical role of insurance in facilitating post-disaster recovery, regardless of the specific hazards a state might face. The misconception of a disaster-free state can hinder the adoption of comprehensive insurance coverage, potentially impeding recovery efforts when a disaster eventually strikes.

- Business Continuity:

Business interruption insurance is essential for mitigating the economic impact of disasters on businesses. This type of coverage helps businesses cover ongoing expenses and lost revenue during periods of closure or disruption caused by a natural event. Without business interruption insurance, businesses face significant financial challenges during the recovery period, potentially leading to permanent closure. Following Hurricane Katrina, many businesses with business interruption insurance were able to resume operations more quickly than those without coverage, demonstrating the importance of this protection in ensuring business continuity. The belief in a disaster-free state can lead to a false sense of security among business owners, resulting in inadequate insurance coverage and heightened vulnerability to economic hardship in the aftermath of a disaster.

- Community Resilience:

Widespread insurance coverage enhances overall community resilience in the face of natural disasters. When a significant portion of a community has insurance, the collective financial resources available for recovery are substantially greater, enabling a faster and more comprehensive rebuilding process. This collective financial strength reduces the overall economic impact of the disaster on the community and contributes to a more rapid return to normalcy. Communities with higher insurance penetration rates typically demonstrate greater resilience in the aftermath of natural disasters compared to areas with lower coverage. This difference underscores the importance of insurance in fostering community-level resilience, regardless of specific regional risks. The misconception of a disaster-free state can undermine the importance of comprehensive insurance coverage, potentially weakening a community’s ability to recover effectively from a disaster.

These facets of insurance highlight its crucial role in mitigating the financial consequences of natural disasters. Rather than seeking a hypothetical disaster-free location, recognizing the importance of insurance acknowledges inherent risk and emphasizes financial preparedness. This proactive approach, focusing on securing adequate insurance coverage, is far more effective than relying on the illusory promise of a risk-free environment. Comprehensive insurance, coupled with other preparedness and mitigation measures, forms a robust strategy for reducing vulnerability and enhancing resilience in the face of inevitable natural events. The misconception of a disaster-free state can lead to a false sense of security, hindering the adoption of comprehensive insurance coverage and increasing overall financial vulnerability when a disaster eventually occurs. Insurance, therefore, serves as a critical financial safety net, essential for individuals, businesses, and communities seeking to navigate the aftermath of natural disasters and rebuild their lives and livelihoods.

Frequently Asked Questions about Natural Disaster Risks

This section addresses common misconceptions regarding the existence of disaster-free locations and provides factual information about natural hazard risks.

Question 1: Is there any state completely immune to natural disasters?

No. Every state in the United States is susceptible to at least some type of natural hazard, whether it’s severe storms, floods, wildfires, earthquakes, or other potential dangers. The idea of a completely safe state is a misconception.

Question 2: Which states have the lowest risk of natural disasters?

Claims of states with the “lowest risk” are often misleading. Risk assessments depend on the specific hazard considered. A state with low earthquake risk might still be prone to severe storms or flooding. It’s essential to consider all potential hazards when assessing risk.

Question 3: If a state hasn’t experienced a specific disaster recently, does that mean it’s safe?

No. Infrequent occurrences do not equate to absence of risk. A long period without a specific event can sometimes create a false sense of security, leading to inadequate preparedness when an event eventually occurs. Historical data, while informative, does not guarantee future safety.

Question 4: How can one accurately assess natural hazard risks for a specific location?

Consult official sources like the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Weather Service, and state geological surveys. These agencies provide detailed information on regional hazards, historical data, and risk assessments. Relying on anecdotal evidence or informal sources can lead to inaccurate and potentially dangerous conclusions.

Question 5: Does living in a perceived “low-risk” area mean preparedness is less important?

No. Preparedness is crucial regardless of location. While some areas experience certain hazards less frequently, unforeseen events can occur anywhere. Complacency based on perceived low risk can have severe consequences. Proactive preparedness is essential for mitigating the impact of any potential hazard.

Question 6: If no place is entirely safe, what’s the point of preparedness?

Preparedness significantly reduces vulnerability and enhances resilience in the face of natural events. While eliminating risk entirely is impossible, preparedness empowers individuals and communities to minimize potential damage, protect lives and property, and recover more effectively. Proactive planning and informed decision-making are key to enhancing safety and resilience.

Understanding that no state is entirely free from natural hazards is crucial for effective preparedness and mitigation. Focusing on assessing and mitigating the specific risks present in any given location is far more effective than seeking an illusory risk-free area.

The following section will explore specific case studies demonstrating the impact of natural disasters on different regions of the United States.

Conclusion

Exploration of the question “what state has no natural disasters” reveals a crucial understanding: no location is entirely immune to the forces of nature. While relative risk varies geographically, every region faces potential threats, whether geological, meteorological, or hydrological. The misconception of a disaster-free state underscores the critical importance of preparedness, mitigation, and informed decision-making. Building codes, land-use planning, insurance coverage, and early warning systems are essential tools for minimizing vulnerability and enhancing resilience. Recognizing inherent risk, rather than seeking an illusory safe haven, empowers communities to take proactive steps toward safeguarding lives and property.

The pursuit of a disaster-free state is a futile endeavor. A more productive approach focuses on understanding and addressing the specific hazards present in any given location. Investing in resilient infrastructure, developing comprehensive emergency plans, and fostering a culture of preparedness are crucial for navigating the inevitable challenges posed by natural events. Ultimately, acknowledging inherent risk and embracing proactive mitigation strategies offer the most effective path toward building safer and more resilient communities, regardless of geographic location.